China’s Local Government Debt Crisis: Though Heavily Leveraged And Linked To Shadow Banks, Provincial Infrastructure Spending Will Come Just Short Of A Hard Landing

Sichuan Province in Southwest China is no stranger to ambitious infrastructure projects. Since 2009, the province has spent more than 5.6 trillion yuan ($920 billion) on new roads and transportation improvements.

However, last week, when Sichuan officials disclosed plans to earmark up to 4.3 trillion yuan on three highways, five railroads and what would be the largest airport in West China over the next two years, it was anything but business as usual. That scale of investment is nearly double Sichuan’s GDP last year and about 10 times its fiscal revenue during the same period. It’s even higher than the 4 trillion yuan stimulus plan the central government rolled out at the height of the 2008 financial crisis.

Sichuan is far from the only Chinese regional and local government to freely ramp up debt to stimulate growth. Jiangsu Province, north of Shanghai, has been on a spending spree since 2009 and is China’s most indebted local government, with about 770.6 billion yuan in outstanding loans, according to Chinese experts. And while the total debt of Chinese local governments is not known, even by the central government, economists have offered numbers ranging from 15 trillion yuan to 30 trillion yuan, which equals nearly 30 percent to 60 percent of the nation’s GDP. By contrast, U.S. state and local government debt stands at $3 trillion, or about 18 percent of GDP.

China has become so concerned about spiraling local loans and the quality of these loans that in late July, the central government urgently requested the National Audit Office to stop other work and produce a definitive report on local government debt. China watchers expect the results to be published in the coming weeks, probably before a plenary session of the Communist Party Central Committee in November, at which more details of China’s broad economic overhaul are likely to be revealed.

“The central government has an interest in getting an accurate figure” since they’ll be on the hook for a significant portion of that debt if it goes bad, said Robert King, senior economist at the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center in Mt. Kisco, N.Y. “Whether they also have an interest in reporting an accurate figure, we don’t know.”

Precise numbers are essential to gauge the health of local economies, which, if found to be unsound, would pose a clear risk to China’s future growth. On its own, Jiangsu would be the 16th-largest economy in the world, with a gross domestic product greater than Indonesia's. The GDP of other Chinese provinces ranks alongside countries such as Turkey, the Netherlands and Saudi Arabia. A Detroit-style default would have far-reaching effects.

“The dilemma Beijing is facing is that it needs infrastructure investments to support short-term growth, but by doing so, it is building up these debt problems in the country that is going to be big trouble in the long term,” King said.

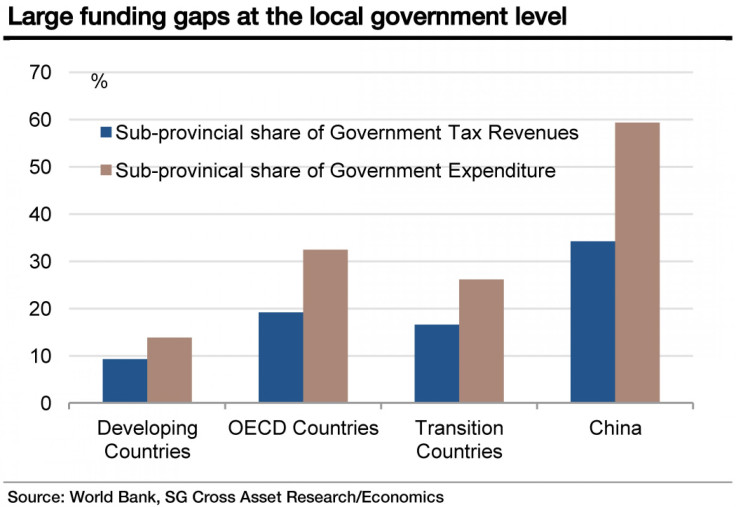

In the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008, external demand for Chinese products declined sharply, and net exports ceased to be a driving force for the economy. The government responded by engineering a monetary stimulus, but it placed the task of infrastructure spending squarely on local governments, which shoulder 90 percent of these expenditures. Between 2008 and 2012, net exports declined from 8 percent of GDP to negative 2 percent, while investment in China rose from 43 percent to almost 50 percent -- the highest in the world, and far higher than the figure in Japan or Korea during their catch-up spurts in decades past. After stabilizing in 2011, local debt surged again last year as policymakers launched a new wave of infrastructure spending to boost the Chinese economy amid its slowest growth in 13 years.

And while the financing burden for infrastructure has fallen on regional governments, the provinces and municipalities have not been allowed to borrow money directly or run a budget deficit since 1994, when Beijing introduced a ban due to concerns that local authorities were building up huge debts they could not repay. To get around this prohibition, provincial officials have turned to local-government financing vehicles, or LGFVs. These are state-owned companies that raise funds primarily via bank loans or bonds and have been the conduit for “most of China’s infrastructure investment since 2009,” Nomura's chief China economist Zhiwei Zhang said.

Local-government financing vehicles often raise cash through shadow banks, which conduct business “under the table” and avoid capital leverage regulations and requirements. China’s shadow banking system is responsible for a loan portfolio that amounts to more than a third of the debt issued by traditional banks and nearly half of the country’s GDP, up from just 25 percent five years ago, according to Societe Generale's estimate.

“The root cause of the problems associated with local government debt and shadow banking is the fact that a financial system dominated by banks can no longer cope with the demands of financing rapid urbanization,” said HSBC's chief economist for China, Qu Hongbin.

Beijing and Chinese observers are concerned that many LGFV loans obtained in 2008-09 were poorly collateralized and cash flow estimates were overstated. Local infrastructure projects often take years to generate investment returns, raising the possibility of default.

Moreover, higher funding costs and shorter debt duration, partly owing to the shadow banking system, have increased loan servicing fees, accelerating the risk in China’s debt accumulation. Weaker localities that must resort to shadow-banking finance often pay more than 10 percent in annual interest rates.

“Funding infrastructure projects with 10 percent-per-year interest rates and less than two years maturity looks dangerously like a Ponzi scheme for GDP creation,” said Societe Generale's Wei Yao.

The Systematic Risk Of LGFV Debt Is Rising

The recent downgrades of LGFV credit ratings are a sign of problems ahead. Although they were a rare occurrence in the past, so far this year there have been seven LGFV ratings downgrades, according to Nomura. These downgrades will lead to higher financing costs, making it more difficult for LGFVs to sustain their debt.

Financial statements released by LGFVs that sought capital from the bond market reveal a sea of negative cash flow. For example, Tianjing Urban Construction Company, the largest LGFV in China, reported that its cash flow in 2011 went deeper into the red, from 7 billion yuan in 2010 to 31 billion yuan.

Nomura estimates that without local government support to LGFVs, more than half of LGFV debt would have been at risk of default in 2012. In the case of a liquidity crisis, that number could easily go up to 70 percent.

However, the ability of local governments to fund LGFVs could be in jeopardy, said Nomura’s Zhang, under these possible crisis scenarios: A repeat and prolonged liquidity squeeze as occurred in June; a re-pricing of credit risks in LGFV debt because of defaults, which, in turn, would constrain new debt issuance; or a decline in property prices, bringing down the value of local land sales and reducing local revenue.

The practice of “capital injections” is pervasive in the LGFV sector, as the vehicles need to maintain a reasonable debt-to-asset ratio in order to borrow from banks and issue new debt. Because of local government support, there was a 4.2-percentage-point decline, on average, in the LGFV leverage ratio from 2010 to 2012, according to a report released by China’s National Audit Office. In extreme cases, LGFV solvency was only maintained thanks to these capital injections.

The NAO study also noted that “among 223 LGFVs audited by the NAO, 94 of them have assets that cannot be liquidated, which account for 37.6 percent of their total assets.” Official data show that LGFVs account for 14.7 percent of outstanding bank loans.

But ... Don’t Panic: No Imminent Crisis

A widely held view is that China will not slip into a full-blown financial crisis so long as the national government is willing to foot the bill for local government lending.

“Beijing can afford it. If Beijing [starts] leaving these local governments and these crazy financing vehicles they’ve created out to their own defenses, that when things become scary,” said Levy Forecasting’s King said. “But that’s unlikely.”

China has a very low debt-to-GDP ratio of 21 percent, and it has cash savings at the People’s Bank of China equivalent to 6 percent of GDP. Almost all government debt is denominated in yuan and owned by domestic entities, meaning that the central bank can prevent a government debt crisis with its unlimited liquidity capabilities.

China also has a huge amount of national savings, with $3.5 trillion in foreign exchange reserves, a 20 percent reserve requirement ratio and only a 65 percent loan-to-deposit ratio, indicating that there is plenty of room for the central bank to support the government in an emergency.

By comparison, the U.S. has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 73 percent; Americans are spenders, not savers (with a personal savings rate hovering around 3 percent); and $148 billion in foreign exchange reserves.

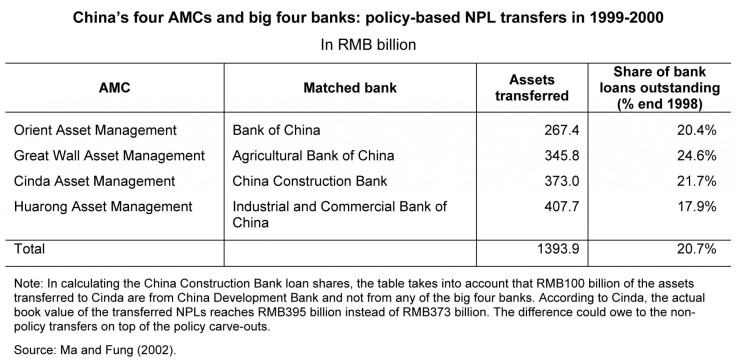

China has had experience with cleaning up bad debts before without much impact on its economy. The last time around, in the1990s, China sought to reform its biggest banks and take them public as part of an effort to modernize its financial system. So the country created four “bad banks” -- state-backed asset management companies (AMCs) created to buy $1.4 trillion worth of toxic assets accumulated by the nation's Big Four financial institutions during an earlier lending spree.

The amount of distressed assets held by the big banks -- Agricultural Bank Of China Limited (HKG: 1288), Bank of China (HKG: 3988), China Construction Bank Corporation (HKG: 0939) and Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (HKG: 1398) -- was equivalent to about 20 percent of their combined loan books, or 18 percent of China’s gross domestic product in 1998, according to a 2003 Bank for International Settlements paper.

These AMCs -- China Cinda Asset Management Co., Huarong Asset Management Corp., China Orient Asset Management Corp. and China Great Wall Asset Management Corp. -- could step in and bail out local governments if necessary.

The Hope For Change

On Sept. 11, Premier Li Keqiang said that China is taking “targeted measures” to address the issue of local-government debt that “people are all concerned about.”

On the fiscal side, revenue-raising and expenditures by central and local governments need to be rebalanced, experts say. In the past 15 years, the local government spent 90 percent of national fiscal revenue while the central government spent only about 10 percent. By comparison, the average ratio for central government spending was 46 percent in Organization for Economic Co-operation (OECD) countries.

“To arrest China’s rising government leverage … the new leaders should deleverage its local governments while leveraging up the central government and should try to replace local governments’ short-term bank and trust loans with longer-duration bonds,” said Bank of America Merrill Lynch economist Ting Lu.

Many reform advocates hope new policies announced during the party's Third Plenum this November will include aggressive expansion of a trial municipal bond program launched in 2011.

“We expect the government will gradually loosen the restriction and eventually allow municipal bond issuances, and it is possible that the new leaders will give some guidance during this meeting before the plan reaches the annual National People’s Congress meeting in March 2014 for legislative approval,” Lu said.

Currently, the local bond pilot remains tiny compared to the scale of local financing needs. The finance ministry in March set a quota of 350 billion yuan under the program for 2013. Only six localities -- Zhejiang Province, Guangdong Province, Shandong Province, Jiangsu Province and the cities of Shanghai and Shenzhen -- are allowed to issue bonds on their own.

Out Of The Shadows And Into The Light

The use of longer-term municipal bonds could relieve the troubling mismatch between infrastructure investments that may take decades to produce financial returns and the short-term loans that are often used to finance such projects.

However, economists warn that without acknowledging the debt problem and taking on some immediate pain, issuing debt directly to the public would become another new source of funding for local governments to keep their Ponzi scheme going. “There might be enough inflow of credit to wash over the bad debt for the time being, but it will make the hard landing further on worse,” King said. “Ultimately that debt doesn’t go away until someone acknowledges it via some form of default.”

Which could result in a bumpy ride for China’s economy, but at least it would avoid a costly and embarrassing full-blown crash of local governments.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.