CIA Terror War Torture And Rendition Program: An Italian Spy Is Sentenced To Jail - Can Tenet, Rumsfeld, Cheney, Ashcroft Be Next?

Nicolo Pollari, former chief of the Italian military intelligence agency SISMI, does not fit the stereotypical profile of a spy. He is a father of two girls and a former professor of tax and economics. He wears glasses and well-cut suits; his dark hair is tinged with gray at the temples.

He doesn't look like a convicted felon either. But Pollari was sentenced this month for his cooperation in the 2003 abduction and rendition of Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr, a Muslim cleric and then-resident of Milan.

The American CIA -- not SISMI -- was the primary player in the kidnapping. But that won’t save Pollari from a decade behind bars, unless he mounts a successful appeal.

An additional 23 Americans, including former CIA Milan station chief Robert Lady, were convicted by the Italian court in absentia in 2009. It was first court decision ever to challenge the U.S. practice of extraordinary rendition: abducting suspects without trial and sending them to foreign countries where they are likely to be tortured. But the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama worked with then-Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi to suppress the court’s request for extradition.

If such a conviction were actually enforced in the United States, it would be absolutely monumental. Imagine George Tenet, head of the Central Intelligence Agency at the time of Nasr’s abduction, being thrown into prison -- or any other of the high level officials who have been linked to the oversight of alleged abuses during the war on terror, like former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld or former Attorney General John Ashcroft.

It’s difficult to envision, because it probably won’t happen -- at least not anytime soon.

“In this country, which is the prime perpetrator of torture and human rights abuses in the war on terror, no steps have been taken,” Steven Watt, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU's Human Rights Program, said. “That is in marked contrast to what’s happening in Europe; they’re taking steps toward accountability,” pointing to charges filed against officials in Poland, Lithuania and Spain, among others.

Whether this constitutes a failure of the American judiciary system is a matter of heated debate.

A Suspect, Spirited Away

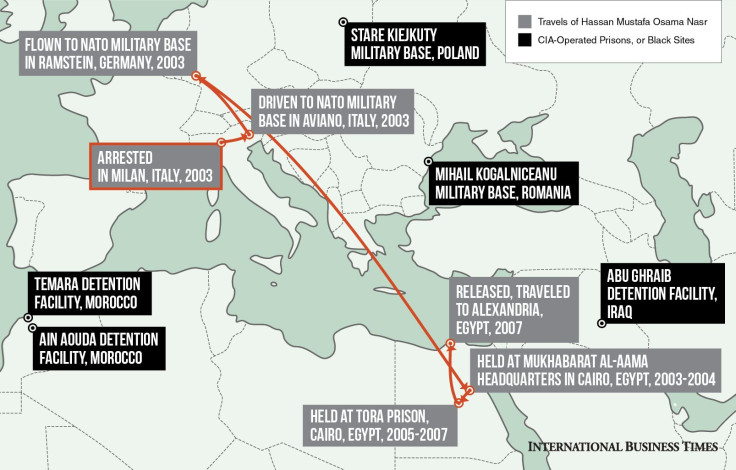

Nasr was walking down a quiet street in Milan on a February afternoon when he was suddenly abducted by strangers and thrown into a white van. According to his own testimony, Nasr was blindfolded, beaten and flown via Germany to Egypt, his home country, where he was tortured for seven months and held for a total of four years without trial.

Nasr had regularly criticized the United States, as well as the American-allied Egyptian administration of Hosni Mubarak. He was suspected of having links to al Qaeda. Before his 2003 rendition, U.S. intelligence officials had been working with Italian secret police to keep tabs on Nasr. But the abduction itself was an American undertaking -- later reports indicated that some Italian security forces were angry when they discovered that Nasr, against whom they had been building a criminal case, had suddenly been spirited away by the CIA. Pollari was apparently in on the deal, as were the four other Italian intelligence agents who were also sentenced, albeit to shorter prison terms.

As for Nasr, after years of detention in Egypt, whatever charges he faced have been dropped. The Italian courts have ruled that he will receive €1 million ($1.32 million) in damages.

Extraordinary renditions like these are just one of many questionable tactics the United States has employed against suspects during the war on terror. Other renditions made use of secret prisons operated by the CIA in various countries, including Iraq, Morocco and Romania. Then-President George W. Bush admitted to these so-called black sites in 2006 but asserted that no torture was carried out there.

Upon taking office, Obama shut down the extraordinary rendition program and condemned some of the Bush administration’s most controversial strategies. But he also approved surreptitious monitoring, ramped up targeted killings and resisted efforts to hold American officials accountable for the alleged war crimes of years past.

What Is The Meaning Of War?

Robert Turner, the associate director of the Center for National Security Law at the University of Virginia, argues that the CIA officials may well have been operating within their rights when they orchestrated the seizure of Nasr.

Turner, who has served in both the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government in national security advisory roles, explained that in the days following the Sept. 11 attacks of 2001, “the United States Congress -- with but a single 'nay' vote -- passed a law pursuant to the 1973 War Powers Resolution expressly authorizing the president ‘to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001.’ Seizing a member of a terrorist organization working with al Qaeda and located in a foreign country would clearly fall within this authorization, as would simply killing that individual.”

Indeed, if the war on terror is deemed an ‘armed conflict’ according to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, then the United States does have the right to kill or detain combatants without trial.

But the global manhunt for al Qaeda operatives is not a simple ground war, especially since it spans far beyond Afghanistan and into places like Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan. In order to justify operations like detention and targeted killings within an existing legal framework, U.S. officials had to prove that the war on terror constituted a legitimate armed conflict as defined by international treaties.

In short, Washington needed a new lexicon to describe its anti-terrorism efforts. And over the years, one phrase in particular has come into fashion: noninternational armed conflict.

But according to some critics, that designation is meaningless.

“That’s the interpretation the Obama and Bush administrations have put on the U.S. situation in the world, but there is, in fact, no international law support for that characterization,” Mary Ellen O’Connell, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame whose research focuses on international laws regarding the use of force, said.

“Armed conflict is the situation of armed groups engaged in intense armed fighting, and that is only happening for U.S. forces in one place: Afghanistan. And that is coming to an end. So the idea of a global armed conflict against terror is a legal fiction they have created in order to provide some cover for targeted killings and detention without trial.”

She adds that certain activities, including some allegedly carried out by some American intelligence operatives, are illegal no matter how you define wartime.

“Even in an armed conflict, you can’t detain someone secretly, you can’t torture someone, and there are limits on whom you may kill.”

A Judge Without A Gavel

Given the complexities involved in reconciling international and domestic laws, the extent of U.S. culpability for the abuse of suspected terrorists is up for debate. Some of these arguments fall into the realm of the U.S. judiciary system, which ostensibly has the power to investigate accusations of war crimes and human rights violations committed by U.S. officials.

In the Italian case, one magistrate named Armando Spataro showed considerable bravery in going after top intelligence officials in his own country -- a testament to the fierce independence of the Italian judiciary system, at least in that instance.

But in the United States, the administration has rendered federal courts toothless in matters related to the war on terror.

“There’s been a combination of arguments they’ve advanced that have been accepted, by and large, by the courts,” Watt said. “First, there was the state secret privilege, which says that any discussion of these issues in a federal court will undermine national security interests. In other cases, they have claimed qualified immunity, which basically meant that the U.S. officials involved in torture could not be tried in courts. And courts have been unable to grapple with the merits of some cases, because they’ve been dismissed on procedural grounds.”

For those seeking accountability for, or even official acknowledgement of, alleged human rights abuses committed against interrogation suspects, the bad news came in August of last year when U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder wrapped up a three-year Justice Department probe to investigate whether CIA interrogation techniques had crossed the line of legality. No charges were filed.

In a statement, Holder did not assert that no crimes had been committed. He only argued that “the admissible evidence wouldn't be sufficient to obtain and sustain a conviction beyond a reasonable doubt.”

This essentially closed the door on criminal investigations of U.S. officials.

“In addition to criminal prosecutions, there have also been attempts to bring civil lawsuits,” Watt said. “The response to those suits, under the Bush administration and now the Obama administration, has been to torpedo accountability efforts.”

Watt served as plaintiffs’ counsel on one of the most significant civil cases regarding U.S. accountability since the war on terror began. On behalf of five alleged torture victims, the ACLU filed to sue a company called Jeppesen Data Plan Incorporated, a subsidiary of The Boeing Company (NYSE:BA), for its role in helping the U.S. government transport terrorism suspects to countries where they were subjected to torture.

The case began in 2007 but was shot down for good in September of 2010, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit narrowly dismissed it on the basis of the state secrets privilege -- in other words, the case could not be heard at all because of the security risks associated with exposing sensitive information. The ACLU petitioned the Supreme Court to review that decision but was turned down May of 2011.

“Still today, no high-level officer has been held accountable for torture or for creating the architecture under which torture took place,” Watt said. “The only prosecutions for torture have been of some low-ranking soldiers -- that has been the only accountability in this country so far.”

Pointing Fingers

If the victims of alleged abuse at the hands of American officials ever manage to win their day in court, a major question remains: Whom exactly would be held accountable?

The potential for culpability goes all the way to the top. Both the White House and the Justice Department have authorized questionable CIA operations, including the establishment of secret prisons overseas and the use of enhanced interrogation tactics. All three government entities fall under the umbrella of the executive branch, and, in the years and months after Sept. 11, 2001, they worked together like a well-oiled machine: Directives came from the White House, legalities were debated by the Justice Department, and operations were carried out by the CIA.

In 2002, for instance, the CIA’s then-Deputy General Counsel John Rizzo asked the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, or OLC, for some guidance regarding the legality of using 10 particular methods of enhanced interrogation against Zubaydah, a high-ranking member of al Qaeda. The methods included facial slaps, sleep deprivation, waterboarding and trapping Zubaydah -- who had a fear of bugs -- in a box with an insect.

The OLC lawyers granted their approval in a top secret memo, which was made public -- and its decisions nulled -- by the Obama administration in 2009.

Turner strongly disapproves of tactics like waterboarding and says the OLC decisions of 2002 were mistaken but argues that the cooperation between the CIA and the Justice Department constitutes a noteworthy attempt by intelligence officials to ensure the legality of their actions. For him, this is a case of good people doing bad things in the interest of protecting American lives, in the aftermath of the deadliest terrorist attacks ever carried out on U.S. soil.

“I do not blame the CIA or other elements of the intelligence community,” Turner said. “Indeed, I think it was admirable for John Rizzo to seek guidance from the OLC in the Department of Justice about drawing lines -- so that CIA interrogators and other personnel could gain the most intelligence without, in the process, violating the law. Nor, for that matter, do I favor prosecuting the Justice Department lawyers who, I believe, got the answers wrong.”

The 2002 OLC memo contains lengthy guidelines regarding the implementation of questionable interrogation methods; its signatories assert that the techniques should not cause severe pain or trauma. Clearly, intelligence officials and administration legal experts knew that they were walking a very fine line.

Assigning culpability becomes even more complicated when directives filter down through -- and are distorted by -- long chains of command. And in the cases that involve extraordinary rendition, torture is not carried out by American citizens but by foreign operatives. In the case of Nasr, Egyptian officials were behind most of the physical abuses.

“If U.S. government employees directly participated or encouraged inhumane treatment of any detainee, that was a violation of the law of armed conflict,” Turner explained. “But one would have to establish that the individuals who allegedly took part in the seizure of Mr. Nasr were aware that he would be abused in order to hold them accountable for subsequent abuse at the hands of Egyptian officials.”

Critics of the American rendition program argue that the CIA knew full well that its abductees would be treated inhumanely in certain countries, including Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

“Extraordinary rendition is a euphemism for kidnapping, arbitrary detention and torture; there are a number of human rights violations encompassed within extraordinary rendition,” Watt said. “Victims of these abuses have never even gotten official acknowledgement. They deserve their day in court.”

Justice: A Dish Best Served Cold?

When the war on terror began, America was reeling from an attack of unprecedented scale. Nearly 3,000 people in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania lost their lives on Sept. 11, 2001. So when U.S. officials promised to use every tool available to them to track down and punish those responsible, the American public was right there with them.

Since that day, the core leadership of al Qaeda has been decimated, due in large part to the highly controversial drone strikes favored by the Obama administration. Harsh interrogations may have also played some role in helping gain valuable intelligence, though this has been subject of intense debate.

So it is no surprise that calls for accountability often fall on deaf ears.

But judiciary wheels are turning, even if not in the United States. The American CIA officials convicted in Italian courts have been protected by Obama, but, according to O’Connell, they may be more vulnerable than they realize.

“I think the chances are not bad that one or more of the 23 will end up being extradited to Italy,” she said, explaining that one of the former operatives could make the mistake of traveling to a country that has no problem complying with Italy’s extradition request. “That will take a lot of political will or commitment to the rule of law by officials in Italy and everywhere else, but the odds on that are not as slim as people think.”

People at higher levels of government can probably rest easier, as any judicial inquiries into their activities could be delayed for decades -- or indefinitely. But critics of the war on terror argue that justice must be served, no matter how long it takes.

“There were violations of the law; that’s clear,” Watt said. “The question now is just accountability for the victims. I think that’s going to take some time, but it will happen. Without accountability, there’s a possibility that history will repeat itself.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.