Climate Change And Food Security: Water Scarcity Threatens Major Food Companies, But Few Are Tackling The Challenge

On California’s carrot farms, sprawling fields of orange and leafy-green vegetables are turning to a shriveled brown. Cattle are vanishing from Texas pastures, where grasses have given way to dirt and dust. Across the western U.S. and around the world, enduring drought in particular and water scarcity in general are straining the operations of major food companies.

Yet few of these businesses are confronting the problem, researchers say. While most companies acknowledge the lack of water poses a risk to their supply chains, only a handful are actively working to slash water consumption and protect the rivers and watersheds that sustain their fields and livestock.

“The business model of most food companies is premised on the assumption that water is limitless and cheap,” said Brooke Barton, the director of the water program at Ceres, an advocacy group for environmentally focused investors. “That should be alarming to investors.”

By many accounts, the water challenge will only get worse. Withdrawals of freshwater supplies have risen by at least 1 percent a year in the past three decades, and could rise by a staggering 55 percent in the next few decades, the United Nations water agency estimates. Driving this increase will be billions more people, accompanied by an expansion of agricultural, energy and manufacturing production to meet rising demand. Climate change will exacerbate and intensify the world’s droughts as it causes erratic weather patterns, making it harder to produce food in the same areas and in the same ways as farmers do today.

“For a lot of reasons, we’re coming to a tipping point in water supplies,” Barton said.

In a report released Thursday, Ceres studied 37 major U.S. and global food companies, including packaged-food firms such as General Mills Inc., beverage giants such as the Coca-Cola Co., meat producers such as Tyson Foods Inc. and agricultural outfits such as Chiquita Brands International Inc. Researchers found only 30 percent of the companies had set goals to cut water use in their operations. While most firms are evaluating water risks in office buildings and warehouses, about two-thirds are still not targeting their agricultural supply chains, where the vast majority of water is consumed for food production. Only six have sustainable-agriculture policies focused on water risks.

At the same time, these companies are seeing their profits squeezed and investments stymied because of water-related challenges.

The Campbell Soup Co.’s carrot division reported a 28 percent decline in profits in its fiscal second quarter ending Feb. 1, citing extreme weather in California. Agribusiness giant Cargill Inc. closed a beef-harvest facility in Milwaukee last year and said it would shutter a corn-milling feed facility in Tennessee this year after drought helped push the U.S. beef-cattle herd down to its lowest level in more than 60 years. In April, Coca-Cola scrapped plans for an $81 million bottling plant in southern India because of opposition by local farmers, who feared the facility would strain groundwater supplies.

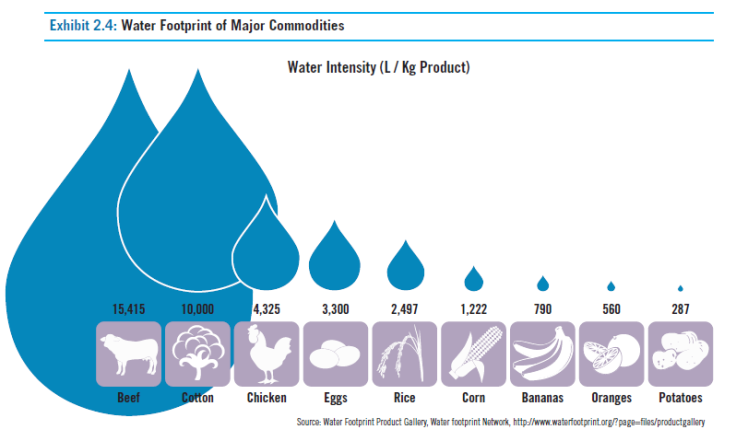

“Agriculture and food production as we know it in the United States is at risk, perhaps at far greater risk than we realize,” Jay Famiglietti, a senior water-cycle scientist at NASA and professor at the University of California at Irvine, said on a press call Thursday, when he noted 80 percent of the world’s freshwater supplies are used to produce food.

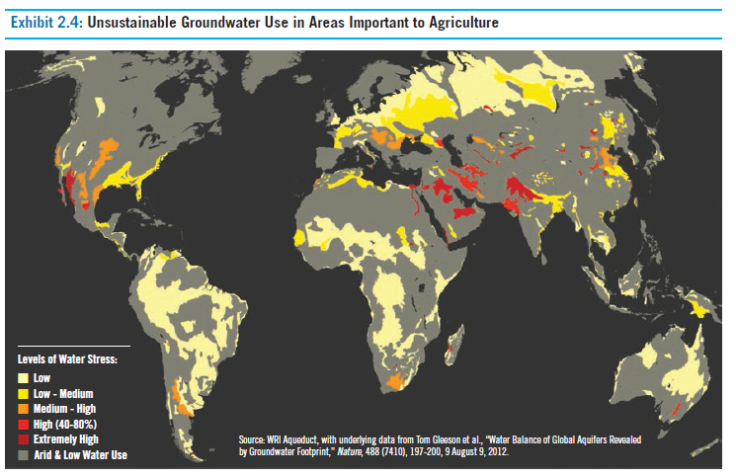

Amid California’s four-year drought, Famiglietti said, farmers are increasingly pumping groundwater to sustain crops and livestock. As a result, California’s groundwater supplies are quickly depleting, and the state has lost about 8 million acre-feet of groundwater since 2011. In the Colorado River basin in the U.S. Southwest and Ogallala Aquifer in its Midwest, groundwater is disappearing at a similarly rapid rate.

“This is largely tied to agricultural production,” Famiglietti said. “If we’re going to manage our way through our U.S. and global water crises, we need the food industry to step up and play a leading role as environmental stewards.”

In the Ceres report, researchers assigned the 37 food companies individual water-risk management scores, based on how the firms address water issues at a corporate level, in direct operations and across agricultural and manufacturing supply chains. On a scale of zero to 100, two companies earned just 1 point: Monster Brands, which makes highly caffeinated soft drinks, and Pinnacle Foods Inc., a packaged-food firm whose brands include Birds Eye frozen foods and Duncan Hines cake mixes. The low scores indicate the companies are hardly giving water a second thought, the report found.

Unilever PLC, the British-Dutch consumer-goods behemoth, earned the highest score of 70 points. The company has deeply evaluated the water risks of its direct operations and supply chains, and its code of conduct for agricultural producers defines rigorous standards for water use and pollution control. Unilever has previously estimated that natural disasters linked to climate change, including water scarcity and reduced food production, already cost the company about $400 million each year.

Jerry Lynch, General Mills’ chief sustainability officer, said tackling water risks is “a business imperative” for the maker of Cheerios cereal and Yoplait yogurt, which earned 57 points in the Ceres report. “We spend a lot of time thinking about and working on water.”

The Minneapolis company gets much of its dairy supply, almonds, berries and tomatoes from California, and General Mills has several processing facilities in that state. Lynch wouldn’t say how California’s drought crisis has affected the firm’s operations, explaining General Mills doesn’t comment on specific commodities. But in a 2014 response to the Carbon Disclosure Project, General Mills said it was a large buyer of U.S. wheat and noted, “If water becomes scarcer, it will likely cost more to obtain ingredients such as wheat grown in this region.”

General Mills hired the Nature Conservancy in 2012 to evaluate the 85 watersheds that sustain the company’s operations and food production around the world, including the San Joaquin and Los Angeles rivers in California. The group identified eight watersheds where scarcity and pollution pose the biggest long-term threats to agriculture. They include the Irapuato region in Mexico, where farmers grow broccoli and cauliflower for General Mills’ Green Giant frozen-food brand.

Lynch said the team found the Mexican watershed could become “inoperable” within two decades as water supplies dry up or become polluted due to overuse and climate conditions. “Twenty years is a very real time horizon,” he said. To help protect the watershed, General Mills provides interest-free loans to its vegetable growers to help them adopt drip-irrigation technology, a more-efficient way to water crops. The company estimates the irrigation initiative has already helped save about 1.1 billion gallons of water a year.

Barton of Ceres said the organization’s water-risk report is designed to help investors understand how climate change and water scarcity could affect the returns of their investment portfolios. “Our motivation is to help the investor understand which companies are best positioned to navigate the scarcer waters of agricultural production” and which companies run the risk of losing profits and assets due to inefficient water use, she said. “We’re at a moment where companies have to really value every drop.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.