Colorado Mine Spill 2015: Thousands Of Abandoned Mines Threaten US Rivers Amid Slow Cleanup Efforts

The western United States is pockmarked by hundreds of thousands of abandoned mines like the Gold King site in Colorado, which spewed yellow-tinted toxic sludge into the Animas River this month. The nation’s early rush to dig gold and minerals, combined with decades of lax regulations, has left a massive, lingering mess that state and federal officials say they’re still fighting to clean up.

The open sores on America’s landscape are tainting the soil and groundwater supplies in the western states, destroying river and desert ecosystems and exposing millions of residents to arsenic, lead and other health-harming materials, environmental experts say. Yet agencies estimate it could take decades before these abandoned mines -- some more than a century old -- are safely shuttered. Until then, disasters like the Animas River spill, which dumped 3 million gallons of wastewater on Aug. 5, could strike again.

“The longer you wait to deal with the problem, the more you’re going to have these failures and these spills occurring,” said Ron Cohen, a civil and environmental engineering professor at the Colorado School of Mines in the city of Golden. “And they’re going to happen more frequently as the years go by.”

Roughly 500,000 abandoned hard-rock mines are scattered across the U.S., with most concentrated in the 12 western states, according to federal estimates. The numbers are rough, however. Officials are still tallying the actual number of inactive mines, which are often difficult for researchers to explore due to flooding, unstable ground or dangerous conditions. It's also possible to overestimate the number of abandoned mines; for instance, two surface openings that connect to the same underground tunnel system may be counted as two separate mines.

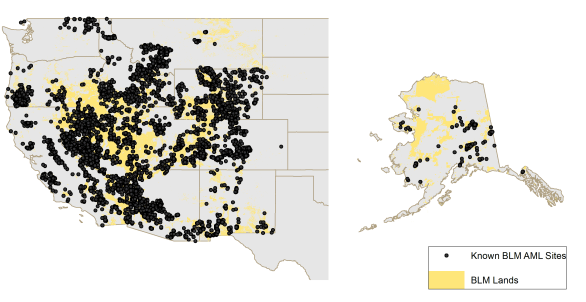

The U.S. Geological Survey is building a database that will identify abandoned mines, including specific features like shafts and open pits, but the information is not yet available for public access, geologist Peter Schweitzer said by email. The Bureau of Land Management, which oversees mines on public lands, has so far identified 48,100 abandoned sites within its jurisdiction. Around 80 percent of the sites still need further analysis or environmental cleanup efforts, according to the agency.

Abandoned mines can pose major threats to human health and the environment, although the scope of their risk depends heavily on the size, location and characteristics of each site. Dust containing arsenic, lead and radionuclides can blow from the mines and into surrounding communities. Heavy rains can wash away silt and debris from the mines, clogging waterways and flooding streets. And highly acidic water laced with metals can leak from sites for more than 100 years, polluting streams and contaminating fish habitats, harming people who drink the water or eat local fish.

Around 33,000 hard-rock mines have polluted local water sources or left behind piles of toxic “tailings,” the waste material created by processing ore to separate out metals. Mining activity across the board has contaminated about 40 percent of the streams connecting to watersheds in the West, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

For most of U.S. history, prospectors and mining companies seeking gold, silver, copper and lead simply abandoned their mines after extracting all the valuable minerals. In the early 20th century, state rules on closing mines or handling toxic tailing ponds were weak. Cohen said he spoke in the 1980s with miners who worked in Colorado around the time of World Wars I and II. “They told me the environmental disturbance was merely a byproduct, a side effect of helping develop the country,” Cohen said.

Those attitudes started to shift in the 1970s, when the federal government began cracking down on rampant air and water pollution nationwide. In 1997, Congress adopted a series of policies to reclaim “abandoned mine lands” under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act.

Undoing decades of widespread damage has proved an enormous task for the EPA, Bureau of Land Management and other federal agencies responsible for addressing the inactive hard-rock mines. The federal government spent at least $2.6 billion from 1997 to 2008 to reclaim the sites, and agencies estimate they spent roughly $85 million more every year in this arena.

But in order to clean the mines, agencies must first find where they are and establish what risks they pose. The Bureau of Land Management still hasn't taken an inventory of an estimated 93,000 abandoned hard-rock mines spread across public lands in California, Nevada and Utah. Validating those sites could cost the agency $212 million and take 20 years to complete, assuming the work is carried out by 10 two-person crews, the agency said in a November 2014 report.

The threat of leaks and spills from these sites is a growing problem as more people move out West, boosting the population’s overall exposure to contaminated water and polluted air. The Gold King Mine spill in Colorado was alarming not just for its size -- other spills in recent years have rivaled this one -- but for how close the brightly colored toxic sludge came to communities in Silverton and Durango and on the Navajo Nation reservation.

Cohen, the Colorado mine expert, said he hopes the alarm raised by this month’s disaster will spur federal and state officials to accelerate their mine cleanup efforts. “It may rekindle that focus,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.