On Columbine Shooting Anniversary, School Security Industry Continues Expanding Despite Challenges

The April 20, 1999, massacre at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, sparked a renewed gun control debate, flooded schools with police officers and inspired a wave of zero-tolerance discipline policies. As a result, one of the deadliest school shootings in American history launched the issue of school security into the national spotlight.

Seventeen years later, it's still there.

Every event so horrifying renews efforts by lawmakers, administrators and parents to keep their children safe — while also creating opportunities for businesses ready to help them do so. But the school security business has encountered several challenges as it has evolved over the past two decades. In part because it's spurred on by such emotional events, some experts argue the industry tends to focus too much on preventative equipment, active shooter scenarios and misguided teacher training programs that can leave schools vulnerable to other threats. Instead, they say, a balanced approach is needed to blend technology with threat assessment techniques and locally developed standards.

"The school security industry is now a million-dollar industry. A lot of people and a lot of organizations are using a very fear-based approach to market whatever they're selling," said Michael Dorn, the executive director of Safe Havens International, a campus safety nonprofit based in Macon, Georgia. "What we're seeing is an unprecedented amount of approaches that have never been tested, never been validated to work, but we're seeing people describe them as best practices and school districts rushing out to put them in place."

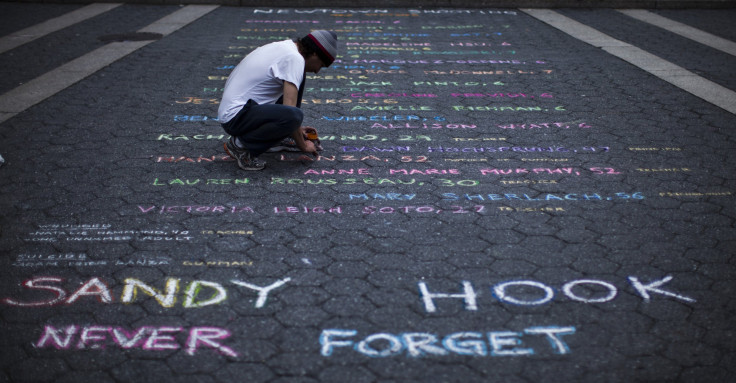

Columbine, where high schoolers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 13 people and then themselves, often serves as a primary reference point for school shootings. Some of the more infamous massacres often mentioned in the same breath include those at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia, in 2007; Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012; and Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon, last October.

The recurrence of these devastating incidents has led to fluctuations in the funding dedicated to protecting schools. After Columbine, the U.S. Justice Department spent more than $870 million on school resource officers, according to Mother Jones, and other government agencies provided $58 million in grants supporting mental health, the Wall Street Journal reported. After Sandy Hook, research analyst IHS released a study predicting that the market for school security system integration would reach $4.9 billion by 2017.

To be sure, a lot of the capital has created programs that work. For example, about 80 percent of colleges now have threat assessment teams, and a third of educators told the School Improvement Network in 2013 their schools now have better locks on their doors.

The urgency of addressing school security, however, also can provide an opportunity for companies to promote products and techniques that may not be schools' best options, said Ken Trump, president of the consulting firm National School Safety and Security Services in Cleveland. Whiteboard shields, backpack armor and even bulletproof underwear have cropped up in recent years.

"You have people who are maybe well-intended, but it's not their expertise, [selling these products]," Trump said. "While certainly any type of physical security is a supplement, it's not a substitute for a more comprehensive school safety program. It's not an issue of just fortifying your front entrance, it's what you have in place with those people beyond that entrance that is the most valuable asset in school safety."

David Muhlhausen, a criminal justice expert with the D.C.-based conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation, similarly noted that these items, while often helpful, aren't universally useful. "Not every school needs metal detectors," he added.

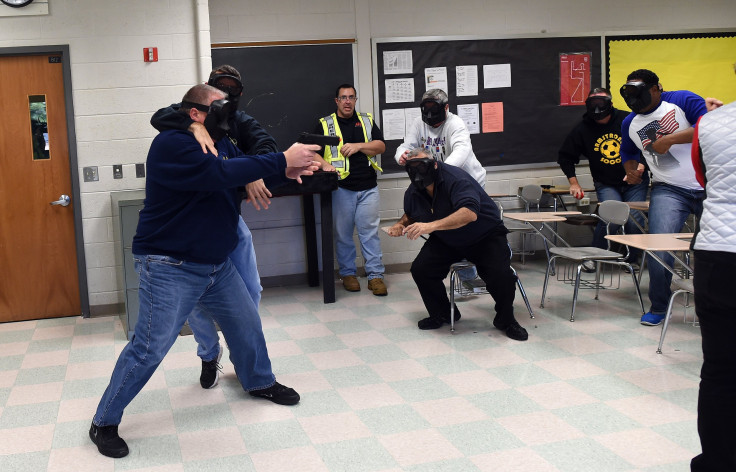

Muhlhausen said what schools do need is training on how to handle a variety of threats. But standards for how to achieve that can't come down from the federal government — they need to be locally developed.

They also should not focus too much on active shooter scenarios, said Safe Havens International's Dorn. About a quarter of the active shooter incidents between 2000 and 2013 took place at American schools, according to the FBI, but the percentage of youth homicides that occur at school is under 2 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Training for dangerous situations should be individualized based on the issues the schools face most frequently, Dorn said. For instance, a study by his organization estimated that about 525 people died in school bus accidents or other incidents with vehicles on school property between 1998 and 2012. By comparison, 62 were killed in active shooter incidents.

"We want to deal with all forms of death and serious injury, not just those that frighten us the most," he added.

Dorn gave an example about a client he once worked with in an old schoolhouse that didn't have air conditioning. In order to keep the classrooms cool, teachers would leave the doors open — a major security risk. In their case, the school didn't need tactics for fighting active shooters as much as it needed to fix its AC.

"If we're going to spend $10 million, let's make sure we're doing it in the wisest way," Dorn said.

Dewey Cornell, director of the Virginia Youth Violence Project at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, wrote in a commentary provided to International Business Times that he worried fears about school shootings had diverted attention and resources aimed at addressing students' mental health.

"The nationwide movement to increase school security seems to have displaced efforts to prevent school violence through psychological interventions," Cornell said in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry last year. "School systems that are spending millions to reinforce their building entrances, hire security staff and install electronic door locks and alarm systems nevertheless lack funds to hire enough counselors, psychologists and social workers to work with troubled students and carry out prevention programs."

In Chicago, teachers' union field representative John Kugler said active shooters physically in schools aren't as common as gang violence nearby. But he said he wasn't sure educators were being regularly trained on either threat. He hasn't been able to get documents from the district detailing its training methods.

"If the district isn't using their resources to do safety training, then what are they using their resources for?" Kugler said, adding that he wasn't aware of any sessions on terrorist threats or hostage situations, either.

If there's one state making moves on school security, it's Indiana, where Gov. Mike Pence signed Senate Bill 147 into law there last month. The bill turns over authority for setting school security standards to the state Department of Homeland Security and requires an emergency response system that transmits information to law enforcement during an active shooter situation, the Clarion News of Corydon reported.

Mason Wooldridge, co-founder of the Our Kids Deserve IT group that helped push the legislation through, said he hoped these factors would improve officers' response times and tactics once arriving on scene. He also said he wanted the state to establish building codes for constructing new schools, requiring things like "much better doors, glass that can't be penetrated [and] a camera system directly connected to the dispatch center."

Wooldridge also supported the remodel of Southwestern High School, which NBC's Today Show labeled "the safest school in America." Teachers at the Shelbyville, Indiana, school carry key fobs at all times that can alert police to a problem, and halls are equipped with smoke that can impede a suspect's vision, PRI reported.

Though he knows not all schools will be able to afford that, Wooldridge said he hopes the movement spreads to states like Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Florida.

"Let's not wish we had done something better in a few years," he said. "Let's do something now."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.