Column-Dollar May Rely On QE-freed Euro Bond Buyers: Mike Dolan

Plague, war and inflation define the year so far - but faith in the U.S. dollar seems to have made it through the first three months.

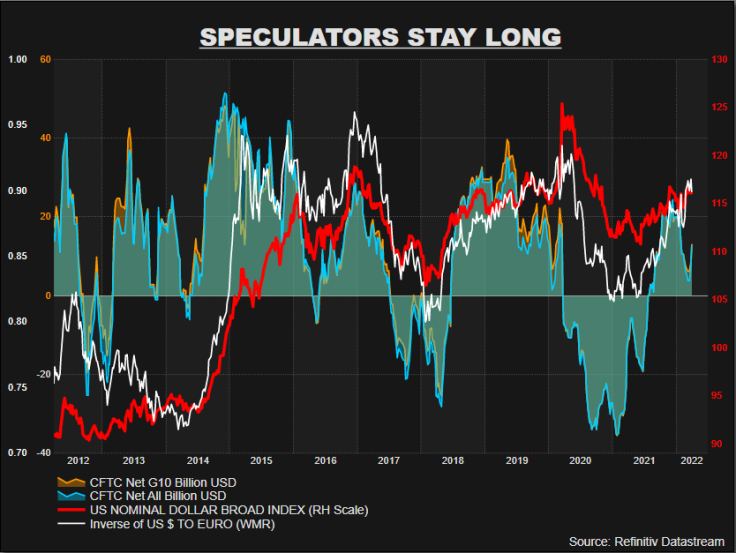

Thanks largely to a newly hawkish Federal Reserve and some yawning yield gaps in ferociously volatile bond markets, speculators have remained net long of dollars through the turbulent first quarter. It underscores an overwhelmingly bullish consensus for a stronger dollar among asset managers coming into 2022.

And yet positioning is as long on dollars at the end of the March as it was short on it exactly one year ago. And that bet went sour over the remainder of 2021 as the buck flew higher.

Is there a repeat performance in store? Will the dollar back off now that a Fed tightening cycle has begun and been priced? Have U.S. yields peaked already? Will peace break out in Ukraine and COVID-19 get consigned to the past?

There are more questions than answers as always - but a counterview to the consensus always catches the eye.

BNP Paribas' research team took a pace back from the frenetic news flow this month and sketched out a longer-term view of cross-border flows could spell trouble for the dollar ahead.

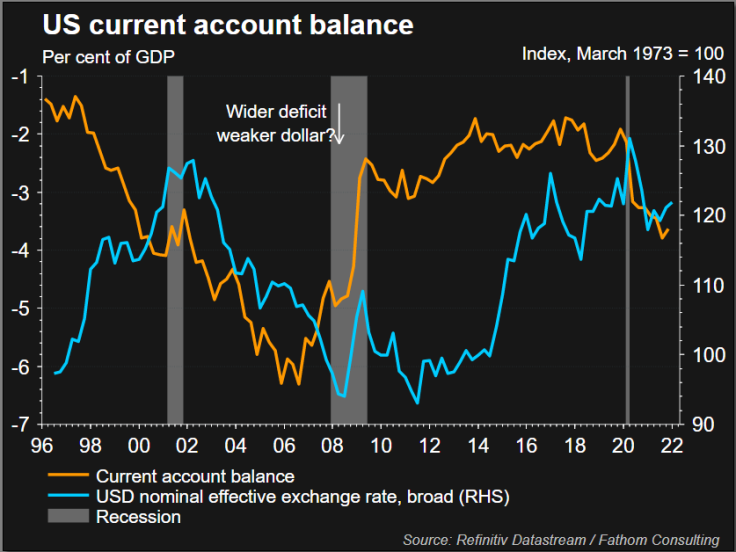

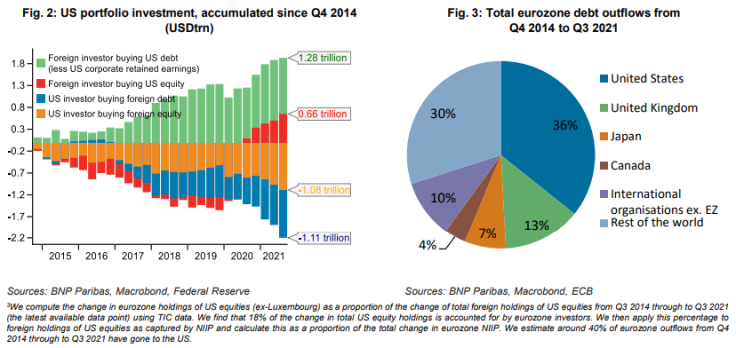

Examining investor, corporate and reserve manager behaviour, they showed that since 2014 a key funding source for the yawning U.S. current account deficit - which has almost doubled to 3.6% gross domestic product since 2020 - has been foreign buying of U.S. bonds by euro zone investors.

Japanese funds remain the largest single national holder of U.S. Treasuries, but inflows over the past eight years originated mostly from euro zone - 61% of the $1.69 trillion rise in foreign exposure to U.S. fixed income over that time.

The BNPP team argue that euro zone investors facing negative nominal yields at home over that period were drawn to unhedged dollar bond exposure. And those dynamics are now shifting.

The dollar's history of peaking when the Fed starts raising rates and the prospect of European Central Bank "normalising" policy later this year change the picture.

And winding down the ECB's bond buying, as much as any rate rises themselves, play a key part.

Their analysis outlined how negative supply of euro zone bonds net of redemptions and ECB bond buying leads to mechanical transfer of bonds to the central bank from private investors - who have then used the proceeds to invest in overseas assets.

But as the ECB pulls back from the market, they estimate there a net 174 billion of new euro zone bonds this year that will not hoovered up by the central bank - a positive net supply that brings us back to 2014 levels.

"But the FX market does not appear to price in this shift, which we think will support the euro," BNP Paribas told clients.

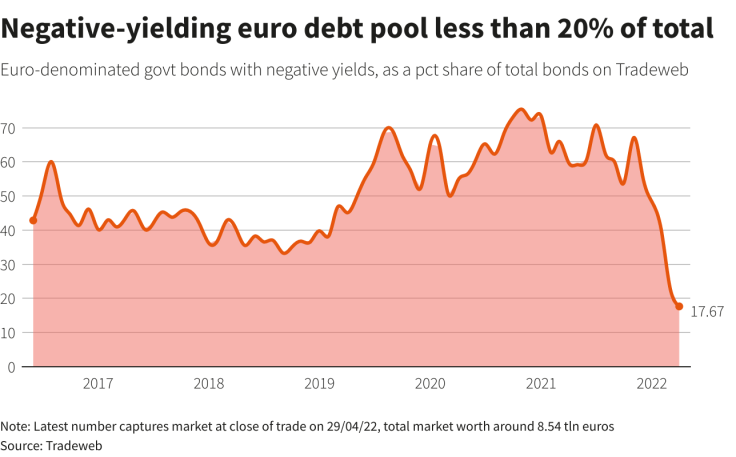

The return of positive yields on bonds that hold no currency risk for the euro zone's more conservative investors just underlines this. And euro bonds with positive yields now account for about 70% of all outstanding compared to less than 30% a year ago.

Graphic: CFTC data on speculative positioning on the dollar -

Graphic: US current account and the dollar -

PLAGUE, WAR AND INFLATION

There are other reasons to be more negative on the dollar of course - such as a preference for currencies in commodity exporting economies that will ride the surge in energy, raw materials and food prices.

Many investors are also now wary of some currency reserve managers diversifying away from dollars after G7 powers froze the overseas reserves of Russia's central bank in retaliation for the invasion of Ukraine.

Others think the Bank of Japan will eventually relent in its policy of capping long-term bond yields there - which pummelled the yen last month as the Fed tightened.

But long-term dollar bulls still seem confident.

Stephen Jen of hedge fund Eurizon SLJ thinks the three gloomy horsemen of 2022 - COVID, war and inflation - will still play out well for the dollar over the rest of the year.

"What is interesting to me is that China's number one challenge is Covid; the U.S. number one challenge is inflation; and Europe's number one challenge is Ukraine-Russia," he wrote.

Jen reckons the aggravated inflation picture will keep the Fed tightening through the year but also keep U.S. equities high as companies are able to pass on input prices in such a buoyant economy.

By contrast China's COVID-19 hit will drag harder on its economy and require more policy easing there, he thinks. And the euro area and ECB will be held back by the demand effects of a Ukraine-related energy shock that it will feel the hardest.

If that's all to plays out on the exchanges, the consensus will need to prove more durable than it did last year.

Graphic:BNP Paribas chart on capital flows -

Graphic:Euro zone negative-yielding debt pool shrinking fast Euro zone negative-yielding debt pool shrinking fast -

The author is editor-at-large for finance and markets at Reuters News. Any views expressed here are his own

(by Mike Dolan, Twitter: @reutersMikeD. Charts by TradeWeb, BNP Paribas and Fathom Consulting; editing by David Evans)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.