Column-Fed Hangs Tough As Wage Growth Gets Real Again: Mike Dolan

If markets are wondering why the Federal Reserve just won't play ball with their 'peak interest rate' pricing, the answer probably lies in the resumption of U.S. real wage growth.

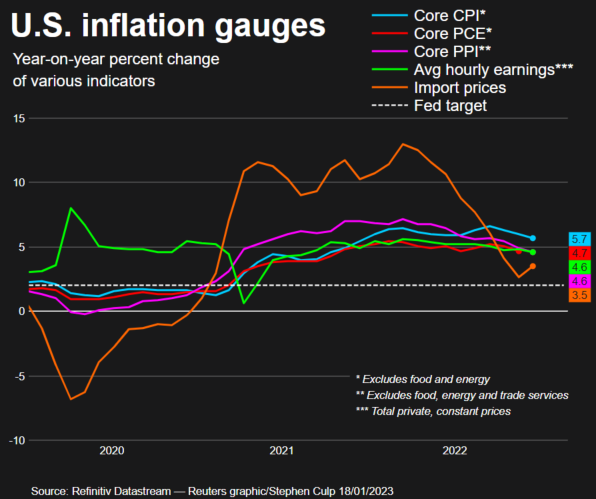

Investors were unnerved this week by Fed policymakers insisting the central bank would push on with plans to raise rates above 5% this year despite mounting evidence that disinflation has taken hold and the economy is stalling.

The Fedsters were merely sticking to their guns.

None seem to see a reason yet to change the collective indication from last month's policy meeting of a Fed 'terminal rate' around 5.25% by midyear - compared with today's 4.25-4.50% target.

Only last month, 10 out of 19 of the Fed's policy committee saw another 75 basis points of rate hikes while nine saw a full percentage point or more of additional tightening. Minutes of the meeting showed none expected to cut rates this year.

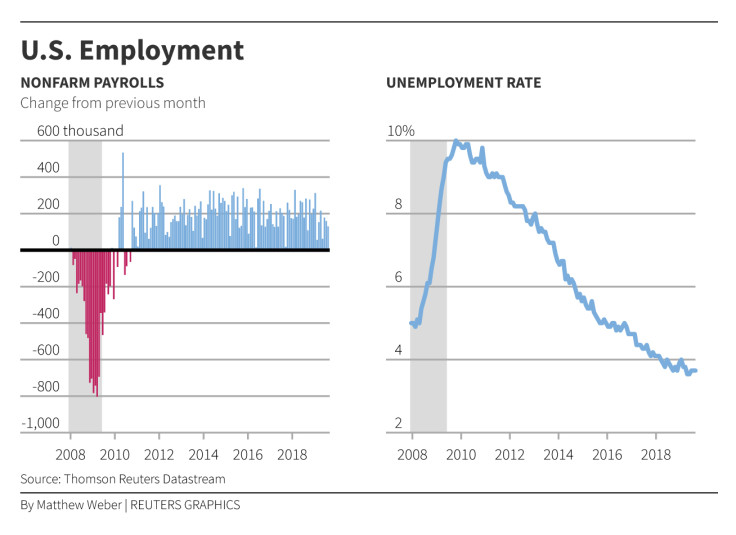

Even if consumer and producer price growth is now receding at last, the message is that inflation still remains far above the 2% target and U.S. labour markets are still way too tight if that goal is to be achieved.

The problem is that financial markets still don't believe them.

Futures pricing now sees Fed rates peaking as low as 4.88% before midyear and a half point of cuts by December. In short, markets think the Fed will blink once recession takes hold - almost regardless of inflation projections at that point.

The gap in perceptions is rooted less in runes of consumer price data than in the machinations of the jobs market, labour shortages and wage bargaining.

Dallas Fed chief Lorrie Logan, a voting Fed policymaker this year, fretted this week about service sector inflation driven by an "overheated" labor market. "The most important risk I see is that if we tighten too little," Logan said on Wednesday.

"Labor costs continue to grow more rapidly than is consistent with 2% inflation," Boston Fed's Susan Collins said on Thursday.

For many Fed watchers, the return of U.S. real wage growth after a bruising 18 months in the red is the crux of the matter and may ultimately define the Fed trajectory, the chance of a 'soft landing' for the economy and markets' outlook this year.

Brian Nick, chief investment strategist at giant U.S. asset manager Nuveen, points out that while nominal wage growth may be easing, it's not falling as fast as inflation. Year-on-year earnings growth in excess of 4% won't be seen by the central bank as consistent with a 2% inflation target, he said.

Even though real year-on-year wage growth still looks 'ugly' in negative territory, in part due to COVID-related income supports being dropped last year, annualised 6-month real disposable income growth - where monthly rates are extrapolated to show what a 12-month pace would be - has already turned positive.

"This is so crucial," said Nick, who began his career at the New York Fed. "It's going to keep the Fed on the hawkish side but it's also going to prevent the economy from falling into recession."

Graphic: Markets Don't Believe the Fed

Graphic: Nuveen chart on US real wage growth turning positive

Graphic: AXA chart on US real wage growth

'PRICE/WAGE RACE'

Nick said he saw another four Fed quarter-point rate rises to June, with the last of those particularly painful for risk assets if the market doesn't agree that it's necessary. And agrees that rate cuts won't start until 2024.

"Overall, that's a pretty good macro outcome - but not such a great market outcome," he said, adding that he only saw a one-in-three chance of recession but downwards revisions to corporate earnings.

HSBC's U.S. economist Ryan Wang also sees the possibility of a stubborn Fed. While sticking to a forecast for the terminal rate between 4.75-5.00%, he said "risks are skewed toward the FOMC eventually lifting the terminal rate a bit higher than our forecast."

"Even if core inflation does slow further in the months ahead, some FOMC policymakers are likely to have reservations about the durability of this slowdown as long as labor market conditions remain very tight."

The picture of inflation falling faster than wage growth is not quite the 1970s-style wage/price spiral often warned of in textbooks. Indeed, Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard said on Thursday she didn't see such a '70s scenario playing out.

What's more, many economists on both sides of the Atlantic have argued in recent years that only wage growth climbing above 40-year high inflation rates risked such a spiral. Anything less just embedded a recessionary real earnings shock.

Many others say the nature of the current inflation irritant is more in corporate pricing margins than labour markets.

But while energy-related and pandemic-fueled inflation can fall sharply, it might take much longer to get wage gains to fall back as fast and that changes the monetary policy calculus.

Using three-month, annualised weekly wages as his favoured measure of the return of U.S. real income growth, AXA chief economist Gilles Moec said the resilience in purchasing power may delay the slowdown in consumption needed to ensure a truly lasting disinflation.

"A price/wage race might be a better description of the issue at stake," he wrote.

"Central banks won't be able to stop before seriously impairing aggregate demand and cooling down the labour market," Moec said, pointing out studies showing there's a tipping point at which households start worrying more about keeping their jobs than the cost of living. "We are unlikely to be there by the end of Q1. This will become a much more complicated moment for them."

Graphic: Yr/Yr real wages, saving rate, revolving credit outstanding

Graphic: U.S. inflation

Graphic: U.S. unemployment

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.

(by Mike Dolan, Twitter: @reutersMikeD; Editing by Mark Potter)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.