Column-Upside Down World Of 'Reverse Currency Wars' Is Real :Mike Dolan

An upside down world of "reverse currency wars" is seeping into the real one.

Devotees of Netflix hit "Stranger Things" know well how mayhem and monsters from the show's foreboding parallel universe seep into regular daily life, with devastating effect.

Something similar appears to be happening to one of the dominant economic policy tropes of the past decade.

Financial firms, such as Goldman Sachs, have for months warned that long-fought "currency wars" - where countries struggle to prevent a weakening U.S. dollar and overvalued domestic currencies from crimping exports - could be inverted, with scary consequences.

Dubbing this twilight policy zone "Reverse Currency Wars", they reckon the re-emergence of inflation, a hawkish Fed and dollar strength would force governments and central banks to rethink exchange rate orientation and race to keep pace.

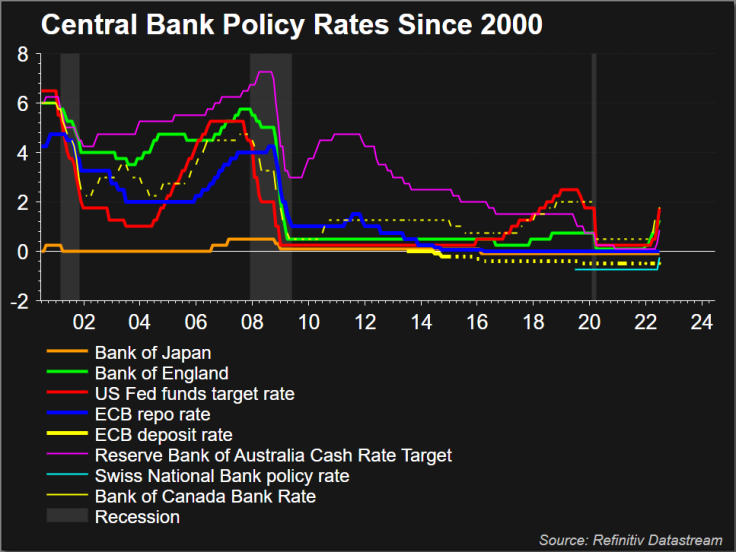

In the decade after the U.S. Federal Reserve first embarked on bond-buying quantitative easing to ward off deflation, many countries complained the resulting dollar weakness would hurt their trade in a low-growth world and force them to overheat by trying to match the Fed's easy money.

But all that changed after this year's aggressive Fed turn toward reining in 40-year high inflation with sharply higher interest rates, a halt to new asset purchases and planned rundown of its bloated balance sheet of more than $8 trillion.

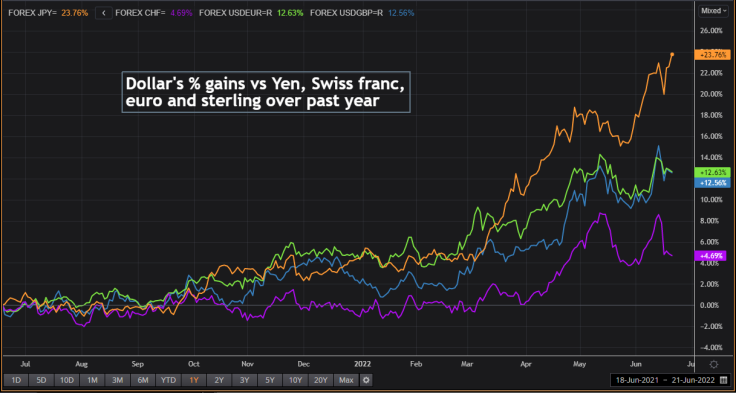

The upshot has been a rocketing dollar that's seen its index against other major currencies soar almost 20% over the past year - leaving U.S. trading partners with the opposite problem of trying to support rather than cap currencies for fear of their weakness would make dollar-priced energy and food imports even costlier, aggravating sky-high inflation everywhere.

Over the past week, 'reverse currency wars' became more of a reality.

The about-turn was clearest in the Swiss National Bank's shock interest rate rise on Thursday, a seeming shift in its overarching policy of suppressing the Swiss franc to fend off deflation toward embracing its strength as a tool to cool imported inflation. Given its standing policy led to it accumulating more than $1 trillion in foreign currency reserves in the process, the change is potentially seismic.

"The move confirms our bullish view on the franc and is the strongest evidence yet of our 'Reverse Currency Wars' thesis -- the era of targeting weaker exchange rates is over," Goldman's currency team told clients, adding that analysis showed a 1% franc rise cut 0.1/0.2 points from inflation and saying the SNB would likely seek a 5% rise in the franc's real exchange rate.

Graphic: Dollar's percentage gains over past year -

Graphic: G4 Inflation Rates Since 2000 -

'DEEPLY DISTURBING'

But it's not alone. This week Bank of England policymakers made clear they too are debating this upside-down world, nervously eying sterling's 14% drop against the dollar in just 12 months and a 5% trade-weighted pound drop this year alone.

On Monday, BoE rate-setter Catherine Mann said one of the reasons she voted for a half point interest rate rise last week rather than the quarter point delivered was to head off additional "inflation imported via a sterling depreciation."

Although her colleague and BoE chief economist Huw Pill on Tuesday downplayed explicit targeting or 'fine-tuning' of sterling - taboo in Britain since the pound was turfed out of the European exchange rate mechanism 30 years ago - the cat seems to be out of the bag. The pound is surely a major factor.

An increasingly hawkish European Central Bank is also facing record high euro zone inflation, exaggerated by blinding energy price rises and a near-15% drop in the euro against the dollar over the past year.

Only last month, Bank of France chief Francois Villeroy de Galhau warned of excessive euro weakness, saying: "A euro that is too weak would go against our price stability objective."

Japan is in a bigger pickle. It talks almost daily about excessive yen weakness - now at 24-year lows against the dollar - even as the Bank of Japan persists with a policy of capping government borrowing rates via billions of dollars of bond purchases in the face of creeping inflation and rising yields around the planet.

How long Tokyo can continue with the latter while fretting about the former is hard to tell.

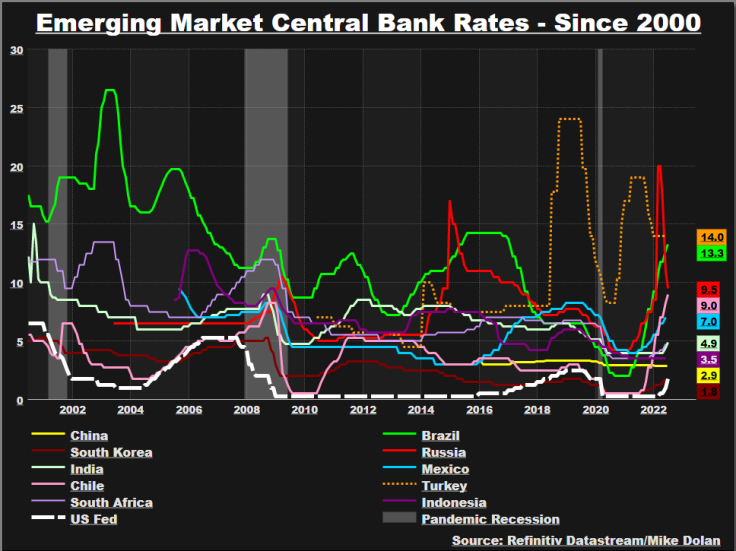

Emerging economies - many of whom face far more destabilising food and energy price inflation - have already tried to pre-empt Fed tightening over the past year. But more dollar strength could force them to turn the screw even tighter at a dangerous time.

The big risk in many people's eyes is that the Fed's pledge of an 'unconditional' war on inflation sees ever-upward pressure on the dollar in a world where dollar-priced commodity surges entrench inflation expectations everywhere and force all others to ape the U.S. central bank, for better or worse.

Citi strategist Ebrahim Rahbari reckons this all points to "overtightening" around the world - a prospect "deeply disturbing" for global markets, with lower equities, flatter bond yield curves and a severe squeeze on financial conditions.

"Reverse currency wars are strongly bearish for risk assets," he said, adding that currencies of the more dovish central banks and fragile economies are most vulnerable.

If such a crunch hastens a global downturn, there may well be great pressure on the Fed to back off. But war-driven energy problems, tight post-pandemic labour markets and political pressures ahead of U.S. mid-term congressional elections in November argue against any let up this year.

The upside down world looks here to stay.

Graphic: Major Central Bank Policy Rates Since 2000 -

Graphic: Emerging Market Central Bank Rates Since 2000 -

The author is editor-at-large for finance and markets at Reuters News. Any views expressed here are his own.

(by Mike Dolan,; Editing by Tomasz Janowski; Twitter: @reutersMikeD)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.