The Connection Between Economics and Immigration,Poor Get Poorer, More Xenophobic

Global economic crises in 2008 sparked anti-immigration sentiment in some European countries and North America and those attitudes are unwise from an economic point of view, according to an interesting research note from Swiss bank UBS AG (VTX:UBSN) on Tuesday.

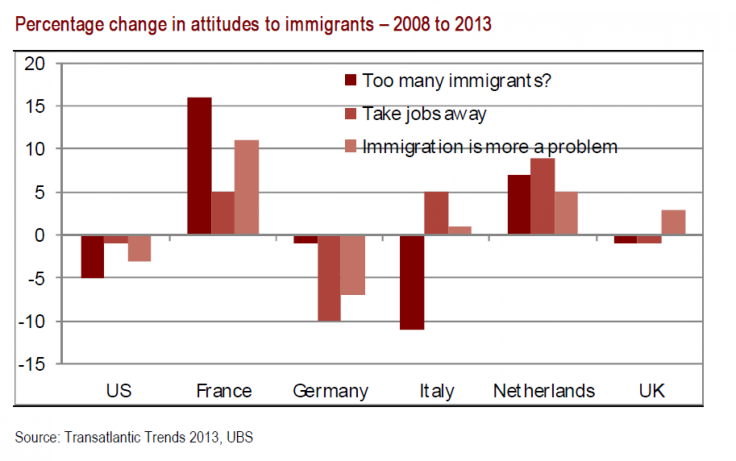

“The years of the global economic crisis have undoubtedly been accompanied by an increase in anti-immigration attitudes in some economies,” wrote UBS economist Paul Donovan. “Parties or political groups with an overtly anti-immigration attitude have experienced an increase in support – the UK Independence Party, the Tea Party faction of the Republican party, France’s Front National or the Freedom Party of the Netherlands are all examples of this,” he continued.

Later Donovan cites recent polls, showing France’s Front National at 24 percent of support among French voters, more than any other party, and the Dutch Freedom Party with a 20 percent showing.

Donovan warns that anti-immigration sentiment can have two negative impacts on the economy. First, it can harm labor markets, since immigration often grows the labor force, productivity and a diverse skillset.

“Hostility to immigration creates a less flexible labour market, and means that skilled workers may be lost to the economy,” he wrote.

But political extremism and uncertainty can also roil financial markets, who may be badly placed to judge the agendas and impacts of non-mainstream political parties. These are the parties which often voice the strongest anti-immigrant agenda.

“Markets do not tend to price political risk very well at the best of times,” wrote Donovan.

He adds that European parliamentary votes in May 2014, alongside mid-term U.S. Congressional primaries and elections in 2014, could be key for markets. “Such votes have the potential to shock investors, and may lead to a reassessment of political risks on both sides of the Atlantic.”

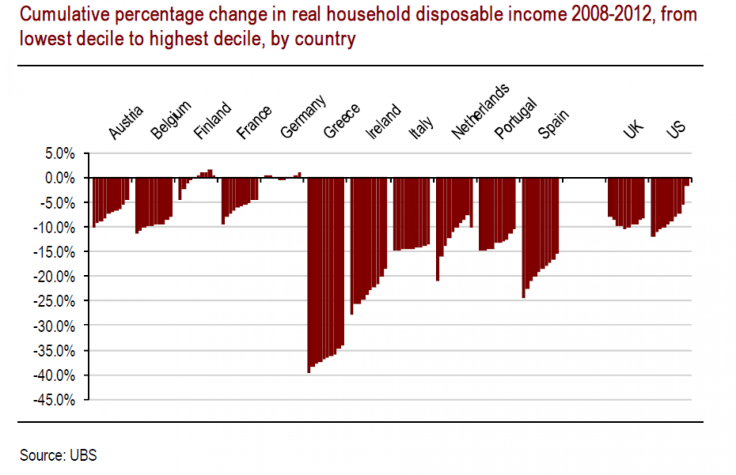

As for the underlying cause of anti-immigration sentiment, Donovan explains that the poorest people in advanced economies often lost the most disposable income in 2008 to 2012.

Growing income inequality during the crisis and restricted access to credit for poorer groups probably led to understandable frustration among poorer workers, he wrote.

“Certainly the data is suggestive of the crisis breeding increased hostility to immigration, perhaps as lower income groups (correctly) perceive both their absolute and relative income levels as falling and seek an external scapegoat to blame for their predicament,” the analyst concluded.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.