Consumer Financial Protection: Growing Watchdog Agency Faces New Tests On Anniversary Of Wall Street Reform

From a database of anonymous consumer complaints, glimpses into a person's life emerge. A Florida homeowner with a conventional, fixed-rate mortgage is dealing with Wells Fargo. The writer has lost a close loved one, and now he may lose the house.

“I have applied to Wells Fargo on XXXX [redacted] occasions for assistance with my Home Affordable Program Request. The first time when my wife passed away and now this year. This time over a years' worth of documentation. I was never served that a foreclosure process was started even by the officer on the account. I was never given an option for a deed in lieu of foreclosure, a modification denial or approval which is illegal and of course now I have placed the property on the market for sale. Please assist and protect my rights that is afforded to every consumer.”

The bank gets a chance to answer. It opts not to provide a reply that the public can view, but it responds to the consumer in Florida, and the reply is marked “Closed with explanation.”

This tale, and thousands more, reside on the website of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau for the world to see, thanks to the sweeping financial reform legislation known as Dodd-Frank, which took effect five years ago today. It’s the largest public-facing database of regular people’s complaints with the financial system. The storytelling component, added to the database last month, is but one more sign of an agency that has expanded far and fast since it opened in 2011 as part of the Dodd-Frank reform package. So far, the CFPB has collected more than 650,000 complaints about all manner of financial products, and wrangled more than $10 billion in relief for more than 17 million consumers. On Tuesday, it announced another $700 million coming to consumers, the result of an enforcement action against Citibank for deceptive marketing of credit card services.

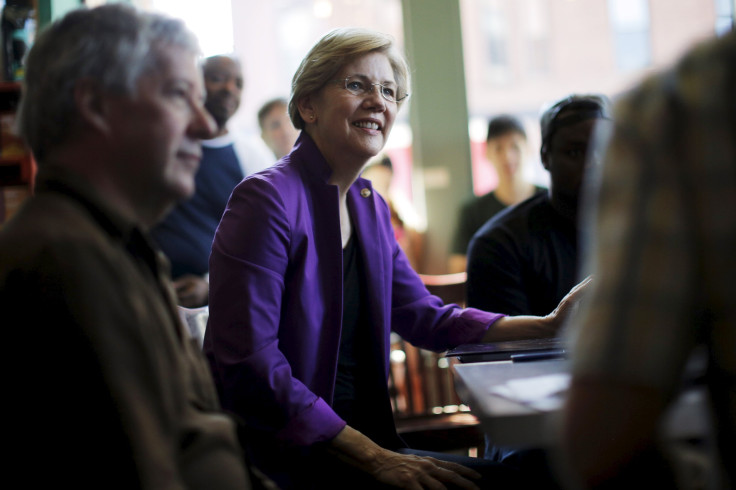

Those figures, to many consumer advocates, translate into a success story for a regulator that has continually broken ground, whether attacking hidden credit card fees, going after debt collectors, or publishing the complaint narratives, despite industry objections to naming-and-shaming. In a video released Tuesday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who first came up with the idea for the CFPB, likened the "little agency" to a David winning against a Goliath industry. “We need a world where the largest financial institutions in this country understand they can’t build their business models around cheating people," she said, "and they can’t get out there and take crazy risks and expect the American taxpayer to pick up the tab when something goes wrong."

At the same time, the CFPB’s fervor has not endeared it to the banking industry, or to congressional Republicans, for that matter. GOP lawmakers have sought ways to weaken an agency that will soon face some of its biggest tests. The CFPB is poised to curb payday lending practices, for example, and has signaled that it will take on widespread arbitration clauses, which are often buried in consumer contracts and prevent customers from suing financial services companies in court.

“The CFPB has hugely important tasks ahead of it, including a bunch of rule-makings that will make tens of billions of dollars of difference in whether consumers are treated fairly,” says Lisa Donner, executive director of Americans for Financial Reform. “And that means that the attacks both on the specific rule-makings, and the bureau’s ability to be an effective regulator, are going to be stepped up.”

From the payday lending proposal, to the supervision of major credit bureaus, to recent enforcement on auto loans, “there’s hardly an area of consumer financial services that the CFPB is not involved in in some fashion,” says Alan Kaplinsky, a partner with the law firm Ballard Spahr, which counts many financial services companies as clients.

Next month, the firm is hosting a webinar for clients on the CFPB’s long-arm reach, called “Pushing the Envelope.” The agency, Kaplinsky says, “is going to continue to expand the number of companies they are going to supervise and examine. And companies are very concerned about, What’s the limit here? Is there a limit?”

Explaining where the CFPB encounters opposition is “really kind of simple,” says Ed Mierzwinski, the consumer program director at US PIRG, and a longtime proponent of the agency. “The CFPB is making headway in all of the financial markets it’s regulating, and it’s facing resistance on Capitol Hill. The opponents of the CFPB are pretty much every financial company.”

Political spending by the financial sector reflects that, Mierzwinski says. For the 2013-2014 election cycle, the financial industry spent just over $1.4 billion on campaign contributions and lobbying, according to a report this year by Americans for Financial Reform.

That is a drop from nearly $1.6 billion of such spending in the 2012 cycle but more than the $1.2 billion that banks and financial services firms spent in the 2010 cycle, “when the industry was working to stop or weaken the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act as it made its way through Congress,” the report says.

The lobbying of members of Congress and regulators is “making a difference,” says Mierzwinski. “There’s a lot of people on Capitol Hill who think the CFPB is ‘rogue,’ to use their word, or ‘out of control,’ to use their phrase.”

GOP lawmakers have pursued two main avenues to pare back the agency: change its leadership structure, and change who controls its checkbook.

One type of legislative proposal would do away with CFPB’s one-director-in-charge model, and replace it with a bipartisan commission of appointees who have to vote on whether or not the agency can take major actions. Some would call the commission model a recipe for gridlock on big decisions.

Others, like Kaplinsky, call it a check on power. A commission, akin to how the Federal Trade Commission runs, would be “more balanced, and not be simply what one individual wants,” says Kaplinsky. “And right now, whatever [CFPB director] Richard Cordray wants, he gets.”

Another kind of proposal — such as a bill that passed recently in the House Appropriations committee — would eliminate the agency’s independent funding, and instead make the CFPB ask Congress for money under the appropriations process.

As things stand now, the CFPB is the fourth in a line of banking regulators that began receiving independent funding in 1863, when the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency was formed. (The other two are the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Federal Reserve, which provides funding to the CFPB).

If, by contrast, the CFPB had to request funds from Congress, that could mean “no money for X, or no money for Y, or starve the agency of funds,” says Lisa Donner.

President Obama would likely veto either type of attempt. Moreover, though, Donner points to evidence of bipartisan, citizen support for the CFPB.

In a survey released by Americans for Financial Reform this month of 1,000 likely voters, 85 percent of Democrats, 74 percent of Independents, and 66 percent of Republicans said they favor the CFPB's mission of rooting out deceptive, unfair, abusive practices in the market. So even though lawmakers might devote political capital to opposing the CFPB’s powers, Donner says it is not necessarily something they advertise to their constituents.

“Members who attack the bureau don’t go home and talk about it all the time,” Donner says. “It’s something that happens in Washington.”

“This is a place,” she adds, “where sunshine is our friend.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.