Could Another Superstorm Sandy Happen? Some Scientists Say No, Others Say Yes

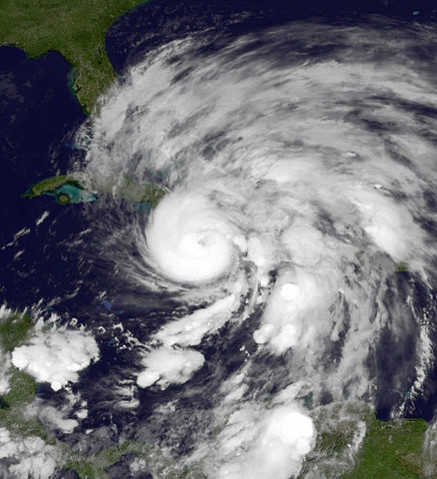

Could another maelstrom like Superstorm Sandy strike the Northeast again? Scientists are still debating whether the conditions that steered Sandy back toward the coast last year were just an atmospheric fluke, or whether they’re signs of a new normal.

Sandy was actually initially headed out further into the Atlantic Ocean after passing through the Caribbean and the Southeast, but was turned back by a high pressure system off the Canadian coast. This blocking ridge of pressure was caused by an odd bulge in the jet stream that runs from west to east high in the atmosphere.

A new study claims the conditions that steered Sandy westward aren’t likely to repeat in the next century. Colorado State University researcher Elizabeth Barnes and colleagues say in a paper published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that man-made global warming will actually decrease the likelihood that such high-pressure blobs will form. Barnes and her team examined computer models that simulate the effects of global warming in the future. The simulations predict that climate change will force the jet stream northward, decreasing the odds that a storm takes a path like Sandy’s, according to the paper.

"Sandy was an extremely unusual storm in several respects and pretty freaky. And some of those things that make it more freaky may happen less in the future," coauthor and Columbia University atmospheric scientist Adam Sobel told the Associated Press. But, he adds, "there's nothing to get complacent about coming out of this research."

But not all scientists are in agreement. Jennifer Francis, a Rutgers University researcher, has done research investigating the link between strange weather patterns and the rapid warming of the north polar region, also known as “Arctic amplification.” Francis and other researchers think that a warmer Arctic could, among other things, make the jet stream wavier, thereby actually increasing the odds that tropical storms will meet with blocking ridges that corral them away from the east.

“Large high-pressure ridges, like the one in place when Sandy came along, have been increasing in frequency, especially in the North Atlantic," Francis wrote in an email. "I am dubious that the climate models are able to realistically simulate these types of features,” she added. “The models that forecast our day-to-day weather even have a hard time predicting the formation and disintegration of so-called blocking patterns.”

Francis says one of the strongest pieces of evidence for Barnes and colleagues' conclusion is that their models predict easterly winds will decrease in a large zone north of Newfoundland. But, she says, that same model shows that the strongest decreases in wind will be just north of the area where the Sandy blocking ridge arose. This, she said says, suggests that blocking patterns like the one that turned Sandy back could become more frequent. Combine that with the fact that some researchers project an increase in late-season storms in the coming years, and storms like Sandy might not be so rare after all.

“I do hope [Barnes and her colleagues] are right, however!” Francis added.

SOURCE: Barnes et al. “Model projections of atmospheric steering of Sandy-like superstorms.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online 2 September 2013.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.