The Covid 'Longhaulers' Behind A Global Patient Movement

Snatching moments of clarity through the brain fog that was among the lingering symptoms of her coronavirus infection, Hannah Davis joined a team of similarly ill researchers and launched a study of what is now called "long Covid".

The survey was initially "for ourselves, to understand what was happening with our own bodies", Davis said. But with so little data available, it was soon informing global policymakers.

Davis is part of an international patient-led movement of people who, when they were struck down with unexplained, debilitating symptoms, developed social media networks, research and advocacy from their sick beds.

The 32-year-old likens her neurological symptoms to a "brain injury" that meant she could not drive for months and was barely able to look at a screen.

But she said the online community and her work with Patient-led Research for Covid-19 -- led by a team of five people who have never met in person -- has been "awe-inspiring".

"I really don't think that I've ever done any work that has been nearly as meaningful," said Davis, who specialises in machine learning and AI, whose group is working on a new study supported by University College London.

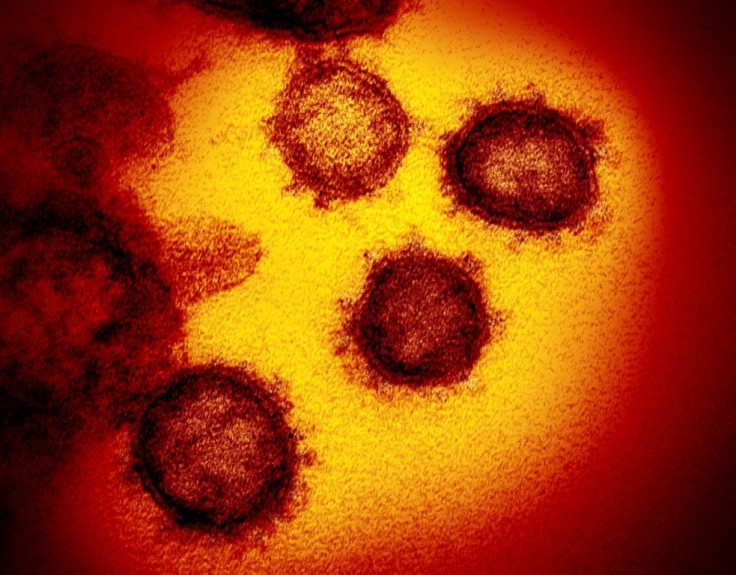

We now know that the novel coronavirus, which has killed at least 1.4 million globally, can leave even otherwise-healthy young people with lingering symptoms for weeks or months.

"To a significant number of people, this virus poses a range of serious long-term effects," World Health Organisation director general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in October.

He listed fatigue and neurological symptoms as well as inflammation and injury of major organs -- including the lungs and heart.

But in the early days of the pandemic most people believed that infection would either result in hospitalisation, or a "mild" respiratory illness that would pass in around two weeks.

Soon thousands of people were turning to social media, desperate to understand why they were not getting better.

Many share the date of their first symptoms -- Day One -- to mark the beginning of a journey with an indeterminate end.

For Davis that was March 25, when she struggled to decipher a text message from friends and later found she had a fever.

In "a hotspot within a hotspot" in Brooklyn, New York, she quickly realised it was Covid-19 and expected the illness to pass quickly.

It did not.

In April, as her neurological symptoms worsened, Davis found a Slack support group run by queer feminist wellness collective Body Politic that was attracting members from around the world.

Within days, Davis joined several other members with research backgrounds to launch a patient survey, hoping data would help sketch out a clearer picture of coronavirus recoveries.

The study involved 640 people -- mainly women in the US who most readily responded -- and was completed at lightning speed.

It flagged symptoms like fatigue and brain fog that were not yet widely recognised.

In London, Ondine Sherwood was suffering fatigue, post-exertional malaise and gastrointestinal problems when she discovered the Body Politic group and was "astonished" to see so many people with similar -- or worse -- symptoms.

She was among a group of British members who decided to form their own organisation, Long Covid SOS, to send a message to the government.

But how?

"We thought we might march on parliament, which of course would have been impossible because most of us wouldn't have had the strength or the ability to march, so we thought maybe we would go in wheelchairs, but it was lockdown," said Sherwood, a systems developer.

In the end they made a film montage of "long-hauler" stories called "Message in a Bottle" and shared it online, hoping to raise the profile of long Covid.

It worked: The film caught the eye of the WHO and the group was tasked with gathering patients for an August meeting that saw Davis present the Body Politic study and included stories of long-haul children and testimony from doctors with persistent symptoms.

The WHO has since said more research is needed into why symptoms persist and called on governments to recognise the condition.

But many patients struggle to be believed, particularly without a positive test.

Pauline Oustric represented patient groups in France, Spain, Italy and Finland at the WHO meeting, calling for recognition, research, rehabilitation and better communication.

The 27-year-old French national fell ill in March while working on her PhD at Britain's Leeds University.

She spent several months incapacitated and struggling to get help from health authorities, who told her she was not in a high risk group, before being repatriated to France in June in a wheelchair.

There she worked with other patients to set up a long Covid association, with the French hashtag apresJ20 -- after day 20.

In Italy, where long Covid is not officially recognised, 59-year-old Morena Colombi was told by her doctor she should seek psychiatric help for her ongoing symptoms.

Colombi, who has lobbied the government for recognition, set up the Facebook support group "We who have defeated Covid" that now has 10,000 members.

"I don't feel alone anymore, I don't feel crazy," she told AFP.

Juno Simorangkir, 36, created the "Covid Survivor Indonesia" group after finding support on the Body Politic network for his symptoms including heart palpitations, "extreme fatigue" and tinnitus.

Covid-19 is a "taboo", he said, and those with long-term symptoms can face disbelief from doctors, employers and even family.

A key challenge is a lack of information about the symptoms and scale of long Covid.

Research published in July by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 35 percent of symptomatic adults had not returned to normal two to three weeks after testing positive.

A study by the Desert Research Institute in Nevada, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, found that around a quarter of confirmed cases still had at least one symptom after 90 days.

Davis and her Patient-led Research colleagues have been praised as "citizen scientists" by the head of the US National Institutes of Health.

Their ongoing patient survey involves almost 5,000 participants in 72 countries.

Davis said common lingering effects include respiratory problems, memory loss, difficulty concentrating and in tasks "like being able to drive, or watch your kids, or work".

Many also suffer post-exertional malaise, drawing comparisons with myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome, although she cautions that more research is needed.

Nisreen Alwan, an Associate Professor in Public Health at Britain's University of Southampton and long-hauler, has campaigned for governments to count more than the virus death toll.

But she said defining recovery could be complicated, with some patients avoiding activities that trigger symptoms.

"You're adapting your life so that you can function," she told AFP, adding that she now limits exercise and has even changed her sitting position.

A specialist long Covid clinic in Paris diagnosed Oustric with dysautonomia -- a disorder of the autonomic nervous system.

She is back living with her parents and can only work on her thesis in 30 minute bursts.

"Research-wise it's impacted me a lot and life-wise, I can't do any physical activity, I can't lift things, I have pain every day, I'm on lots of medicines. My life is a bit of a mess," she told AFP.

"Hopefully I'll get back to my energetic self."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.