Decoding Snowball Earth, ‘A Perfect Storm’ Of Fire And Ice

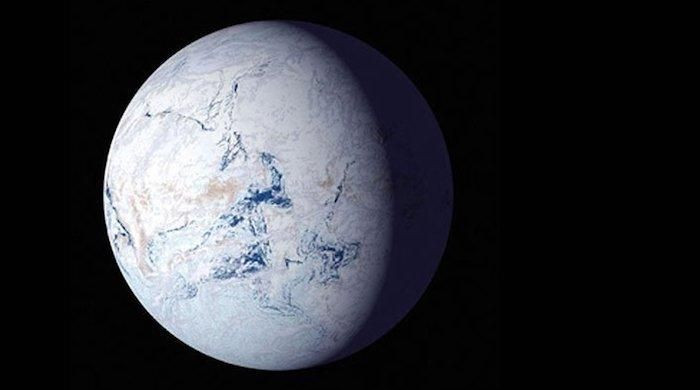

While we fret about human-induced climate change as a very real problem in the here and now, Earth has had its own natural dramatic weather cycles in the almost 4.5 billion years it has been around. One of the extreme events, which has mystified scientists for long, took place 717 million years ago and is called “snowball Earth” — the largest glaciation event in history during which the planet was covered almost entirely in ice.

A recent study, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, attempts to offer a possible answer to what caused that event. Titled “Initiation of Snowball Earth with volcanic sulfur aerosol emissions,” the study posits a hypothesis by two researchers from Harvard University’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Read: Aerosols Can Cool Earth, Fix Ozone

Around the time the event — officially called the Sturtian snowball Earth event — began, a large volcanic eruption was recorded as well, which affected a vast area, from present-day Alaska to Greenland. And according to Francis Macdonald and Robin Wordsworth of SEAS, the two phenomena were intrinsically related.

“We know that volcanic activity can have a major effect on the environment, so the big question was, how are these two events related,” Macdonald said in a statement Monday.

His team tested and rejected the idea that basaltic rocks thrown up by the volcano interacted with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to cause the cooling. That process would take millions of years and volcanic rocks in Arctic Canada coincide far more precisely with the cooling. Macdonald then asked if aerosols emitted by volcanic activity could be responsible for the rapid lowering of temperatures.

And that’s where Wordsworth, who creates climate models for non-Earth planets, came in. In principle, he said that given the right conditions, aerosols from volcanoes could have caused the “snowball Earth.”

“It is not unique to have large volcanic provinces erupting. These types of eruptions have happened over and over again throughout geological time but they’re not always associated with cooling events. So, the question is, what made this event different?” he said in the statement.

Geological and chemical analysis of the region, known as the Franklin large igneous province, showed a sulfur-rich sediment through which the volcanic rocks erupted. The sulfur would have mixed with the atmosphere during the eruptions, forming sulfur dioxide, which was very effective at blocking solar radiation when it reached the upper layers of the atmosphere.

Read: Great Barrier Reef Almost Drowned 125,000 Years Ago

At the time when these eruptions took place, 717 million years ago, the Franklin large igneous province was near the equator, making it easier for the sulfur dioxide plumes to reach, and cross, the stratosphere and the troposphere. Beyond the troposphere is where sulfur dioxide is most effective at reflecting solar radiation.

But the situation was brought to a critical point by the extent of volcanic activity at the time, which spanned about 2,000 miles over Canada and Greenland. The volcanoes were almost continuously erupting, and about a decade of that would put enough aerosols in the environment to thoroughly destabilize the planet’s climate.

As the planet cooled, ice started to form, and once it crossed a critical latitude, around present-day California, it took over and did the rest. More ice meant more reflection of sunlight back to outer space, which led to further cooling, which led to more ice, and so on, creating the “snowball Earth.”

“This research shows that we need to get away from a simple paradigm of exoplanets, just thinking about stable equilibrium conditions and habitable zones. We know that Earth is a dynamic and active place that has had sharp transitions. There is every reason to believe that rapid climate transitions of this type are the norm on planets, rather than the exception,” Wordsworth said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.