Dinosaur Feather And Blood Discovered In Amber Fossils Show Parasites Feeding

Scientists might have found an extinct tick with a belly full of dinosaur blood, one fossil in a group that suggests these parasites were sucking on dinosaurs long before they fed on humans.

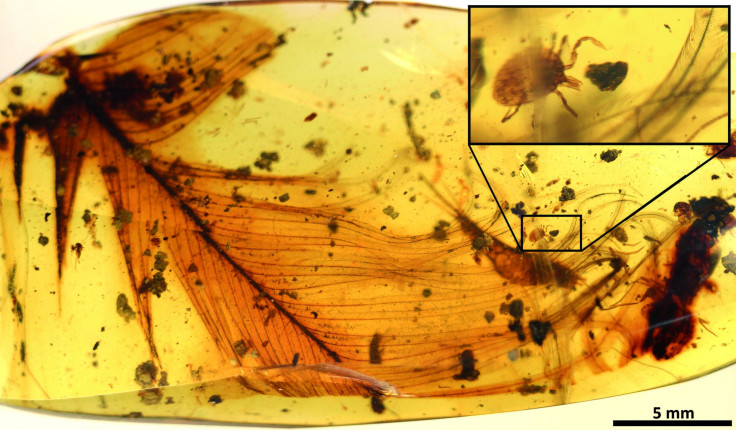

Their discoveries also include a tick that was preserved in amber while grasping a dinosaur feather. That fossil dates to 99 million years ago, putting it in the middle of the Cretaceous period, according to a study in the journal Nature Communications.

The scientists described the feather as “pennaceous,” meaning it was the kind of feather you might imagine when picturing a quill, with a hollow base stuck in the skin. Although similar to the kinds of feathers birds have today, it came from a feathered dinosaur, according to the study.

Together, the findings offer evidence of dinosaur blood-sucking tick behavior.

“The discovery is remarkable because fossils of parasitic, blood-feeding creatures directly associated with remains of their host are exceedingly scarce, and the new specimen is the oldest known to date,” the University of Oxford explained in a statement, referring to the feather-clutching tick. “The scenario may echo the famous mosquito-in-amber premise of Jurassic Park, although the newly-discovered tick dates from the Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago) and will not be yielding any dinosaur-building DNA: All attempts to extract DNA from amber specimens have proven unsuccessful due to the short life of this complex molecule.”

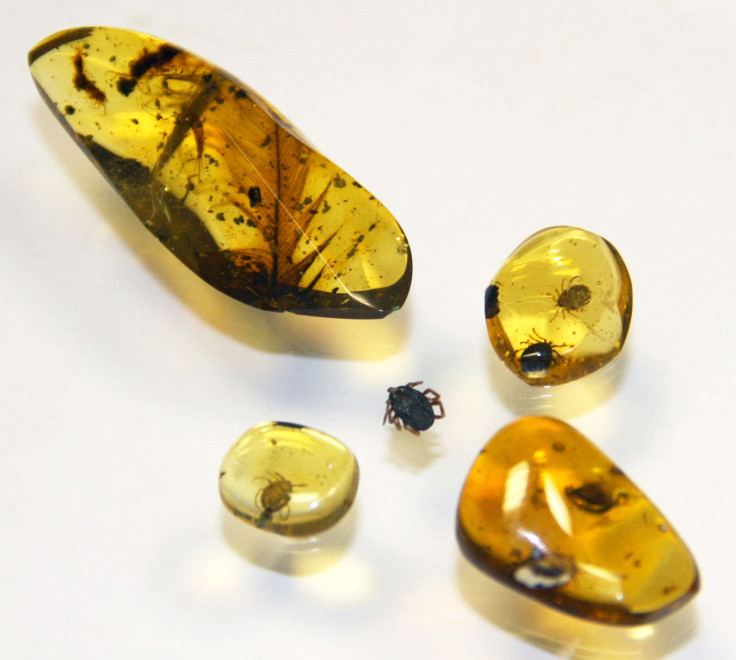

While the tick holding onto the feather is direct evidence that these parasites were feeding on dinosaurs, the other specimens offer indirect evidence. A new species of extinct tick known as Deinocroton draculi, which translates to “Dracula’s terrible tick,” was found sealed up in amber — one of them becoming trapped in the amber “soon after it dropped from its host, once it had completed its blood meal.”

The blood was not preserved cleanly enough for the team to determine which animal it came from.

“Assessing the composition of the blood meal inside the bloated tick is not feasible because, unfortunately, the tick did not become fully immersed in resin and so its contents were altered by mineral deposition,” researcher Xavier Delclòs said in the Oxford statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.