Divining Intervention: Drought-hit Californians Enlist 'Water Witch'

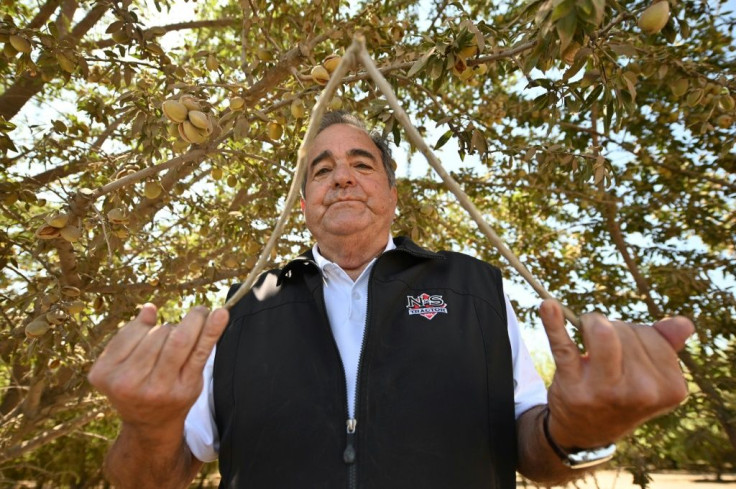

Holding a V-shaped branch point down, David Sagouspe examines the cracked soil of a California farm. Under the blazing sun, he takes a breath and sets off, mechanically turning the branch five times towards the sky and five times towards the ground.

He stops, marks the spot with a pink flag and nods. "People would pay a lot of money for that strata right there," he says, referring to underground water.

For more than 40 years, Sagouspe has worked as a dowser, also known as a "water witch," offering to help the largest farmers in central California find groundwater.

Proudly claiming to live in "America's orchard" but desperate in the face of increasingly extreme droughts, farmers are turning to him more and more.

In order to find water in a region that severely lacks it, Sagouspe can't use just any piece of wood. "Some people use willow, but it is too fast-reacting for me," he says, as if it were obvious.

His tool of choice is a piece of olive wood, wrapped with black tape around the bottom, that he keeps on the dashboard of his white pickup truck.

"The stick, it becomes almost bonded to me," he says. "When I witch from my truck, it starts tingling in my hands when i know there's going to be water."

Sagouspe swears he doesn't use any tools, maps or geological surveys in his work. "I'm a renegade," the 70-year-old says mischievously.

Instead, he bases his work on very precise knowledge of the region and the neighboring mountain range that irrigates the valley with water -- when there is any. His father, who transferred this "energy" to him, also worked as a dowser in the area.

Sagouspe offers to "pass that energy down" to AFP, but without much success.

For each supposed water source that he marks with his little pink flags, Sagouspe makes $1,000.

During the severe drought in 2014, "I paid for my daughter's wedding, I had so many people calling me," he says. In 2021, with orchards parched, animals dehydrated and farmers panicked, he also stands to make record revenues.

Farmers who hire the dowser have no guarantee of actually finding water at the spots he marks. They then have to pay tens, even hundreds of thousands of dollars to build wells and extract water -- or come home empty-handed.

But they take that risk because specialized companies cost more, without necessarily being more precise, says Bikram Hundal, a farmer who in the past dug an expensive well nearly 900 feet (300 meters) deep without finding even a drop of water.

During his first meeting with the dowser, Hundal -- whose company packages 20 million pounds (nine million kilograms) of almonds per year -- said he didn't take Sagouspe seriously.

"Are we doing a probe, are we using a satellite?" Hundal, standing in the middle of his almond field, recalls asking. "He said, 'No, I can feel the electromagnetic currents of the water.'"

"I was like, 'This is BS,'" says Hundal, who has an engineering background.

But then...

"I've used him five times, and he's been successful five times," says Hundal.

Experts bristle at such examples, arguing that if you dig deep enough, you can find a certain amount of water almost anywhere.

But it won't necessarily be of high quality, and digging it up can endanger already fragile water tables.

"The dowser commonly implies that the spot indicated by the rod is the only one where water could be found, but this is not necessarily true," warns the United States Geological Survey.

Sagouspe insists that the wand doesn't lie. "Sure, you're going to have your skeptics," he says, shrugging.

"Until you have a ranch that is completely dry," he adds, smiling. "Then, call me."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.