Do Wellness Programs Work? As Companies Buy In, Return On Investment Is Coming Under Scrutiny

For Lisa Li Moye, the reward for 70,000 steps taken over three months came in the form of a $70 gift card from her health insurance company. She spent the money on an organizer for her husband.

“His stuff was everywhere,” Moye, a 28-year-old resident of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, said — his hats, keys, wallet. “It drove me crazy.”

In the current health conscious, data-driven age, reasons for hitting the gym are no longer limited to the standard promises of feeling and looking better. Now, people increasingly have the option of racking up financial rewards and other perks through wellness programs offered by numerous insurers and employers. As these initiatives blossom from a fringe idea to a standard corporate benefit, however, they are also coming under closer scrutiny, and it turns out that their actual impact varies considerably. In some cases, they don’t appear to help employees become healthier or happier at all.

“It really is a completely new world in terms of employer wellness programs,” said Ben Isgur, the director of PwC’s Health Research Institute, which does research and analysis on issues related to health and business. As for the effectiveness of these programs, Isgur said, “It truly is all over the map.”

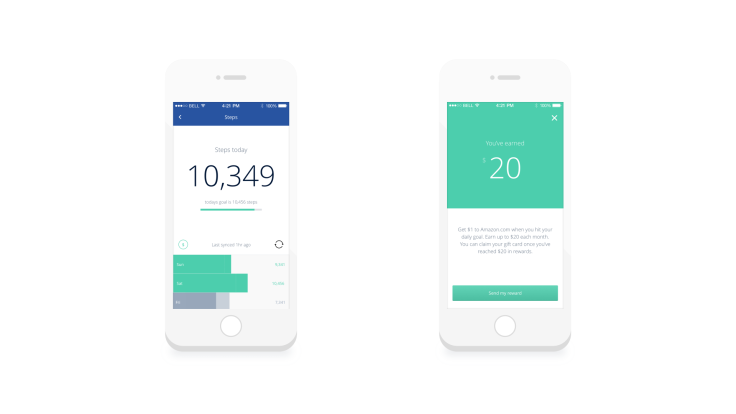

Wellness programs come in all shapes and sizes. They can be run by a company itself, an insurer or a third party. They might come in the form of Amazon gift cards whose amount is tied to the number of steps taken each day, as Moye’s insurer, New York-based startup Oscar, offers. They might also be in the form of cooking classes or other training for employees enrolled in programs to lose weight. On Tuesday, health insurer Aetna announced that it would pay its employees up to $500 a year to get seven straight hours of sleep in a night.

“Wellness programs are getting much more sophisticated,” Isgur said. “There’s a lot more technology to help deliver and monitor those programs.”

Most employers prefer the carrot to the stick, but they are also legally allowed to penalize employees financially. The 2010 Affordable Care Act allows employers to offer incentives of up to 30 percent of an employee’s monthly insurance premium to encourage them to join wellness programs. In some cases, those who don’t join or who fail to meet certain goals must pay more. Experts fear this provision might effectively allow employers to legally charge sicker employees higher premiums, even though the Affordable Care Act barred insurers from doing just that.

The overarching principle behind all of these programs is that they give people incentives to lead healthier lives, in the long run reducing medical expenses for employers and employees alike. Some programs are also aimed at making employees happier, more productive and more loyal to their companies. Fueling this interest are several factors, chief among them rising healthcare costs and a broader cultural shift toward being more health conscious.

Employers “are looking for ways to cut costs,” Isgur pointed out. “One of the ways you can reduce your costs is to have healthier employees.”

By one estimate, 79 percent of employers in the U.S. currently offer employees some sort of wellness program. The Corporate Health and Wellness Association, a nonprofit trade group, suggests the proportion is even higher, at 90 percent in 2013, up from 57 percent in 2009. Overall, corporate wellness is an $8 billion industry, and IBISWorld projects it will grow 8.4 percent annually, to rake in revenues exceeding $12 billion by 2020.

Employers are also investing more heavily in these programs. In 2015, they put into wellness programs an average of $693 per employee, up from $430 in 2010, the National Business Group on Health has found.

Now, the looming question is: Are wellness programs worthwhile? The answer to that question varies as widely as the programs themselves, studies suggest.

If companies try to calculate, dollar for dollar, whether savings generated by these programs outweigh the costs, then “what our data suggest is clearly no,” said Soeren Mattke, a senior scientist at the nonprofit RAND Corp. who worked on a report sponsored by the Departments of Labor and Health & Human Services on workplace wellness programs.

And when employers try to use other metrics — workplace productivity, for instance, or employee retention — those end up being notoriously difficult to measure.

“It’s hard research,” Mattke said. “You’re not running a clinical trial where you can randomize people.”

Some insurers maintain that wellness programs offer a big bang for their buck.

Humana says that its Vitality program saves companies an average of $5.81 for every dollar spent on wellness programs. Employees engaged in the program visited emergency rooms and hospitals fewer times, and they missed less work than those who weren’t active in the program. But the study excluded high-cost individuals with more than $100,000 in medical claims each year.

In an email to International Business Times explaining the exclusion, Humana spokesperson Marina Renneke wrote, “The nature of health claims costs means that there can be a handful of very high claimants that skew the results for the entire population.” Removing the high claimants was done “to accurately reflect the difference between engaged and unengaged members” in the Vitality program, she said.

Oscar, the New York-based insurer, has said it is too soon to tell what kinds of savings, if any, are generated by the rewards it offers members like Moye. Other studies have called into question the effectiveness of wellness plans for employees trying to lose weight.

And for the people actually enrolled in wellness programs, success can mean something else entirely.

The first year after she joined Humana Vitality in February 2012, Sarah Eggers was thrilled. As part of the benefits at the small company where she works in a suburb of Kansas City, the program allowed her to rack up points she could put toward one of her — and her husband’s — favorite pastimes: going to the movies. In 2013, the couple saw “The Hunger Games,” “Man of Steel,” “Thor,” “Star Trek” and the “Great Gatsby” together — without paying out of pocket for a single ticket.

“I was just saving up so many points,” Eggers, a 29-year-old self-described elliptical lover, said. “I had the added incentive that we could be saving $12 a pop on movie tickets if I worked out regularly.” She could also accumulate points if she met a daily goal of steps taken, tracked by the FitBit pedometer she wore on her wrist.

But gradually, the novelty wore off. “After a while, you kind of forget about it,” she said. Her FitBit broke in 2014, and she has yet to buy another, although she said she was considering doing so soon.

Moye, the Brooklyn real estate broker, experienced a similarly diminished enthusiasm for Oscar's program.

“In the beginning I was really excited. I was like, ‘We’re going to make money every day,’” she recalled. She would urge her husband, who also has insurance from Oscar, “Walk some more.”

But the rewards program, which included Oscar's defraying the cost of a gym membership, wasn’t dramatically changing her way of life, Moye said.

“I’m going to the gym anyway,” she said. “I’m naturally active. It’s not like it’s anything extra for me.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.