Donald Trump Qualifications For Office: He Is A Business, Man, But Is That Good For The Country?

With the presidential election days away, Americans are choosing between a woman who has spent decades in the public sector and a man who has spent decades in business.

Donald Trump’s business acumen, or lack thereof, aside, many have argued over the merit of the idea that a country can be managed like a company—and, by extension, whether someone like Carly Fiorina or Herman Cain or the current Republican nominee could make a good commander-in-chief. Prior to Trump, the most recent businessman to make a strong run at the White House was Texas billionaire Ross Perot in 1992.

Real-life examples tell us that former executives may have an advantage over career politicians when it comes to putting talented people in the right positions and leading with efficiency. But in other areas where they're commonly thought to have an edge on those who've spent their lives in the public sector, such as trade and budget management, the benefits of corporate experience aren't so clear.

In the first presidential debate on Sept. 27, Trump touted his business background as evidence that he would improve the United States’ trade balance.

“When we have a country that’s doing so badly, that’s being ripped off by every single country in the world, it’s the kind of thinking that our country needs, because… we have a trade deficit with all of the countries that we do business with, of almost $800 billion a year,” he told Lester Holt. “You know what that is? That means, who’s negotiating these trade deals?”

However inaccurate the statement, Trump hinted at what some more successful corporate moguls consider a valid argument. In a 2013 interview with Politico, philanthropist and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates criticized government deadlock by comparing it to poor corporate management.

“You don’t run a business like this,” he said, adding that he wished the president had more decision-making power over the legislative branch. “A business that is maximizing its output would proceed along a different path.”

More recently, billionaire investor and Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban told "Late Late Show" host James Corden on March 11 that, while he thinks Trump has “gone crazy,” he still thinks a corporate executive is fit to be president.

“As a business person, you have to get things done,” he said. “Politicians are hated because nothing happens. Running a company, you either get it done or you disappear.”

But while some presidential candidates—such as former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, who painted himself as a “CEO governor”—hold the belief that private-sector leaders own exceptional budgetary talents, the reality is less certain. Balancing state budgets is a requirement for every state with the exception of Vermont, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, but some leaders manage to maintain state budget surpluses.

Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, for example, studied finance at Arizona State University before founding Cold Stone Creamery, which he transformed from a local shop to a franchise with 1,400 locations in 50 states and 10 countries before selling it in 2007. While his business resume isn’t spotless—Cold Stone’s profits fell 89 percent while the number of franchises tripled between 2003 and 2006, the Arizona Republic reported—he has trimmed Arizona’s budget.

After implementing a hiring freeze for state employees, he signed a budget in May that Arizona’s Joint Legislative Budget Committee estimated would leave the state with a surplus of $66 million by the end of the next fiscal year.

Arizona Republic columnist Robert Robb, a self-described conservative with libertarian leanings, said thanks to the state employee hiring freeze, Ducey was able to avoid a potentially unpopular tax increase.

“At the time he became governor, given the deficit he faced, it was an appropriate decision to make, a necessary decision to make,” Robb said in a phone interview with International Business Times, adding that K to 12 education programs could have used some more state funding. “What he did was refinance state programs… it’s at a level of government services that is substantially below the former level.”

Of the six states categorized by the Pew Charitable Trusts as the most fiscally healthy, just one has a governor who came straight from a business background. Of the six deemed by Pew as least healthy, one came straight from the private sector. Three governors in both categories had significant corporate experience but had roles in the public sector before serving as chief executives in their states.

In the George Mason University Mercatus Center Center’s 2016 ranking of the 50 states by fiscal condition, two governors of the 11 states with above-average fiscal health came straight from the private sector, but the same could be said for the 10 states that exhibited below-average fiscal health. Nine of the 11 states with relatively sound budgets had governors with significant business backgrounds, while five of the 10 with worse-than-average budget issues were led by governors with significant business backgrounds.

And there are, of course, major examples where private-turned-public sector leaders have presided over ballooning deficits.

George W. Bush, whose post-Harvard Business School oil ventures weren’t exactly successful, made millions when he bought the Texas Rangers baseball team in 1989 for $600,000 and later sold it for $14.9 million.

But as president, Bush took the $236.9 billion budget surplus Bill Clinton handed off to him and turned it into a $1.4 trillion deficit by 2009.

“Bush’s financial dealings were much more successful than his presidency in many respects,” Jean Edward Smith, the author of the 2016 biography “Bush,” told IB Times.

Outside of his 2001 Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act—commonly referred to as the Bush tax cuts, as it created a new lower income tax bracket and reduced rates across the board, helping to unbalance the budget—Bush didn’t really use his private sector experience, according to Smith. And when serving as chief executive of the Lone Star state, Bush was “more like a cheerleader of Texas” than a governor, the biographer added, as the state’s lieutenant governor is commonly considered to have more power than Texas' formal top leader.

But others noted that the so-called “fiscal responsibility”—the ability to keep budget figures positive, often associated with business leaders-turned-politicians—may not be the most responsible option in government when needs include educating students and helping low-income people.

Florida Gov. Rick Scott, who left his position as Hospital Corporation of America Chief Executive Officer in 1997 amid a fraud investigation, signed a budget in June that is expected to give his state a $1.4 billion surplus for the year. On the Mercatus rankings of states by fiscal health, Florida was sixth.

But the exiting Florida House minority leader didn’t see this as any sort of accounting achievement.

“That’s all bulls---. Balancing the budget is a constant requirement,” Democratic State Rep. Mark Pafford of West Palm Beach told IB Times. “It takes courage to do something different.”

Pafford pointed to public health care cuts as examples of where extra money could have been spent productively. While a company is obligated to score profits so that it can pay off shareholders, a government manages taxpayers’ money and is obligated to do so responsibly, he added.

“The government is not a corporation. The government is a representative body of the people,” Pafford said. “It is given the people’s money and it is responsible for taking care of the people.”

In terms of competing interests and varying demographics, Pafford is right: a government is not, by any means, a business. Companies like McDonald’s, IBM and Volkswagen may boast employee numbers in the hundreds of thousands—or, in the case of Walmart, millions—but they’re dwarfed by states and large cities in terms of size and diversity, and, many argue, cannot be run by a unilateral authority.

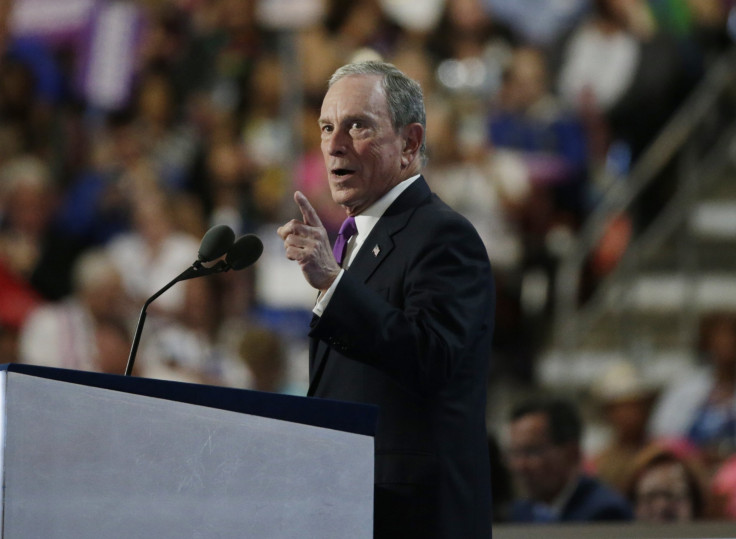

One leader who recognized this was former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. After investment bank Salomon Brothers laid him off with a $10 million severance package in 1973, Bloomberg created what is now Bloomberg L.P. , a provider of business information and data with 325,000 subscribers worldwide, as well as flagship TV, digital and radio news. The billionaire philanthropist, who lambasted Trump in a speech at the Democratic National Convention over the summer, left his CEO position when elected mayor of New York City in 2001. He was re-elected in 2005, and again in 2009.

“New York [City] is very large—it’s a very large government—and you can’t run every department,” Joyce Purnick, a New York Times columnist and author of "Mike Bloomberg: Money, Power, Politics," told IB Times. The very managerial Bloomberg “wanted to control everything,” but such control was impossible at the mayoral level, let alone for a state, she added. His answer to this problem was a corporate one: hire talented people.

“He didn’t do it unilaterally. He knew they knew what they were doing,” Purnick said in reference to his government employees, “And he let them do what they were doing.”

Not all of his hiring decisions were successful ones, Purnick noted, pointing to Public Schools Chancellor Cathie Black, the former chairwoman of Hearst Magazines, as a failed appointment due to her inexperience and unpopularity. (Bloomberg himself, usually a stubborn defender of his own appointees, removed her from office just three months after she started.) But his penchant for risk-taking set him apart from other public-sector leaders, which also worked to his benefit, Purnick said.

Of course, a business background doesn’t always translate to the best personnel decisions.

Among a laundry list of criticisms directed at Scott, Pafford noted the Florida chief executive’s firing of the state’s top law enforcement officer Gerald Bailey, who had been at the Florida Department of Law Enforcement for two decades and spent eight years as its commissioner, for what turned out to be purely political reasons.

“Like in business, Gov. Scott thinks it’s good to frequently get new people into government,” Scott’s office said in a statement, according to local papers. He later apologized for the unpopular dismissal.

Bloomberg, according to Purnick, more or less confirmed Gates’ belief that private sector leaders can get things done in the face of bureaucratic gridlock.

“He initiated all of the bike lanes, he initiated the idea that Times Square become a pedestrian area and a mall,” Purnick said. “His attitude in business was just as his attitude in governing was: you can’t be hurt by trying.”

Bloomberg, who Purnick described as “very willful, and determined, and bossy,” successfully took over the city’s stalled Sept. 11 memorial project in 2006—an initiative his biographer said was certainly aided by his business acumen. In 2006, nearly two years after its Board of Directors met, Bloomberg appointed himself board chairman of the project, persuaded conservative billionaire David Koch and liberal satirist Jon Stewart to join him, won $10 million in funding from American Express and injected $15 million of his own money into the memorial.

Fostering trade relations, however, can be tough for a business leader, or anyone really, with little foreign experience.

While Ducey has touted his ability to negotiate new trade deals with neighboring Mexico, the year-over-year growth rate of imports to Arizona from Mexico has remained flat, and year-over-year export growth from the state to Mexico has fallen over 2015, Ducey’s first year of office, according to data from Arizona-Mexico Economic Indicators.

Scott, who favors free trade and also supports Trump, who is against trade openness, has used his position to try and open Florida to more global commerce. But while Scott has made trips to Chile in an effort to bolster trade relationships between Floridian and Chilean companies, Florida’s exports have actually declined during his tenure.

For political rookies, understanding global affairs may pose another problem.

While not representative of all businesspeople, Herman Cain, former CEO of Godfather’s Pizza, encapsulated this issue for an exec-turned-commander-in-chief in an October 2011 interview with CBN News’ David Brody: “And when they ask me who is the president of Ubeki-beki-beki-stan-stan, I’m going to say, you know, I don’t know.” Libertarian presidential candidate Gary Johnson, who founded a large construction company before becoming governor of New Mexico, did the same this year when he asked, “What is Aleppo?” in an interview on MSNBC.

.@mikebarnicle: What would you do, if you were elected, about Aleppo? @GovGaryJohnson: And what is Aleppo? https://t.co/ZbqO5RAEsk

As for Bush, who had many more opportunities than any governor or mayor to engage in diplomacy, Smith said he doesn’t think the 43rd president’s experience in the oil industry or presiding over the Texas Rangers was much help.

“I think that Bush believed Saddam Hussein was evil,” Smith told IB Times, dismissing the possibility that Bush’s oil business work served as any sort of motivation to invade Iraq. Smith’s biography of the former president is a bit more to the point, predicting that the invasion of Iraq would “likely go down in history as the worst foreign policy decision ever made by an American president.”

For his part, Trump, in his attempt to lead the U.S. on the global stage, has called Mexican immigrants rapists, encouraged Russia to hack his opponent and declared that he would not defend eastern European allies from Russian threats, among other remarks.

So what makes some corporate leaders more successful than others in moving from business to the public sector? It might be their willingness to learn the difference between the two.

Scott, according to Pafford, treated the government as a business without adjusting to his new public-sector role.

“He turned his back on how it’s been done,” Pafford said. “He never took time to invest in how government operates.”

Bloomberg, Purnick told IB Times, “studied the city and city government before he became mayor.” She added that for the two years he spent considering running for office, Bloomberg questioned incumbents about how they did their jobs.

“He asked them what it was like," Purnick said. "He really studied them, and he did a pretty good job."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.