Ebola Quarantines In The US: Holding Travelers Against Their Will Is Complicated

Imagine being isolated for three weeks in a government facility because of a wrong answer on a federal form. That's the potential nightmare that could await travelers coming from West Africa to the U.S. under new airport screening policies slated to take effect Saturday.

The new travel measures aimed at keeping Ebola out of the country will require passengers from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone to answer a series of health-related questions, including whether they have been in contact with an Ebola patient. They will also have their temperatures taken by health agents. Possible or suspected Ebola carriers would be pulled aside for further questioning and, if deemed a risk, transferred to a quarantine station at the airport. The screenings will take place at five of the busiest international airports in the country.

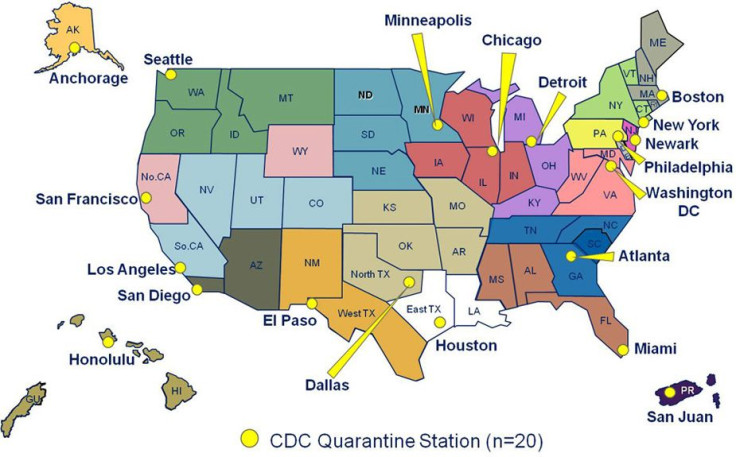

Federal law allows the U.S. government to sequester people who may pose a risk of spreading infectious diseases, a measure that could lead to some airline passengers being quarantined at one of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 20 holding stations across the country. Quarantining people on an ad hoc basis, however, has its challenges. Health officials will have to balance a traveler's right to not be quarantined against his or her will with greater public health concerns. The airport screenings raise the possibility of the government holding someone for up to three weeks, the longest the virus is known to incubate before symptoms occur, who may not have Ebola in the first place.

Antibodies of the virus that indicate an infection only show up in tests once someone has symptoms. A person in the early stages of the illness would likely test negative, experts have said. But what if the person never had the virus in the first place? “The symptoms [of Ebola] can mimic many other symptoms and in fact mimic what might more likely be other infectious diseases ... from that region, including Malaria,” Michael Misialek, associate chair of pathology at Newton-Wellesley Hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, told International Business Times.

Malaria is not one of the diseases included on the CDC’s list of illnesses allowed for quarantine. The list includes cholera, diphtheria, infectious tuberculosis, plague, smallpox, yellow fever, viral hemorrhagic fevers (including Ebola) and severe acute respiratory syndromes. Unfortunately, there is no quick way to test for Ebola. Tests are typically sent to state labs, Misialek said, and can take a while to process.

Then there’s the added complication of whether a quarantined person's job is secure or if they will be compensated for his or her days in isolation. "They're symptom free, and they’re well, and they don’t feel like spending three weeks … out of commission," Mark Rothstein, a law professor at the University of Louisville, told the Washington Post. Only 10 states have laws protecting employees who have been quarantined from being fired, the Post noted.

The government’s power to quarantine in the name of public safety has a long history in the U.S. and has proved effective at preventing some deadly diseases from ballooning out of control -- for instance, quarantines spared Philadelphia from a widespread yellow fever outbreak in the late 18th century. The CDC has not quarantined someone since 2007, when a man with a dangerous form of tuberculosis was involuntarily isolated in Atlanta. Quarantined individuals receive shelter, food and care, including the latest medical interventions such as vaccines or antibiotics, at a designated emergency facility or hospital, according to the CDC.

A quarantined individual can challenge his or her detainment by petitioning for a writ of habeas corpus, however courts generally uphold detentions “as valid exercises of a state’s duty to preserve the public health,” the Congressional Research Center noted.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.