Ebola In The US: Front Line Health Training Trickles Down To First-Year Med Students

When 26-year-old Hunter Smith, a first-year medical student at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington, Connecticut, received an email Thursday informing him of mandatory Ebola training during the weekend, he was surprised. Required weekend trainings for students were extremely rare, Smith said, and typically happened after things like widespread blackouts or the 9/11 terrorist attacks. As someone with only a few months of medical school under his belt, Smith would be coached in how to deal with an Ebola patient, the same kind of training currently being given to veteran health workers across the U.S.

Nurses, medical clinicians, students and even airport workers represent the first line of defense against an Ebola outbreak. These people will likely be the first to come into contact with a patient at an urgent care facility or a primary care office, or as the person steps off a plane from West Africa. Amid fears of Ebola spreading in the U.S. following a deadly case in Texas and the subsequent infection of two nurses there, the people at the bottom rungs of the health care system hierarchy are being taught what to ask patients and how to get in and out of personal protective equipment. “Every single ‘t’ has been crossed and every ‘i’ has been dotted,” Smith told International Business Times. “I have Ebola training as a first-year medical student. They’re getting everybody.”

Medical students have very little clinical contact with patients, but they often work part time at primary care offices taking medical history. It's possible but rare for a medical student to be the first person a visiting patient speaks to at the office. Smith said the mandatory training, led by the center’s “head honcho,” the chief of medicine, emphasized getting patients’ travel histories, including whether they had been to Guinea, Liberia or Sierra Leone, where the Ebola death toll is upward of 4,500 people and growing.

“We’re assuming nothing now,” Smith said. “Before this crisis, those kinds of questions weren’t asked as often.” Now, he said, everyone is told to proceed as if they are the first people asking. “They mentioned several times that they’re trying to avoid what happened in Texas,” Smith said. Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy declared a preemptive public health emergency for the state Oct. 7, which authorized the state Department of Health to quarantine and isolate people suspected of having Ebola.

In Dallas, where Thomas Duncan, a Liberian visiting the U.S., was diagnosed with the virus and died, hospital staff initially failed to identify Duncan as an Ebola patient even though he informed them he'd recently arrived from West Africa. It was a mistake that some have criticized as having led to Duncan’s death. Dozens of people were exposed to Duncan during the time he was symptomatic, something that could have been avoided had the hospital not sent Duncan away on his first visit. Roughly 120 people who were around Duncan are still being monitored for possible infection, Texas health officials said Monday, the Associated Press reported.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Monday it was changing its guidelines to require nurses treating patients affected or possibly affected by Ebola to fully cover their bodies with protective gear. The move follows criticism that health workers at Dallas hospital did not take adequate steps to keep themselves from getting sick after two nurses who treated Duncan tested positive for the virus.

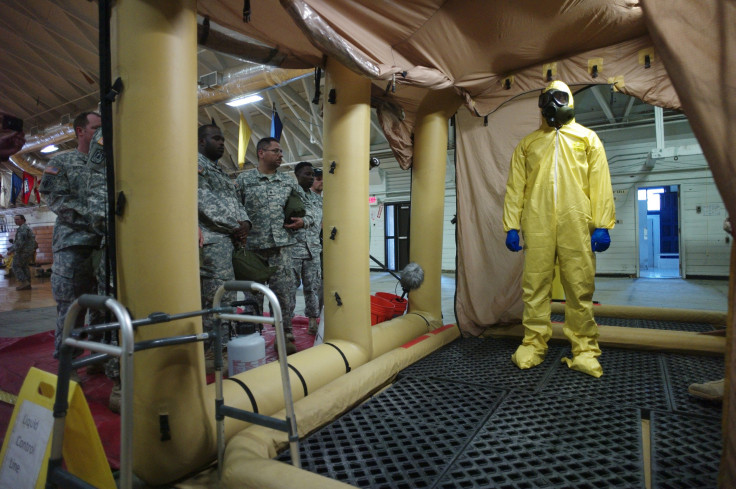

The CDC has a mock Ebola ward in Anniston, Alabama, where health officials showed medical clinicians how to properly put on safety suits, CBS News reported. Smith said he and other first-year med students at UConn were also shown how to put on and take off protective gear. Officials emphasized the “buddy system,” Smith said.

“Whenever you’re with an Ebola patient, you need someone there watching you to make sure there’s no contact between the suit and the skin or anything,” he said. One of the things students were taught to do was to apply antiviral liquid to their protective gloves before they remove them. Hands have to be sterilized with antiviral liquid, too, before the face mask can be taken off.

Smith spent two years in Cameroon with the Peace Corps after completing his undergraduate education at the University of California, Los Angeles. He drew parallels between the misinformation about disease he witnessed in Cameroon with the mistrust and hysteria in West Africa surrounding Ebola. “In my village, there was a rumor going around that if you went to the hospital in the area with malaria, they would kill you,” he said.

In the U.S., however, people are generally aware that Ebola is a virus that can be treated. “The public believes in science,” Smith said. “We take measures that people in West Africa are not able to take.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.