Ecuador Banned Amazon Oil. Brazil's Lula Wants To Drill

The timing spoke volumes: just as Ecuador announced its historic decision to halt oil drilling in a sensitive Amazon rainforest reserve, Brazil trumpeted its massive fossil-fuel investment plans -- which include oil exploration near the mouth of the Amazon river.

Oil is an increasingly uncomfortable subject for Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who casts himself as a climate crusader, but also faces criticism for his plans to grow Latin America's biggest economy with fossil fuels.

Brazil's climate contradictions got a glaring spotlight Monday, after Ecuador announced voters had decided in a first-of-its-kind referendum to halt oil drilling in the biodiverse Yasuni National Park.

"We hope the Brazilian government will follow Ecuador's example... and leave the oil in the Amazon estuary underground," Marcio Astrini, head of the Climate Observatory, a coalition of environmental groups, said in a statement.

Brazil, home to 60 percent of the Amazon, also faced criticism when it hosted a high-profile summit this month on the world's biggest rainforest, where Lula and other regional leaders ignored calls to adopt Colombian President Gustavo Petro's pledge to stop oil exploration.

Just hours after Ecuador's referendum result was announced -- winning praise from climate campaigners worldwide -- Lula's office sent out a press release from the energy ministry touting his administration's plans to invest 335 billion reais ($69 billion) in the oil and gas sector in the coming years.

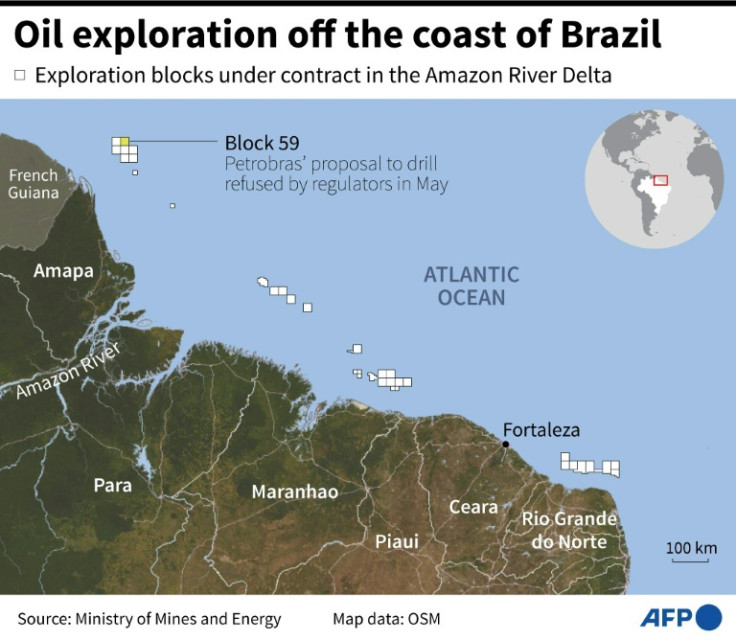

The ministry wants state-run oil company Petrobras to explore offshore block "FZA-M-59," near the estuary where the Amazon river, the rainforest's pulsing aorta, empties into the Atlantic.

The project has triggered a battle within the Lula administration.

After the environmental protection agency, IBAMA, denied Petrobras an exploration license in May, citing a lack of environmental studies, the attorney general's office said Tuesday the studies were "not indispensable" and called for a reconciliation process.

"You can't have a 'reconciliation,' this is about technical facts," fired back respected Environment Minister Marina Silva.

Veteran leftist Lula returned to office in January vowing to protect the Amazon, a vital resource against climate change, after four years of surging destruction under far-right ex-president Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022).

But the 77-year-old ex-metalworker has also said he is "dreaming" of striking oil off northern Brazil.

Guyana, Brazil's small neighbor to the north, has made billions since 2019 drilling in nearby waters, earning the nickname "South America's Dubai."

But the Brazilian project has drawn protests from environmentalists, Indigenous groups and residents of Marajo, the island at the heart of the Amazon estuary.

They say oil drilling could be catastrophic for an environmentally sensitive region known for its mangroves, wildlife, vibrant fishing communities and connection to the rainforest.

"Most of the planet is suffering the consequences of plundering nature for riches," said Indigenous leader Naraguassu, 60, whose people, the Caruana, believe the spot where the Amazon meets the Atlantic is sacred.

"Temperatures are rising. The Earth is telling us something is wrong," she told AFP.

Luis Barbosa of the Marajo Observatory, a local rights group, emphasized that rising sea levels caused by global warming threaten places like the Amazon estuary.

"Continuing to burn fossil fuels puts the very existence of Marajo at risk," he said.

Petrobras says the project "will open an important energy frontier" and contribute to a "sustainable energy transition."

It points out the proposed exploration site is more than 500 kilometers (300 miles) from the mouth of the Amazon, and says it has "robust" containment procedures in case of an oil spill.

But Brazil, the world's eighth-biggest petroleum producer, is already self-sufficient in oil, says Suely Araujo, senior public policy specialist at the Climate Observatory.

"There's simply no reason to insist on exploring for oil in sensitive areas. We're in a climate crisis," she told AFP.

She knows the conflict well: as head of IBAMA, the environmental agency, from 2016 to 2019, Araujo rejected French oil giant Total's bid to explore the same region, on similar grounds.

A member of the transition team that prepared Lula's environmental policy, she says she is glad to see him addressing climate change, but disappointed with the administration's stance on fossil fuels.

"The Lula government's great contradiction is oil," she said.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.