Egypt 2012 Vs. Iran 1979: Superficial Similarities, But Vastly Different Revolutions

ANALYSIS

Egypt and Iran are the most similar of Middle East countries. They are nationalistic, not amalgams of feuding tribes, like the Iraqis, for example. They have civilizations that began thousands of years ago -- that is, they weren't created and then colonialized in modern times out of the ruins of the Ottoman Empire, as Jordan and Lebanon were. And their populations are relatively well educated.

Now, one more thing can be added to this stable of similarities: The political upheaval in Egypt that brought down the 30-plus-year regime of Hosni Mubarak last year appears in some fashion to parallel the Islamic Revolution in Iran thirty-three years ago.

Chiefly, Mubarak, like the former Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was forcibly deposed by a popular revolt that took to the streets to protest decades of repressive control at the hands of a brutal security and secret police network with extraordinary powers to arrest, detain, imprison and torture. Moreover, both Mubarak and the Shah were solidly supported by the U.S., Israel and Western Europe – a scenario that outraged much of the populace and exacerbated festering resentments.

And in the end, Mubarak and the Shah – both of whom were secular modernists – eventually saw their nations (to varying degrees) taken over by Islamist entities determined to write new chapters under the guise of “revolution” and meeting the will of the people.

But in actuality, at that somewhat superficial level is where the parallels between the regime changes in Cairo and Teheran end. As a result, any attempt to predict the near-term future course of Egyptian history based on the way Iran looks today is foolhardy.

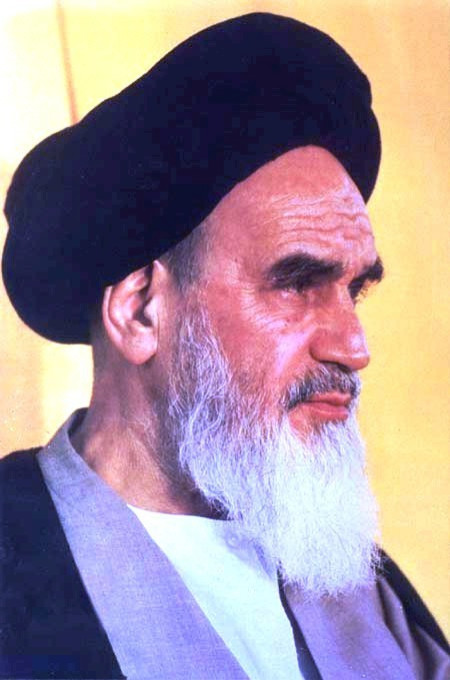

For starters, although opposition to the Shah had been bubbling under the surface for decades in Iran – ever since since the CIA-engineered coup in 1953 deposed the democratically-elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and restored the Shah to power – by the late 1970s, the Islamic mullahs dominated the anti-government Iranian movement. And they had a ready-made, charismatic, well-known, exiled leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who had been living in France since the mid-1960s.

Just a few days after the Shah was forced to flee the country in the face of enormous anger in the streets, fomented in large part by Islamic fundamentalists, Iran’s military collapsed. And within weeks Khomeini returned to a rapturous, overwhelming welcome.

In short order, Khomeini and his mullah allies began a campaign of terror against the Shah's supporters – executing hundreds who didn't escape the country in time. Soon after, a constitution was written that reflected Khomeini's extreme views on behavior, Islamic law and public conduct, including strict dress codes and gender segregation in schools. For a period, even music was banned. And Khomeini was given the titles of Iran's Supreme Leader and Commander-in-Chief.

“The revolutionaries of Ayatollah Khomeini took control of the entire social, political and economic system into their hands,” said Dilshod Achilov, a Middle East expert at East Tennessee State University.

Egypt’s situation could not be more different, chiefly because the military remains a dominant force in the country. The pro-democracy revolutionaries in Egypt have limited power to sponsor major structural changes. (Witness the recent moves made by the Supreme Council of Armed Forces – SCAF -- to limit the powers of civilian politicians and efforts to delay the writing of a new constitution.)

“The main challenge to the Egyptian democracy, of course, is the military elite,” Achilov noted. “[They] have long been accustomed to view themselves as the gatekeepers of the state.”

Moreover, Egypt’s anti-Mubarek opposition has been since the beginning a rag-tag group of competing interests with little of the lopsided dedication to Islamic fundamentalism that existed in Iran. An Islamist did win the recent Presidential election but it is unclear how much power Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood will be given by the military and how much support he will have from the tens of thousands of activists who brought down Mubarek.

One thing is certain: Morsi is no Khomeini, who enjoyed the fanatical devotion of thousands of young revolutionaries, galvanized by the uniting force of Shia Islam. Unlike Khomeini, Morsi has to contend with elements of the former regime – the candidate that he narrowly defeated in the presidential election, Ahmed Shafiq, is a Mubarak minister.

Because of this messy political landscape, the powerful presence of the military and the relatively limited power he has been given, Morsi is compelled to promote democratization (e.g., civil liberties, political rights, rule of law, while curbing widespread corruption) in Egypt. By contrast, Khomeini had complete say over who got elected and which political, social and economic initiatives were undertaken.

“He had the last say, and, if a president fell out of line, Khomeini could force him out of office,” said Jamie Chandler, a political scientist at Hunter College.

Unless extremists somehow stage a violent coup, Egypt’s new government will likely adopt a pro-western populist stance based on secular Islamism.

“Egypt is not a theocratic state and it is highly unlikely that it will become one even with the new Islamic-oriented government,” Achilov added.

Indeed, Morsi's brand of Islam is quite moderate (light years removed from Khomeini's aggressive, fundamentalist beliefs). For that reason, a more apt comparison for Egypt in 2012 is Turkey, not Iran. Turkey is a democratic, secular Islamic nation that is committed to economic prosperity.

Interestingly, both Morsi and Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan have to contend with powerful military elites that must be appeased and kept under control by civilian authorities. Following major reforms enacted by Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party the Turkish military does not pose the kind of threat to Turkey's democracy as the long shadow SCAF casts over Egypt's embryonic republic. (In fact, Erdogan has curbed the military’s power to such a degree that hundreds of active-duty officers are currently facing trial on a number of charges, including plotting to overthrow the state).

Perhaps then that’s the benchmark by which to judge the Egyptian revolution: can Morsi or anyone who follows him politically tamp down the military, a challenge that Khomeini didn’t have to wrestle with.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.