'Elderly' Kepler Spots 'Lonely' Planets Free-Floating In Our Galaxy

KEY POINTS

- The retired Kepler Space Telescope spotted signals of possible rogue planets

- Unlike Earth, these planets are not attached to a host star

- Kepler spotted gravitational microlensing signals even though it was not designed for it

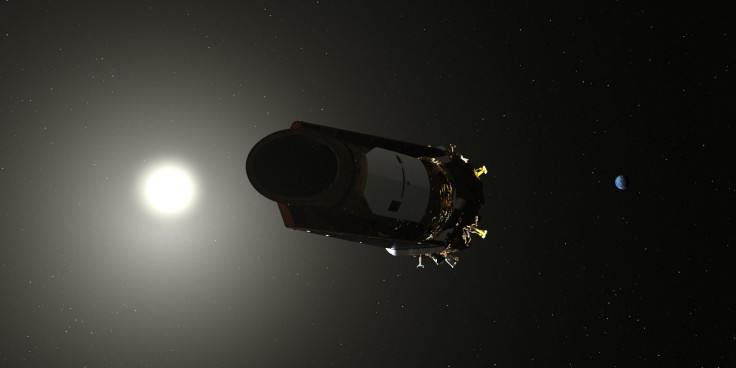

The Kepler Space Telescope has just proved that even an "elderly" telescope with "blurred vision" can help provide valuable scientific information. The retired telescope helped a team of researchers find evidence of a population of rogue planets free-floating in our galaxy.

For a new study, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), researchers used the data obtained by the retired Kepler Space Telescope in 2016 during the K2 mission, RAS said in a news release. During the campaign, Kepler focused on an area with millions of stars close to the center of our galaxy to spot "rare" gravitational microlensing events.

The team spotted a total of 27 short-lived microlensing signals, most of which were previously observed but five of them were new. Among the newly-observed events, four candidates were consistent with that of free-floating planets with masses similar to that of Earth.

Lonely planets could be floating free through the darkness of space, in new research in #MNRAS: https://t.co/IxyKMEgp1H pic.twitter.com/KvUg9Co5aP

— Royal Astronomical Society (@RoyalAstroSoc) July 6, 2021

Free-floating planets, otherwise known as rogue planets, are the ones that are not bound to a host star. It's possible that they were formed around one star but were thrown out from the star system by the gravitational influence of the larger planets.

What is gravitational microlensing?

Albert Einstein predicted microlensing 85 years ago. It essentially happens during chance events when the light of a background star temporarily gets magnified from our viewpoint because of the other objects around it.

An animation from the RAS demonstrates how such events occur.

The method is typically used by astronomers to observe distant stars using closer stars. It's rarely used to spot lensing events caused by planets because they are smaller, so the signals they create aren't as noticeable.

Although the Kepler Mission was specifically used to survey our area of the Milky Way in order to find other planets potentially in the habitable zone, it was not designed to find planets using microlensing or to look at the "extremely dense star fields" in the inner Galaxy, RAS said. So, the researchers had to develop new techniques to look for signals in the Kepler data.

Calling Kepler an "elderly" telescope, study lead Iain McDonald, of the University of Manchester, described the signals as "extremely difficult to find," especially with the telescope's "blurred" vision and since many other objects were in its vision.

"From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it's gone," McDonald said. "It's about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone."

"Whilst Kepler was not designed for crowded-field photometry, the K2C9 data set clearly demonstrates the feasibility of conducting blind space-based microlensing surveys towards the Galactic bulge," the researchers wrote.

According to the scientists, these new candidates can be confirmed by upcoming space missions that are actually optimized for such microlensing signals. The "systematic issues" that affected K2 would be "less significant" then.

"Kepler has achieved what it was never designed to do, in providing further tentative evidence for the existence of a population of Earth-mass, free-floating planets," study co-author Eamonn Kerins, of the University of Manchester. "Now it passes the baton on to other missions that will be designed to find such signals, signals so elusive that Einstein himself thought that they were unlikely ever to be observed."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.