Election 2016: Amid Union Endorsements For Democratic Party, Labor Support Could Be Important For Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders

When the Laborers' International Union of North America endorsed Hillary Clinton on Tuesday, it marked the Democratic presidential front-runner’s 15th major labor union endorsement. It was the third such indication of support for her in the past week, following endorsements from the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Ironworkers union Monday and the powerful Service Employees International Union (SEIU) on Nov. 17. It was also likely a disappointment for her main opponent, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who has historically championed labor causes.

The pile of endorsements marks a departure from 2008, the first time Clinton ran for president, when organized labor was deeply divided between backing her and then-U.S. Sen. Barack Obama. The support of unions, which have since seen membership plummet, typically comes with grassroots financial and volunteer commitments, leaving super PACs to mostly pick up the political funding slack. But in an election where Clinton has been her party's presumptive nominee for months and voters seem to pay little attention to traditional measures, just how much weight do union endorsements still hold?

“Unions have actually gotten more effective at mobilizing members, at getting them to vote,” said Joseph McCartin, a history professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., who leads the university’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. “While unions have seen an erosion in membership, that doesn’t mean there has been an erosion in the power of an endorsement.”

Declining Membership

For much of the last century, unions were extremely powerful in the United States. But a shift toward service-oriented industries that have less union presence combined with a rise in anti-union legislation has resulted in far fewer employees participating in the labor movement.

As large companies tired of dealing with labor strikes, lawmakers have passed legislation that limits collective bargaining and prohibits union membership from being a condition of employment. Over the past four years, even traditionally union-heavy states such as Wisconsin and Indiana have passed laws that significantly curbed union membership.

After the 2012 election, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the percentage of workers in unions fell to 11.3 percent, marking a 97-year low. By 2014, the union membership rate was down to 11.1 percent, according to federal statistics, with the rate among private-sector workers at 6.6 percent, compared with 35.7 percent among public-sector employees.

These numbers have shrunk from 20.1 percent in 1983, the first year for which data was available. In total, the U.S. had 17.7 million union workers in 1983, but even with significant growth in the workforce overall, just 14.6 million employees belonged to a union in 2014.

While membership continues to decline, however, public opinion of unions has fluctuated over the years. After labor unions took particularly large dips in popularity during the 1970s and then during the recession in 2008, Gallup found that 53 percent of Americans approved of them in 2014.

“There have been some developments in the last couple of years that suggest unions are regaining what they may have lost with public perception,” said Benjamin Sachs, a professor of labor law at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “One example of that is the Fight for 15 [movement], which is very popular, as well as the push to increase the minimum wage more broadly. One reason that does so well is it’s on behalf of all low-wage workers as opposed to things that just affect union members.”

Focusing On Grassroots Support

Participating in broader movements can help labor unions gain more traction and build on their own organic, grassroots actions, which experts say may be of growing importance to their political power. While unions have always employed a combination of on-the-ground action and money to support political candidates, the proliferation of super PACs has tipped the funding balance farther in favor of business interests and away from unions.

In 2012 -- the first presidential election after the Citizens United Supreme Court decision that allowed unlimited political expenditures from nonprofit corporations -- the labor sector donated about $618,000 to Obama’s re-election campaign. In contrast, the finance, insurance and real estate sectors gave the president a combined $21 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. So far in the 2015-2016 cycle, labor interest groups have spent about $15 million (mostly on Democratic candidates and liberal groups), compared with $234 million from the finance, insurance and real estate industries.

When candidates like Clinton and Sanders are not struggling for money, unions may have more influence in spreading the politicians’ message to voters in important areas of the country.

“If you look into the whole string of primaries going into Super Tuesday, [unions] can be a real factor in mobilizing in key early states,” said Steve Rosenthal, a longtime Democratic strategist and former political director of the AFL-CIO, an umbrella organization for unions.

This is the kind of support Clinton and Sanders have been vying for all fall, as unions with large membership bases can make a big difference when trying to knock on doors, make phone calls and canvass around the country. The ironworkers’ union that endorsed Clinton on Monday, for example, includes 11 million members. If most, or even a significant portion, of those workers stump for Clinton, she can reach a lot more voters on a personal level than she can with money for a TV ad.

Generating Enthusiasm

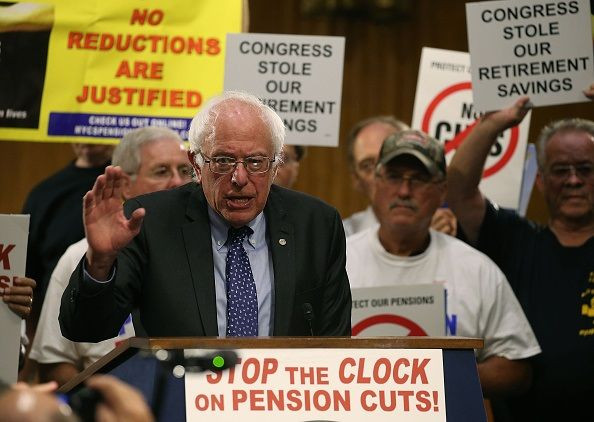

The focus on grassroots support also complicates the tug-of-war for big endorsements in this cycle. While Sanders has received just two major national union endorsements, he has the passionate support of many local unions, as well as defectors who disagree with their national organizations’ support for Clinton.

When SEIU endorsed Clinton last week, many members expressed their dissent.

“Bernie Sanders has an outstanding 35-year record of standing with workers and their unions to improve not only wages and working conditions, but security, economic, health, job security for workers,” said Rand Wilson, a staffer at the union’s Local 888 in Massachusetts and a founder of the grassroots network Labor for Bernie.

Rand said that union workers are excited about Sanders because he supports policies that most closely align with their interests. Clinton and Sanders both generally agree on issues such as opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership and supporting collective bargaining, but Sanders wants a $15 minimum wage and Clinton has said she supports an hourly rate of $12.

“A lot of members usually ignore the decisions of their leadership, it’s not very meaningful to them,” Wilson said. “But what’s interesting this year is how passionate people are about Bernie’s campaign and wanting their unions to get behind him.”

The SEIU endorsement is not the only one to draw controversy. When the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees endorsed Clinton last month, the union’s announcement on Facebook was taken over by hundreds of angry, pro-Sanders commenters. Like many unions that make national endorsements, AFSCME took months to poll its members and invited the Democratic presidential candidates to speak at an event before its executive board made a decision.

“All three of the candidates who sought our endorsement have vocal supporters within our union and our communities. In an organization of 1.6 million members, there will always be room for disagreement, but we operate as a democracy. Six months of feedback, polling, and engagement with members in every corner of the country showed a clear and consistent strong preference for Hillary Clinton from two-thirds of AFSCME members,” an AFSCME official said in a statement.

In an election cycle with so many Republican challengers, labor unions have likely gravitated to Clinton so they will be able to present a strong, united front during the general election next fall. In 2008, when unions split their support between Clinton and Obama, some labor organizers worried the intense primary competition could “dampen enthusiasm” during the general election, the Los Angeles Times reported. That is not something organizers want to see in 2016, when they're faced with such a large and conservative Republican field. But while the union endorsements are important for Clinton, experts say she still has work ahead to make them count.

“To translate the power of an endorsement down to the rank-and-file is not always that easy,” Georgetown University's McCartin said. “Clinton will still need to convince rank-and-file members that she’s going to fight for them. A lot of it will depend on her and what kind of campaign she decides to run.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.