Email From Worker Saying He Saw Malaysian 370 Go Down Only Adds To Mystery

It's been five days since the disappearance of Malaysian 370, and we have as many as three possible locations where it might have occurred. The number of places in Southeast Asia where Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 could have crashed just rose by one on Wednesday, after an email from a New Zealander who works on an oil rig off Vietnam scrambled once again what we know about the flight.

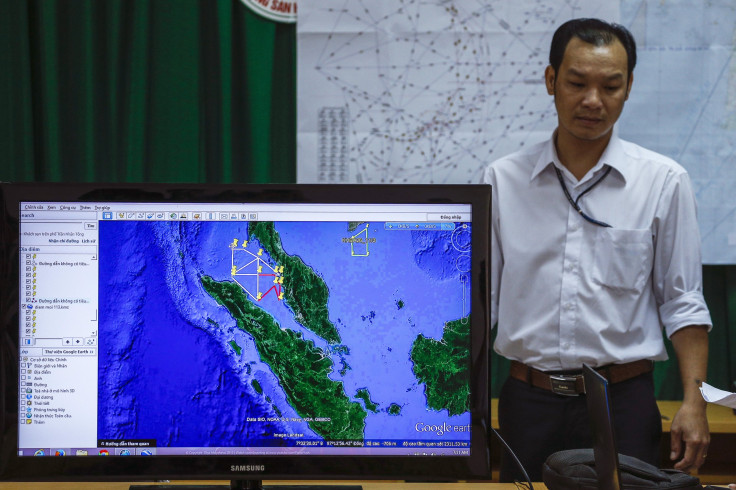

The email that shifted the focus of the search for a third time was sent to his supervisors by Mike McKay, who works on the oil platform Songa Mercur, owned by Norway-based drilling contractor Songa Offshore (STO:SONGO). In a message from Wednesday, published by The Atlantic, McKay said, “I believe I saw the Malaysian Airlines [sic] plane go down. The timing is right.”

U.S.-based ABC News said in a tweet it had spoken to the Japanese company Idemitsu Kosan Co (TYO:5019), which had hired the Songa rig to drill for oil on its behalf, and could confirm the email was legitimate.

What cannot be verified at this time is that what the oil rig worker said he saw was really the missing airplane. The Boeing 777 headed from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing disappeared in the very early hours of Saturday, local time, no later than two hours after takeoff, according to conflicting accounts from the Malaysian government and its military. It had 227 passengers and 12 crew aboard and has not been seen or heard of since.

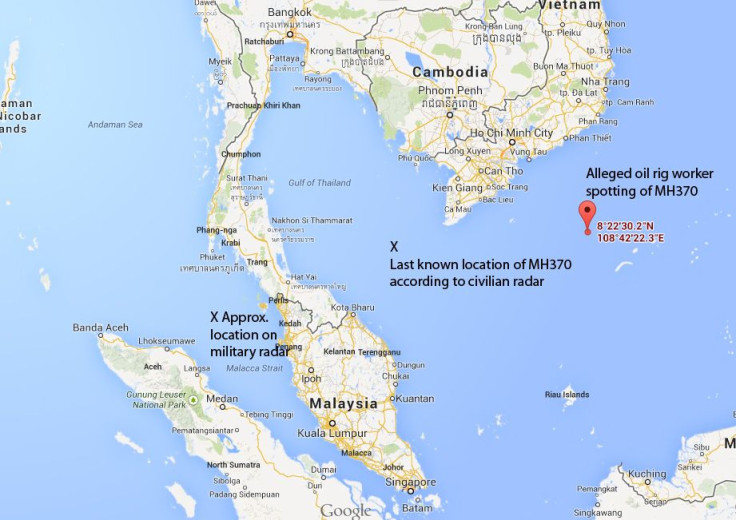

Initial reports citing civilian authorities said the plane had lost radar contact somewhere between Malaysia and Vietnam, over the South China Sea, less than one hour after leaving the Malaysian capital. A search and rescue effort immediately started in the area, involving as many as nine air forces and navies plus private vessels. The hunt has failed to turn up anything besides oil slicks that may or may not be from an airplane.

On Tuesday, a Malaysian newspaper quoted the commanding general of the nation’s air force as saying that the plane had been tracked by military radar up to two hours after takeoff, until a point well to the west of where civilian authorities had said it was. That point was over the Straits of Malacca, on the way to the Indian Ocean, indicating the jet had turned back and was flying due west, not north-northeast toward Beijing. A military source confirmed the statement to Reuters.

Then, later Tuesday, the general retracted his words, saying that the journalist had misunderstood, and the air force could not tell for sure that it had really tracked the missing airplane.

And one day later, the email from the rig worker surfaced. It said the jet had been seen at a location identified by precise coordinates; appeared to be in one piece; was on fire; and was headed 265 to 275 degrees on the compass – or precisely due west. Then, wrote McKay, “the flames went out, still at high altitude.”

The email does not say at what time this occurred, other than saying that “the timing is right.” At this point, while the email has an aura of credibility, it cannot be confirmed that the worker really saw a flaming Boeing 777. Depending on whether one believes the civilian or the military radar tracking, the plane was at 35,000 or 29,000 feet -- and it was night. The moon was half-full at the time, making it a little easier to see, but an observer at sea level would still have had to recognize with certainty a 210 ft (63 m) object more than five miles (9 km) away, at night. Not an easy task.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.