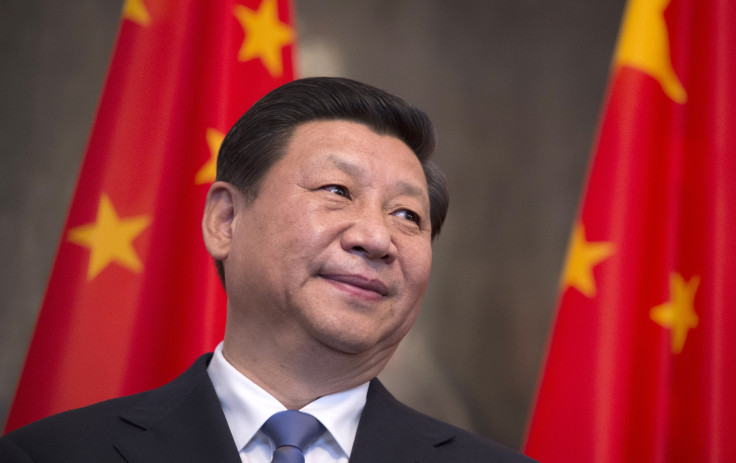

The Enigma Of Xi Jinping: Ahead Of US Visit, China's Tough Leader Beset By Economic And Social Challenges

SHANGHAI -- China’s President Xi Jinping begins his first state visit to the United States fresh from an event which, when it was planned a year ago, looked likely to seal his place as a global statesman and a strongman at home. The recent military parade in Beijing to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of Japan’s wartime occupation of China was tailor-made to highlight the power of the leader of the world's second greatest economic power, a man widely seen as China’s strongest helmsman since the old generation of revolutionary leaders, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Yet despite his aura of control, China’s leader arrives in the U.S. with new questions being asked about his grip on China’s system, and its future direction.

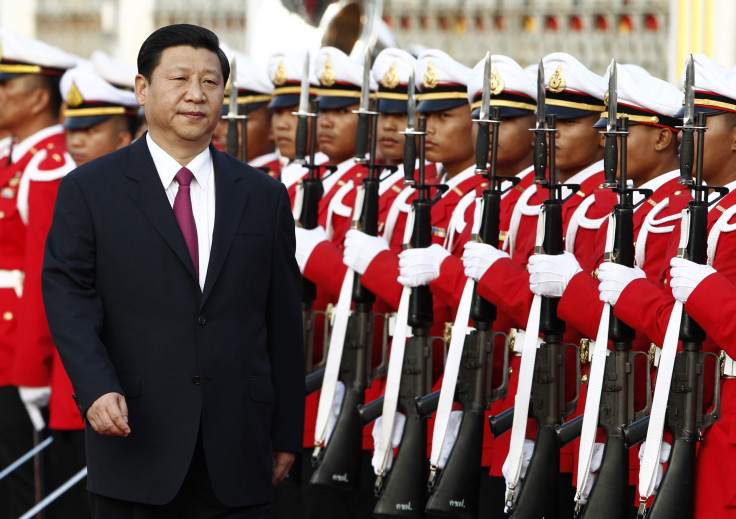

The event in early September was certainly picture perfect: against a pure blue sky and the vermilion walls of the Forbidden City, former home of China’s emperors, the 62-year-old head of state and Communist Party chief first made a somber speech calling on the nations of the world to set aside war and unite for peace. Then, from the open top of a gleaming Red Flag limousine, he inspected China's military, in a seemingly endless parade of highly disciplined troops, the nation's newest tanks, planes and helicopters -- and truck-mounted missiles capable of delivering a nuclear strike on Hawaii or Guam.

It was a reminder both of Xi’s control over China’s powerful military -- whose top leadership he has purged since coming to power in 2012 -- and of the country’s growing international influence. Xi has presided over a more assertive approach to China’s foreign policy than any of his predecessors since the death of Mao in 1976. He has risked the wrath of China’s Southeast Asian neighbors, and the U.S., to reclaim land and build runways on disputed islands in the South China Sea. He has made clear his anger at Japan, which failed to join the parade, and called on it to face up to history. And U.S. officials have also accused China of going to new lengths to hack key U.S. security assets, including, they say, the U.S. federal government computer system, and the data of four million employees.

Domestically too, Xi has often seemed to follow the lead of the guest of honor at the parade, Russian President Vladimir Putin -- by sidelining rivals, and cracking down on lawyers, civil activists, journalists and bloggers -- while pushing through populist policies including a tough environmental law and anti-corruption campaign.

But in recent months China's reputation has suffered, amid concerns about its economy. A dramatic boom and bust on China’s stock markets, coupled with falling exports, and a sudden, still not fully explained decision to devalue the nation’s currency, the yuan (even if only by about 2.8 percent) has caused consternation on global markets in recent months. And foreign investors were further alarmed when the authorities began blaming international hedge funds for causing some of the market turmoil. A series of accidents -- including the sinking of a cruise ship on the Yangtze River, killing more than 400 people -- and a disastrous explosion at a chemical storage facility in Tianjin, which killed 173 people and was followed by a bungled response that alienated many -- have also raised concern at home and abroad about potential challenges to the Chinese economy, and the capacity of its leaders to deal with them.

So while Xi’s state visit to the U.S. “will boost his prestige at a tough time back home,” according to Willy Lam of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, his American hosts may still be asking themselves who the Chinese leader -- who analysts say gives away little of his true feelings -- really is. Is he the powerful reformist technocrat whom some had hoped would parlay his power, once consolidated, to implement real economic and social reforms? Or is he simply a leader with authoritarian tendencies, and a less than solid grip on a complicated and fast-changing nation, which some fear could lead to a growing emphasis on nationalism as the glue holding society together?

What’s not in question is the fact that, in recent years, Xi has been China’s most popular leader since Deng Xiaoping. He swept into office with a new style, looking more relaxed than his predecessors in his open-collared shirts, often accompanied by his wife, Peng Liyuan, a popular singer of military and folk songs who has served to humanize the president, and whose fashion choices frequently go viral on China’s Internet.

“Xi looks more personable, he takes his wife with him -- whereas other leaders would not usually let their families be seen in public,” says Eric Fish, author of a new book, "China’s Millennials," on the nation’s youth. “And his anti-corruption drive has played well with the younger generation, who had been complaining about the problem a lot on social media before he came into office. He’s taken down higher level officials than any leader since Mao.”

Indeed, Xi initially appeared to have largely succeeded in overcoming claims, made in a report by Bloomberg News shortly before he took power in 2012, that members of his own extended family had acquired significant wealth (though there was no suggestion they had done so by anything other than legal means) -- and convinced a sizeable part of the Chinese population that his crackdown on corruption was genuine. Among a raft of senior political and military leaders, it brought down major targets -- known as “tigers” -- including widely disliked former security chief Zhou Yongkang and former army chief General Guo Boxiong.

“I think Xi has a real determination to make the party cleaner and more disciplined,” says Dali L. Yang, professor of political science at the University of Chicago. “He’s said very clearly, if you want to do public service, then stick to that. If you prefer to make money, OK, society will give you the chance to do that -- but don’t go into public service to become rich.”

Yet while Xi’s clean-up of corruption, which had become an endemic problem in the Communist Party during two decades of rapid economic growth, has endeared him to many, some see his accompanying calls for all of society to join his campaign for a more sober morality as out of touch with a generation that has grown up with the greater freedoms of the Internet era, and is more conscious of its own individuality. (Aside from ordering officials to avoid big weddings and banquets, there have also been bans on scantily clad models at auto shows and trade fairs, restrictions on how much cleavage actresses can show on television, and other rules suggesting attempts at promoting a more puritanical lifestyle).

“It’s all about obedience,” says a Chinese businessman, discussing the party’s approach over a drink in a smart Beijing bar. “And I find it hard to accept that.”

Lam, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and author of “Chinese Politics in the Era of Xi Jinping,” agrees that there is “a big question mark over whether young people are willing to be on the receiving end of so much propaganda. All these morality campaigns might be counterproductive.”

Indeed, Lam believes that Xi’s anti-corruption honeymoon could soon be over: “Most Chinese people gave Xi a lot of credit for the campaign at first,” he notes. “But I think the authorities have more or less finished taking down the major ‘tigers’ now -- and people have become a bit more cynical as they realize that most of these big tigers are also Xi’s political enemies.”

The upheavals over the stock market -- and the government’s initial policy of letting it boom, and talking it up in official media, followed by attempts to stop the plunge, which couldn’t prevent it falling 40 percent in a month -- have also left Xi “significantly less popular among ordinary Chinese,” Lam suggests. Even some of those who have done well from China’s economic reforms express concern.

“There’s been too much government intervention [in the market], it didn’t work,” says the Beijing-based businessman, adding anxiously: “And now I’m worried they’ll do more unnecessary things.”

Lam suggests that while Xi will be seeking to emphasize that China remains very much open to business during his meetings with members of the business community in the U.S., the likely upshot of the recent economic challenges is a slower approach to the economic reforms that he has long promised to make -- reforms that many investors believe China urgently needs.

“I think they will learn their lesson about the stock market,” Lam says. “But when China’s leaders face problems, they tend to act cautiously, so I think reforms like lifting restrictions on the transfer of capital out of China may be delayed."

Victor Shih, a specialist in China's political economy and international relations at the University of California, San Diego, agrees that, in challenging times, “'Stability trumps all', as the Chinese saying goes -- I think this is more true today than ever before.”

Some observers have argued that a weaker Chinese leader, faced with a slowing economy, might be more prone to provoking confrontation, raising the potential for clashes between China’s fast-modernizing military, and regional rivals with whom relations have been tense, including U.S. allies such as the Philippines, Taiwan or Japan. The latter has just angered Beijing by passing laws allowing its military to engage in overseas actions as well as simply self-defense, for the first time since World War II.

However, Lam says that a more chastened Xi may need “a foreign policy success” with the U.S. more than before -- making the chances of an accord on cybersecurity, foreign investment in China, or even some form of agreement over the future of the South China Sea, a little more likely on this trip. “Xi is still strong -- no other faction in China can threaten him at the moment,” Lam says, “but we have seen some dents in his armor, and not everyone is happy.”

A serious military confrontation with the U.S. over the South China Sea is the last thing Xi needs at present, Lam adds. “A skirmish would cause panic in China," he says. "It would hit the economy, the stock market might collapse -- and they can’t afford that.” Over the past two years, Lam says, the world has seen a more assertive China flexing its muscles -- without planning to go too far in provoking others.

However, with Beijing warning the U.S. to keep away from the islands it is building on in the South China Sea this year, and also sending its navy on joint exercises with Russia as far as the Mediterranean, some Chinese analysts have nonetheless warned that Beijing is taking a risky approach in abandoning the “low-key” foreign policy approach it has practiced since the era of Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s. And Lam too acknowledges the existence of what he calls a “dangerous element: compared to the eras of [his predecessors] Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin. Under Xi the generals now have a bigger say on national security and foreign policy issues -- and like military leaders in many countries they tend to be more hawkish.”

One Chinese academic, who asked not to be named, also expresses concern that Xi has concentrated power in the hands of himself and a few advisers in a number of “leading groups,” covering issues ranging from economics to security, which operate in parallel to the government. He fears there may be “less and less debate in the leadership: I do hope others can say no to him, can veto decisions, but I don’t know."

And a worry that Xi’s concentration of power could spill over into the realms of the personality cult -- one of his books is said to have sold more than five and a half million copies worldwide, and there are institutes, and even a new app, for the study of his speeches and writings -- has also alarmed some who initially saw him as a modernizer.

In many ways Xi remains something of an enigma -- with some of his policies, such as a sudden campaign against Western ideas in academia, confusing even to his own people, according to Yang at the University of Chicago. It may be hardly surprising, given the apparent contradictions inherent in some of the government’s actions: not only has Xi’s leadership pledged financial reform, then intervened heavily in the stock market, it has also stressed improving the “rule of law,” before overseeing China’s biggest crackdown on civil rights lawyers in two decades. It has promoted a new law against domestic violence -- and then detained young feminists who campaigned in support of the law; similarly, according to human rights groups, it has passed a tough environmental law, yet continued to harass environmental activists. And it has pledged to build an economy based on the Internet while tightening controls on online debate and promoting a tough new cyber law.

Such contradictions may simply reflect official paranoia at public participation in policy implementation -- nothing new in China -- but in a more modern society they worry some observers and investors. And it remains to be seen whether the recent global concern about China’s economic decision-making -- something which appeared to shock the leadership in Beijing, which has repeatedly insisted that nothing has changed and the economy remains in an “appropriate” phase of development -- might lead Xi to realize the value of pushing ahead with faster reforms.

Some observers are still optimistic.

“I do think significant changes are still happening in the development of China’s legal framework, in terms of procedure and openness, for example,” says Yang of the University of Chicago. “It’s not perfect, but substantial reforms have been taking place.”

However, others are less sure. Maya Wang, a researcher on China at Human Rights Watch in Hong Kong, says a raft of laws passed or drafted over the past years -- covering everything from nonprofits to the Internet and national security -- have created a “cage of law,” which is actually designed to restrict the behavior of Chinese citizens. And many observers believe that Xi and those around him see an activist civil society as a serious threat to the party: Xi has repeatedly warned officials of the dangers of surrendering too much of the party’s power, using the collapse of the Soviet Union under reformist leader Mikhail Gorbachev as a warning. He is, therefore, likely to continue to pursue a cautious approach to fundamental reforms -- even if that means leaving himself increasingly out of step with China’s fast-changing society.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.