Ethiopians Vote In Poll Overshadowed By Tigray

Voters in Ethiopia cast ballots Monday in a delayed national election taking place against the backdrop of war and famine in the northern Tigray region and questions over the poll's credibility.

It is the first electoral test for Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, 44, who rose to power in 2018 championing a democratic revival in Africa's second most populous country, and a break from its authoritarian past.

"This election is different," said Milyon Gebregziabher, a 45-year-old travel agent voting in the centre of the capital Addis Ababa. "There are a number of parties to choose from. In the past there was just one, we did not have the luxury of choice."

Abiy, a Nobel Peace laureate who freed political prisoners, welcomed back exiles and ended a long cold war with neighbouring Eritrea before sending troops to confront the dissident leadership of Tigray late last year, has promised this election will be Ethiopia's most competitive in history, free of the repression that marred previous ballots.

But the spectre of famine caused by the ongoing fighting in Tigray, and the failure to stage elections on schedule in around one-fifth of constituencies, means that promise is in doubt.

Polling began in Addis Ababa soon after the expected start time of 6:00 am (0300 GMT) with voters in face masks wrapped in blankets against the pre-dawn chill.

Electoral officials in purple vests sprayed voters' hands with sanitiser before checking their IDs against the register.

"I believe this election will shine a light of democracy on Ethiopia," said Yordanos Berhanu, a 26-year-old accountant at the head of a queue of hundreds.

"As a young Ethiopian, I (have) hope for the future of my country, and believe voting is part of that," she said before slipping her ballot papers into a purple plastic box for the national vote and a light green one for the regional election.

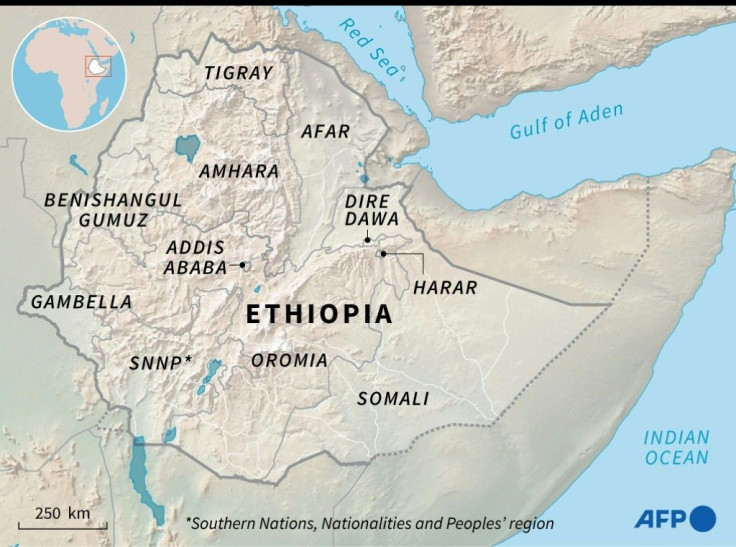

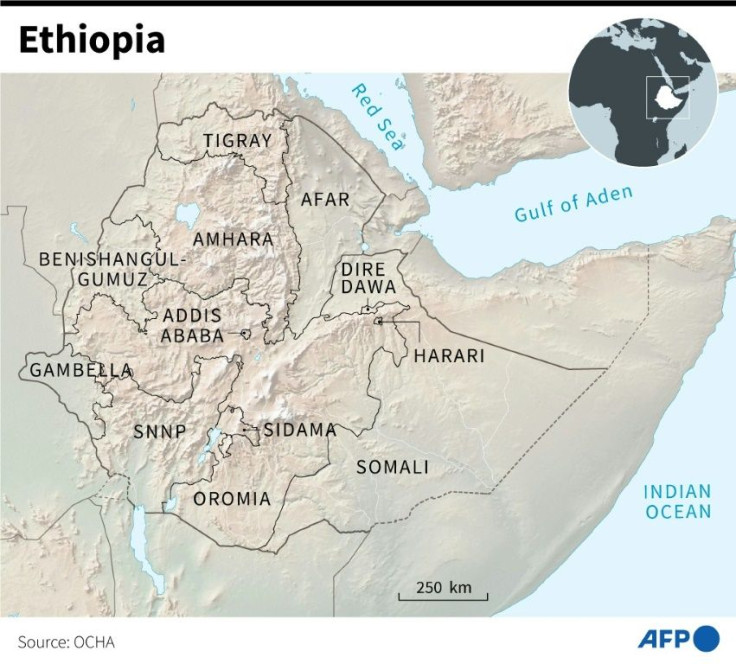

In Bahir Dar, capital of the northwestern Amhara region which neighbours Tigray, voters said peace and economic growth were the priorities.

"No matter who wins, we want peace," said 25-year-old jobseeker Mirkuz Gashaw.

"As a citizen, I hope our country prospers and grows," said first-time voter Etsubdink Sisay, 18, who lined up with her mother.

Once votes are counted, national MPs will elect the prime minister, who is head of government, as well as the president -- a largely ceremonial role.

Abiy's ruling Prosperity Party has fielded the most candidates for national parliamentary races, and is the firm favourite to win a majority and form the next government.

Security was ramped up for the election, with police marching in force in Addis Ababa over the weekend, and reinforcements deployed across the country.

The election was twice delayed -- once for the coronavirus pandemic, and again to allow more time to organise the ballot across a huge nation.

Some 38 million Ethiopians are registered but are polls not going ahead in close to one-fifth of the country's 547 constituencies with some areas were deemed too insecure -- plagued by armed insurgencies and ethnic violence -- while in others logistical setbacks made arranging a vote in time impossible.

A second batch of voting is to take place on September 6 to accommodate many of the districts not taking part Monday.

But there is no election date set for Tigray, where UN agencies say 350,000 people face famine conditions, and atrocities have been documented.

The northernmost region represents 38 seats in national parliament, and has been governed by an interim administration since November, when Abiy sent troops into Tigray, promising a swift campaign to oust its ruling party.

Seven months later the conflict drags on, damaging Abiy's standing as a peacemaker and overshadowing a vote meant to broadcast his country's democratic intent.

In a handful of places where the vote is going ahead Monday, opposition parties are boycotting in protest, reducing some constituencies to a one-horse race.

Even in the best of times, organising smooth elections is a tall order in Ethiopia, a huge country hobbled by poor infrastructure.

Observers have pointed out that logistical support usually comes from the military, which is largely tied up Tigray, leaving organisers short on manpower.

Concerns about credibility have been raised, with traditional ally the United States warning that excluding so many voters risked confidence in the process.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.