Europe's Produce At Stake In Spain's Water War

Spanish farmer Juan Francisco Abellaneda's salads and watermelons fill the shelves of European supermarkets winter and summer. But maybe not for much longer.

The tap that turned the arid semi-desert of southeastern Spain into Europe's market garden may be about to be turned off, threatening the intensive farms that feed much of the continent.

Spain is the EU's biggest producer of fruit and vegetables and almost half of its exports are grown by farmers like Abellaneda, the crops irrigated by huge transfers of water from the River Tagus hundreds of kilometres (miles) to the north.

But with climate change hitting Spain hard, and three-quarters of the country at risk of desertification, the government has decided to limit the flow of the dwindling waters of the Tagus to the southeastern Levante.

The level of the Iberian peninsula's longest river has been dropping dangerously, to the point that in some places it is possible to cross its dried-up bed by foot in summer.

Just like Egypt's shrinking Nile and the Tigris in Iraq, the right to draw on the waters of the Tagus -- which crosses into Portugal before flowing into the Atlantic -- has become a political hot potato.

The debate is getting even more heated in the run up to regional elections later this month, with the intensive agriculture that is a pillar of the Spanish economy called into question.

"We need the water (from the Tagus). If they take it from us, it will be nothing but a desert here," said Abellaneda.

The 47-year-old cast an anxious eye over the dusty drills of broccoli growing on his 300 hectares (740 acres) near Murcia.

Despite another abnormally hot and dry spring, the farm he and his brothers run is thriving, exporting 3,000 tonnes of fruit and vegetables a year.

In his father and grandfather's time, Murcia was one of the poorest parts of Spain, a land of subsistence farmers. Greenhouses and hi-tech storage depots now stretch to the horizon.

"If they do not bring us the water, what are we going to live on?" asked Abellaneda, a founder member of the Deilor cooperative which employs 700 people.

He does not want to turn the clock back and fears widespread job losses if they lose water.

"The region is one of the most arid" in Spain, said Domingo Baeza, professor of river ecology at the Autonomous University of Madrid, with not enough water of its own for its intensive agriculture.

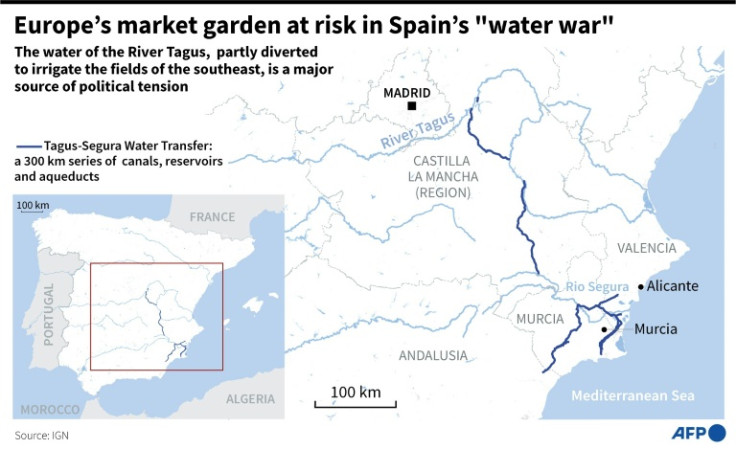

To make the bone-dry southeast bloom, Spain began building the gigantic Tagus-Segura Water Transfer project under the dictator General Franco in 1960. It took nearly 20 years to complete its 300 kilometres of canals, tunnels, aqueducts and reservoirs, bringing billions of litres of water from the Tagus south into the Segura basin between Murcia and Andalusia.

Once hailed as a model in handling drought, it is now accused of making them worse.

It also made the Levante region -- which includes the dry provinces of Murcia, Alicante and Almeria -- Europe's biggest horticultural hotspot, employing 100,000 people in businesses turning over three billion euros ($3.3 billion) a year.

But today "the Tagus is suffering", said Baeza. "It is degraded in numerous places... because we have far outstripped its capacity (with) uncontrolled expansion of the land it irrigates."

Since the Transfer project was built, Spain's average temperature has shot up by 1.3 degrees Centigrade (more than two degrees Fahrenheit), according to the Spanish meteorological service.

The flow of the Tagus has dropped 12 percent over the same period and could plummet by up to 40 percent by 2050, the Spanish government estimates.

Extreme heatwaves over the last few years, sometimes very early in the year -- with temperature records again broken last week -- have dried up rivers and reservoirs and have led to water cuts.

"Global warming has changed things," said Julio Barea of Greenpeace. The Transfer "no longer works" for Spain. "The Tagus needs the water (it is losing to farms in the southeast) to survive," he insisted.

In the central Castile-La Mancha region, where the Tagus' water is syphoned away south, the effects of losing so much water have been visible for years.

"Our land has been sacrificed" for the farmers of the Levante, declared Borja Castro, Socialist mayor of Alcocer, a village near the Entrepenas and Buendia reservoirs, whose water is pumped to the southeast.

Known as the "Sea of Castile" for the artificial lakes that were created by the damming of the Tagus in the 1950s, it used to attract lots of tourists who would come for the weekend to swim, boat and eat in its restaurants.

"It was really lively," recalled Borja's father, Carlos Castro, 65, pointing to the ruins of a cafe near a spot where he would come to swim as a teenager. Now "it's like a desert," he sighed.

The beaches where tourists once lounged have disappeared with the lake water now several dozen metres below where it was.

"Everything stopped when the damned water transfers started," said mayor Castro, who wants them to be stopped completely. "With our water went businesses, jobs and a part of our population.

"They turned the Levante into the garden of Europe, but with water that came from somewhere else. It's madness."

Madrid wants to reduce the water transfers by a third -- except in times of abundant rainfall -- to bring the Tagus's level up.

But without that water, the southeast "will not be able to maintain modern and competitive agriculture," which could put Europe's food security at risk, warned Alfonso Galvez, a head of the farmers' union, Asaja.

The cut could lead to 12,200 hectares of arable land being abandoned, claimed the SCRATS farmers lobby group. The economic cost would also be colossal, it argued, up to 137 million euros a year, with 15,000 jobs lost.

The political battle over the water in the lead-up to this month's elections has created some strange bedfellows.

The Socialist-held region of Valencia in the east has allied itself with Murcia, run by the conservatives of the Popular Party, to try to stop any cuts. Socialist Castile-La Mancha, meanwhile, is backing the government's decree with the help of local right-wingers.

The left-wing government of Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez said it has no choice but to cut the flow to come into line with rulings from Spain's supreme court and EU environmental rules, which demand protection plans for water basins.

Minister for Ecological Transition Teresa Ribera said the decision was based on "the best scientific knowledge possible", and has promised more money to develop other sources of water.

The government is keen on desalination, which is already going on the Levante, but on a relatively small scale.

But many farmers are not convinced. Galvez said desalinated water lacks nutrients and has "a big environmental impact because "you need lots of electricity to make it" as well as its harmful effects on the marine ecosystem.

The conservative head of the Murcia region, Fernando Lopez Miras, is equally sceptical. He said the costs were prohibitive -- three to four times more than transporting the water from the Tagus. "They are talking about a price of around 1.4 euros a litre. That's the price of petrol!"

The farmers have a right to the water, he argued, because the constitution decreed that "Spain's water belongs to all Spaniards". Desalination plants were at best a help, not "an alternative" water source.

For environmentalists, Spain's whole agricultural model has to be rethought. "More than 80 percent of freshwater in Spain is used by agriculture... it's just not tenable," said Barea of Greenpeace.

There has to be a drastic reduction in the amount of land given over to intensive farming if Spain is to avoid disaster, he said. "Spain cannot be the garden of Europe if our water is getting more and more scarce."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.