Exoplanets Hidden By Starlight Glare Could Be Revealed By Chemical Analysis

Astronomers have discovered thousands of planets beyond the boundaries of our solar system, with many sitting in the potentially habitable or “Goldilocks” zone — just at the right distance from their host star to support liquid water and possibly an atmosphere.

The discovery of these worlds is a crucial first step to find life beyond Earth, but the next step requires direct observation and imaging, which has not been possible in most of the cases. The dazzling luminosity from distant stars is so much that the planet orbiting around remains invisible and only those sitting far from their host star can be seen, thanks to the sophisticated ground and space-based telescopes.

As this poses a major threat to the ongoing work, researchers from the University of Geneva have developed a new method as part of which certain molecules are traced in the atmosphere of a planet to enable its direct observation.

"By focusing on molecules present only on the studied exoplanet that are absent from its host star, our technique would effectively 'erase' the star, leaving only the exoplanet," Jens Hoeijmakers, the lead author of the latest study, said in a statement. The researchers proved the theory after testing it on the images — taken by ESO’s SINFONI instrument — of a star named Beta Pictoris.

Though it is already well established that the star is orbited by a giant planet called Beta Pictoris b, the group wanted to see if the novel technique can make the distant world visible. So, they looked into the spectral information in each image.

They analyzed the spectrum of light received by every pixel in the photographs and compared that with the spectrum relating to molecules absent from the star. The idea was to find a correlation indicating the presence of those elements in the atmosphere of the planet and that’s exactly what happened.

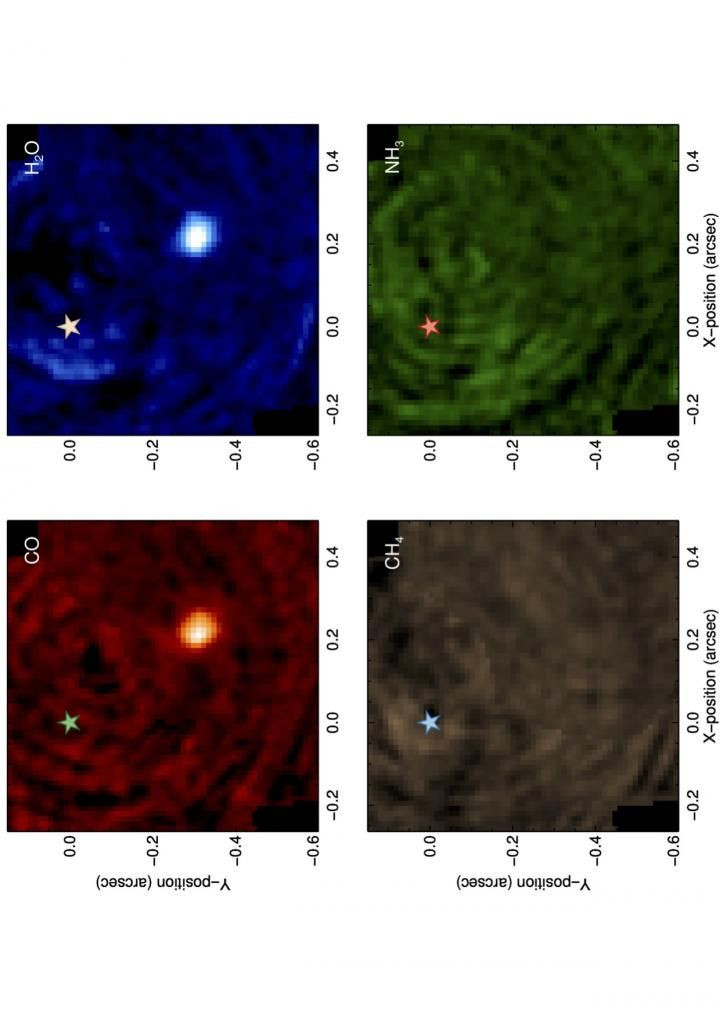

When the group looked for signs of water (H2O) and carbon monoxide (CO), they found Beta Pictoris b became perfectly visible, but when they compared the data in the image with spectral signature of methane and ammonia, the planet stayed invisible.

The star, on the other hand, remained completely invisible in all the four cases because its extreme levels of heat would have destroyed the four elements. This, as the researchers hoped, indicated that the atmosphere of the planet contains two of the four elements missing from the star – water and carbon monoxide – and helped with the observation process.

Among other things, the detection of molecules also serves a thermometer indicating the temperatures prevailing on the world in question. As the group described, the absence of ammonia and methane suggests the temperature on the planet would be around 1,700 degrees, which is high enough to keep the two elements from existing.

"This technique is only in its infancy," Hoeijmakers said of the new method. "It should change the way planets and their atmospheres are characterized.”

The study, titled “Medium-resolution integral-field spectroscopy for high-contrast exoplanet imaging: Molecule maps of the beta Pictoris system with SINFONI,” was published June 11 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.