Explainer-The Fed's 'QT' Plan: Then And Now

The Federal Reserve on Wednesday signaled it will likely start culling assets from its $9 trillion balance sheet at its meeting in early May and will do so at nearly twice the pace it did in its previous "quantitative tightening" exercise as it confronts inflation running at a four-decade high.

Minutes from the central bank's meeting last month, released Wednesday, showed policymakers were presented a range of options for reducing the size of its balance sheet. That stash of assets has roughly doubled in size during the coronavirus pandemic as the Fed used purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities to smooth market functioning and augment the effects of its interest rates cuts.

Here's a rundown of what appears to be in the cards and how it differs from the 2017-2019 "QT" period.

EARLIER START

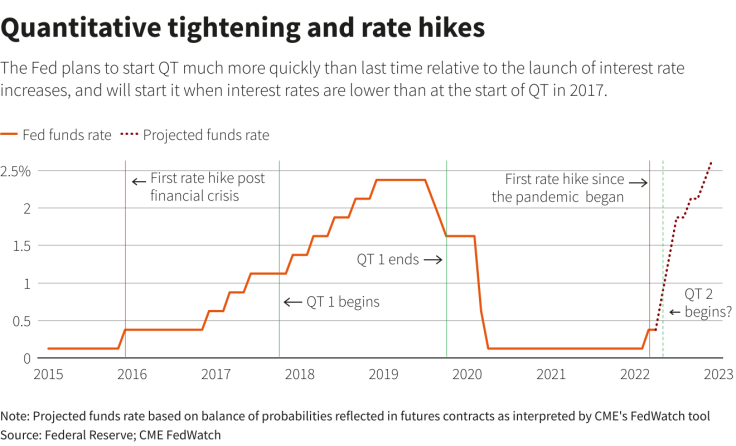

The Fed appears poised to kick off this QT round just one meeting after lifting its benchmark short-term interest rate for the first time since 2018.

Last time, the launch of QT in the fall of 2017 occurred nearly two years after its first rate hike, which took place in December 2015.

This time's onset of QT is also earlier relative to where the Fed will be in the overall tightening process. If rate futures are a guide, the Fed will lift its target rate to 0.75-1.00% in May at the same time it kicks off QT. Last time, QT did not begin until rates had reached 1.00-1.25%.

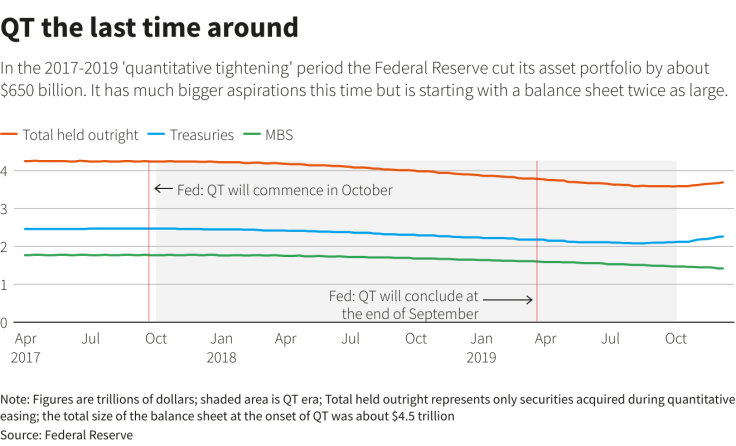

(Graphic: QT the last time around -

)

LARGER CAPS

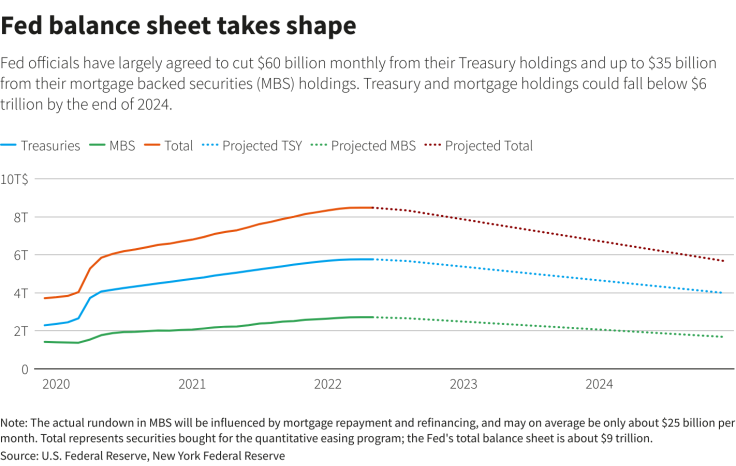

Fed officials "generally agreed" on a plan to cut about $95 billion a month from its holdings, split between $60 billion of Treasuries and $35 billion of MBS.

That is roughly double the maximum pace of $50 billion a month targeted in the 2017-2019 cycle. Back then, the split was $30 billion of Treasuries and $20 billion of MBS.

FASTER RAMP-UP

In the last cycle, it took a full year for the Fed to reach its maximum reduction rate of $50 billion a month. It started with $10 billion a month ($6 billion Treasuries/$4 billion MBS) and increased that by $10 billion a quarter until it reached its maximum rate in the fall of 2018.

This time, it will go from zero to $95 billion in the space of three months ... "or modestly longer if market conditions warrant." The minutes did not spell out precisely how the caps would be "phased in," a detail likely to be set out at the May 3-4 Federal Open Market Committee meeting that is seen launching the process.

BIGGER BALANCE SHEET, BIGGER SHRINKAGE

When the Fed kicked off its first-ever QT undertaking, its total balance sheet was around $4.5 trillion in size. In nearly two years of QT, it managed to bring that down by about $650 billion to a bit over $3.8 trillion before it brought the program to a stop.

This time, the annualized monthly rate of reduction works out to more than $1.1 trillion a year in balance sheet roll-offs. That means it will likely surpass the total of the entire 2017-2019 QT cycle by the end of this year or early 2023. Many economists see officials targeting about $3 trillion in total balance sheet shrinkage over a three-year span.

(Graphic: Fed balance sheet takes shape -

)

(Graphic: Quantitative tightening and rate hikes -

)

DIFFERENT TREASURIES MIX

The Fed's Treasuries portfolio is shorter in maturity this time than in the previous QT round by about two years, according to New York Fed data. That is in part owing to the substantial purchases of T-bills, particularly early on in the crisis, to help restore market stability.

The minutes showed officials are eyeing redemptions of Treasury bills, which mature in a year or less, when the redemption of coupon securities, which are notes and bonds with maturities greater than one year, are below the cap. T-bills are highly valued by private investors and reducing the Fed's stock of them would facilitate more issuance of them by the U.S. Treasury.

In addition, officials generally don't view T-bills as a needed part of their holdings required to ensure an ample supply of reserves for the banking system under their current operating framework.

SELL THOSE PESKY MORTGAGE BONDS?

The minutes showed officials expect redemptions of MBS to run below the $35 billion a month cap. That is because U.S. mortgage interest rates have already risen substantially, which has slowed the rate of "prepayments" that typically occur when rates are low and homeowners are enticed to refinance their existing loans. That triggers a loan payoff and shortens the maturity of a mortgage bond. Conversely, when rates rise, fewer bonds will mature each month.

Officials "generally agreed," however, that it would be appropriate to consider outright sales of MBS "after balance sheet run off was well underway to enable suitable progress toward a longer-run ... portfolio composed primarily of Treasury securities."

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.