Exposure To Common Parasite In Undercooked Meat Linked To Brain Cancer Risk: Study

KEY POINTS

- T. gondii is a common parasite that can be found in the environment

- The parasite is also found in undercooked meat

- Glioma can be fatal but it is still considered a rare cancer

Can a parasite lead to brain cancer? The researchers of a new study found evidence that people with antibodies for a parasite commonly found in undercooked meat could be more likely to develop a fatal type of brain cancer.

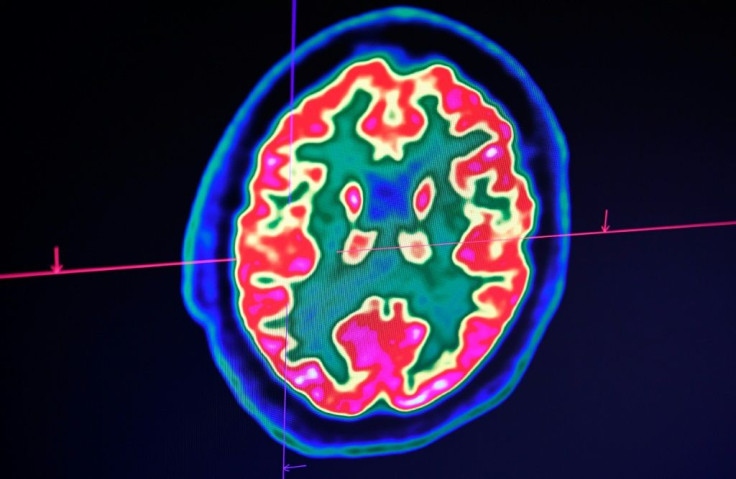

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) is a common parasite that can infect most warm-blooded species including humans, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said. According to the researchers of a new study, published in the International Journal of Cancer, these parasites can also lead to the formation of cysts in the brain.

With past studies showing evidence linking to T. gondii and gliomas, a rare but fatal cancer, the researchers of a new study sought to find a link between T. gondii infections and the risk for developing glioma.

Brain Cancer Risk

For their study, the researchers looked for the presence of T. gondii antibodies in the blood of 111 people enrolled in the American Cancer Society's Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II) Nutrition Cohort and 646 people in the Norwegian Cancer Registry's Janus Serum Bank (Janus).

The blood samples were taken years prior to any glioma diagnoses, and the researchers found that in both groups, the people who eventually developed gliomas were more likely to have T. gondii antibodies compared to the people who didn't get glioma.

Having the T. gondii antibodies suggests that a person was previously infected with the parasite.

The link was made in both groups even if their age groups were vastly different, the American Cancer Society statement explained. The CPS-II group had a 70-year-old average and the Janus group comprised of a 40-year-old average when the blood samples were taken.

"In both cohorts, a suggestive increase in glioma risk was observed among those infected with T. gondii, particularly among participants with high antibody titers specific to the sag‐1 antigen," the researchers wrote. "Our findings provide the first prospective evidence of an association between T. gondii infection and risk of glioma."

Simply put, the findings of the study suggest a higher glioma risk among people who have been exposed to T. gondii. However, the researchers clarify that having been infected with T. gondii doesn't automatically mean that someone will have glioma.

"This does not mean that T. gondii definitely causes glioma in all situations," study lead James Hodge, JD, MPH said in the American Cancer Society statement. "Some people with glioma have no T. gondii antibodies, and vice versa."

Anna Coghill, Ph.D., who co-led the study, further noted that the risk of being diagnosed with glioma remains to be low. According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), gliomas develop in about 6.6 per 100,000 people per year.

But if further studies can prove a link between the parasite infection and gliomas, then the efforts to prevent T. gondii could also be beneficial to prevent the occurrence of gliomas, which comprise 80% of malignant brain tumors and have a five-year survival rate of just 5%.

Preventing T. gondii Infection

Even without the risk of developing gliomas, people should avoid getting infected with pathogens such as toxoplasma. To prevent the risk of T. gondii infections from food, the CDC recommends food safety guidelines including cooking food at the right temperatures, washing fruits and vegetables thoroughly before eating, washing food preparation surfaces and the hands properly, and not drinking unpasteurized goat's milk.

T. gondii may also be contracted from the environment, so safety measures such as not drinking untreated water, not feeding pet cats with raw or under-cooked meats, and wearing gloves while gardening are also important.

These measures are particularly important for people who are pregnant or immunocompromised.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.