Extinct Whale Ancestors Did Not Have Specialized Hearing, It Was Similar To Terrestrial Animals

Known for a keen sense of hearing and the complex range of sounds they can produce, whales rely on audio communication heavily as they cover long distances underwater. From the infrasonic frequencies (below human hearing) of baleen whales to the ultrasonic frequencies (above human hearing) used by toothed whales, the vocal and hearing range of whales is impressive, but it wasn’t always so.

Research published Thursday shows — using fossil evidence from two extinct whale ancestors — that the specialization of hearing in whales evolved only after they became fully aquatic animals like the extant species today, as opposed to their ancestors that lived both on land and in water. The hearing of protocetes — one of the extinct subgroups within the cetacean family, which includes modern whales, dolphins and porpoises — was similar to terrestrial animals.

Read: Whales Became Giants Recently, In Evolutionary Terms

Maeva Orliac of CNRS and Université de Montpellier in France and her colleague Mickaël Mourlam studied fossil remains of 45-million-year-old protocetids found in marine deposits in Togo, West Africa. Specifically, researchers studied the bony labyrinth — a hollow cavity that would have housed the hearing organ — in two early whale species, using micro-CT scans. They discovered the extreme hearing abilities of whales derived from a “mid-frequency ancestral ear.”

“We found that the cochlea of protocetes was distinct from that of extant whales and dolphins and that they had hearing capacities close to those of their terrestrial relatives,” Orliac said in a statement Thursday. These relatives were ungulates — like ancient pigs, camels and hippopotamuses — who shared a common ancestor with whales.

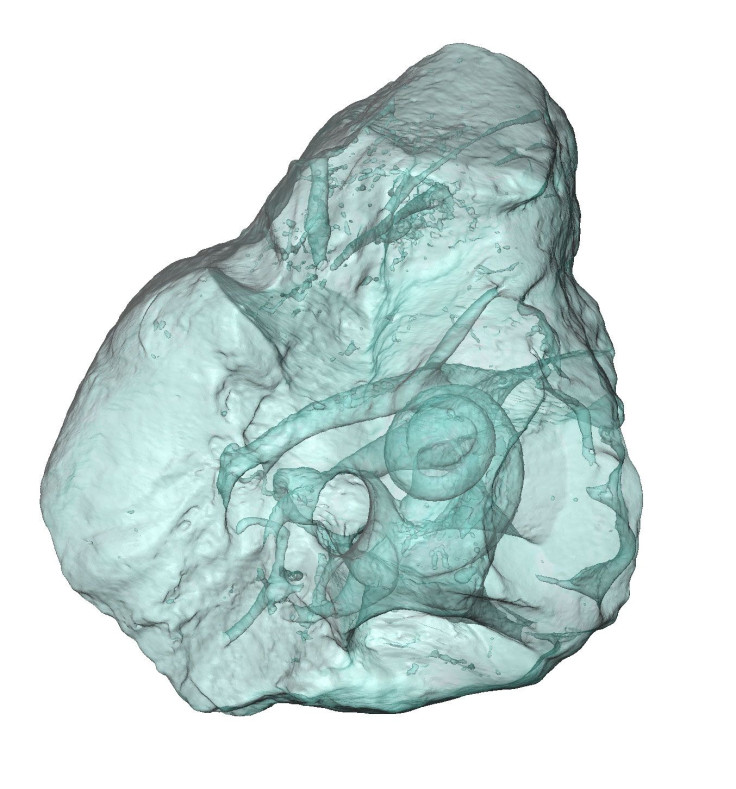

“Based on the scans provided by the scanner, we could extract a virtual mold of the hollow cavity that used to contain the hearing organ when the animal was alive. This process was long and difficult because this cavity was filled with sediments and partly recrystallized and because the petrosal bone in cetaceans is particularly thick and dense, which lowers the quality of the images and sometimes impedes analyzing them,” Orliac said in the statement.

The petrosal bone protects the organs of hearing and balance. Analysis of its internal cavities suggests whales developed their specialized hearing capabilities only after they left land completely, to live in the world’s oceans. The finding shows an evolutionary timeline for whales that is more complicated than previously described, according to the researchers, and added that study these early cetaceans was important to get an accurate picture of how these marine mammals evolved.

Based on dental remains, Orliac and Mourlam have described two of the three extinct species found in Togo. The researchers will return to the country again in December, hoping to find a specimen of the third species and explore its ear.

The research was published in the journal Current Biology under the title “Infrasonic and Ultrasonic Hearing Evolved after the Emergence of Modern Whales.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.