FAA Pilot Fatigue Rule is a ‘Landmark Safety Achievement’

Nearly three years after Colgan Air Flight 3407 fell from the sky near Buffalo, New York, killing 50 people, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) announced Wednesday it had finalized a long-awaited regulation to prevent dangerous pilot fatigue, calling it a landmark safety achievement.

The FAA policy was unveiled Wednesday following extended delays and missed deadlines due to industry opposition over costs and scheduling.

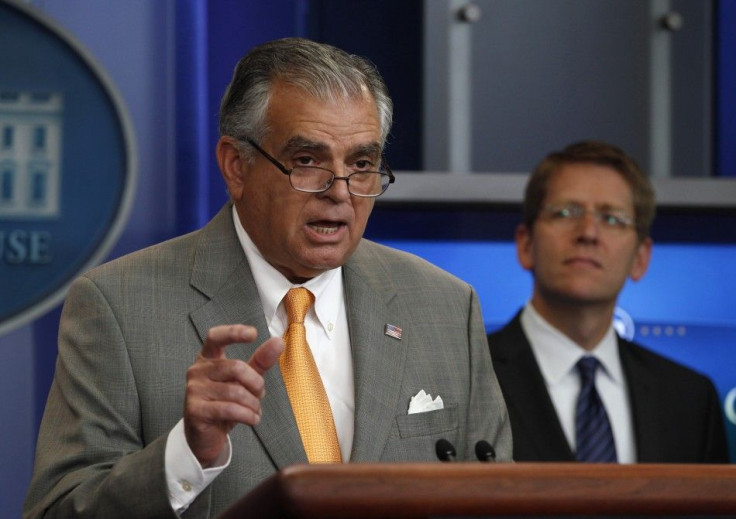

This new rule raises the safety bar to prevent fatigue, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood said, noting that the Colgan crash was his most difficult day in office.

The families of Continental Flight 3407 (operated by Colgan Air) had a personal teleconference with the FAA prior to the announcement.

While they see the new regulation as a step in the right direction, many are eager to see the actual wording.

We want to take a careful look to make sure there's nothing lurking in the rules, Scott Maurer told the International Business Times. Sometimes the devil is in the detail. We need to digest the intricacies as they were explained to us and see how this will all play out.

Maurer is, perhaps, the most outspoken representative of the victims' families. He lost his daughter Lorin on the Colgan Air flight and has been to Washington over 40 times since to fight for change in the airline industry. His son Chris manages the group's Web site, 3407memorial.com.

The Families of Flight 3407 is a grassroots advocacy group for aviation safety.

The FAA recognizes us and we have periodic meetings with them on updates to the rules, Maurer said.

The new rules, announced Wednesday, replace outdated requirements that critics like the Families of Flight 3407 argued did not address the basic business demands of present-day flying and the physical toll of a long day's work. The updated rules offer longer rest periods before pilots report for duty and tighter restrictions on how many hours they can fly per week or month.

Existing rules dating back to the 1960s were littered with loopholes. For instance, between overnight shifts of up to 16 hours, the eight hours of rest could include showering, eating, and getting to and from a hotel. Carriers could even extend the workday if a pilot was flying an empty plane.

Now, there will be cumulative rest times. Pilots must have 30 consecutive hours of rest each week, which is a 25% increase over current standards.

LaHood said the changes were based on the latest scientific sleep research. For the first time ever, pilots will be required to have at least a 10-hour rest period before getting behind the controls to include eight hours of uninterrupted sleep. This exceeds the minimum nine-hour daily rest period proposed by the Federal Aviation Administration in 2010.

Based on sleep science studies, the new rules actually increase the maximum scheduled flight hours for pilots to nine hours per day -- up from eight -- as long as the flights aren't concentrated late at night or early in the morning.

For pilots working for regional airlines (like Colgan) with often grueling schedules, the regulations establish a sliding scale of maximum consecutive work hours that is below the current limits.

READ ALSO: Who's Flying Your Plane?

The process of developing the rules pitted pilots, who advocated greater rest for safety, against airlines, which argued that limiting flight times would raise costs.

Another dispute arose over whether to apply the same rules to cargo pilots. The FAA decided against it due to the cost to that industry; however LaHood said he would invite cargo executives to his office in 2012 to urge them to voluntarily adopt the changes.

On Wednesday, the transportation secretary acknowledged that instituting the rule took too long, but he added that officials needed to consult with broad segments of the industry and wanted to make sure they got it right.

The National Transportation Safety Board has pushed for safety enhancements to reduce pilot fatigue for decades. Though the board didn't blame fatigue as a cause for the Colgan crash in New York, investigators listening to black box cockpit voice recordings heard what they believed were yawns and the board found that neither pilot slept in a bed the night before the accident.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.