'Far From Fragile': The Battering Rams Of Wheelchair Rugby

The battered round wheels collide like Viking shields, as the combatants of wheelchair rugby dodge, battle, and score in a sport that players say upends preconceptions about disability.

"It's a sport that breaks stereotypes, where we push beyond our limits," said Christophe Salegui, 35, a member of the French team competing at the Tokyo Paralympics.

Originally known as "murderball," the sport has a reputation for tough confrontations, with players mercilessly battering opponents to keep them from landing a point.

"It's definitely one of the sports that gets people interested because of the weird nature of it, the collision and the contacts," acknowledged Britain's Stuart Robinson.

Collisions are often so forceful that wheelchairs lift partly off the ground or topple over altogether, with staff helping hoist players back upright.

But athletes say there's simply nothing better.

"I love the speed, the aggression, the competitiveness, the impacts, the camaraderie," said Zak Madell, one of Canada's top players.

And the rough and tumble nature of the sport helps undercut ideas about people with disabilities, he said.

"I think when you just watch it proves that we are far from fragile, and not afraid to go there and knock around and beat up on each other a little bit," Madell told AFP.

Despite the name, the sport differs in various ways from rugby: the ball is round rather than oval and can be passed forward, and it's played indoors on a court rather than an outdoors pitch.

Attackers have just 12 seconds to get the ball across the court's central line and 40 seconds to score a try. Failure to do so in the time means the ball switches sides.

The fast-paced game, invented in Canada in the 1970s, is much more than just brute force though, said Salegui.

"It's super strategic," he told AFP. "It's very technical and tactical."

Four players are on court at any one time, and each is categorised with a certain number of points according to their disability, ranging from 0.5 points for a more severe impairment to 3.5 points.

Each team cannot exceed more than eight points between the players on court, although the figure rises to 8.5 if they bring on a female player.

But while the sport is mixed, men continue to dominate and some teams in Tokyo -- including France -- don't have a single female player.

"It's a relatively new sport in France, so there are not that many players," French team coach Olivier Cusin said.

"There are only about a dozen women who play wheelchair rugby in France, but to make the highest levels is a lot of work and for the moment we haven't found that rare pearl. But we're looking!"

At the Tokyo Games, defending champions Australia are bidding for a record third consecutive gold, coming back from a shock defeat by debutants Denmark in their opening fixture.

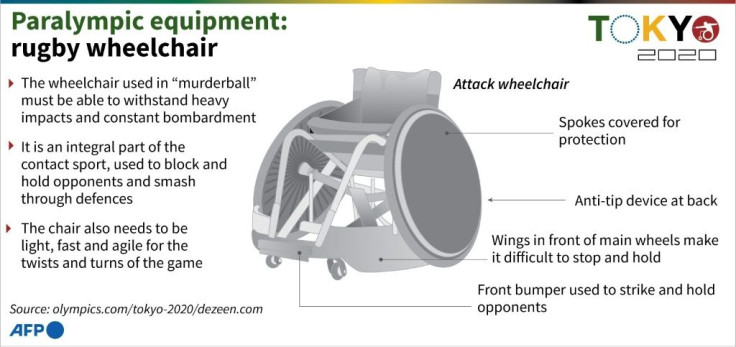

The sport's players are divided between attack and defence, with chairs adapted to their roles.

"Offensive" chairs feature rounded front edges to help players slip past opponents, and wider wheels that help attackers power forward with speed.

"Defensive" chairs by contrast are reinforced with a grid at the front to help blunt attacks.

And it's their chairs, rather than their bodies, that take the brunt of the contact, players say.

"A lot of people kind of protect themselves when they're going to fall. A lot of the hits are taken by the chairs," said Britain's Robinson.

"Relatively serious injuries are very rare," adds Cusin, who says in 11 years as national team coach in the sport he's yet to see a player get seriously hurt.

Specialised mechanics are on hand to keep the chairs in top shape and patch them up after clashes.

"This one is twisted, it's bent there," explained France's mechanic Adrien Corompt, gesturing to a battered specimen belonging to the team, on which his son Christophe plays.

"Bumps and bangs. But that's the sport."

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.