The FBI Now Has The Largest Biometric Database In The World. Will It Lead To More Surveillance?

The story of how the FBI finally tracked down notorious fugitive Lynn Cozart, using its brand-new, $1 billion facial recognition system, seems tailor-made to disarm even the staunchest of skeptics.

Cozart, a former security guard in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, was convicted of deviant sexual intercourse in 1996. According to court filings, he had molested his three juvenile children, two girls and one boy, from 1984 through 1994. It wasn’t until May 11, 1995, that the children’s mother came forward and told the Pennsylvania State Police what Cozart had been doing. He was convicted, but he failed to show up for his sentencing hearing in April 1996. Federal agents raided his home, interviewed family members and released photos of the man to the general public.

Their efforts failed. Months, then years, passed. In August 2006, the Cozart case was featured in "America’s Most Wanted," the national television program, under a segment titled “Ten Years of Hell for Three Children.” Still, no leads came in.

The case went cold.

Cozart, meanwhile, had stolen the identity of a man named David Stone and traveled to Arkansas where he obtained a driver’s license in Stone’s name. For over a dozen years, he posed as Stone, lived in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and worked at a Walmart, earning $1,400 per month, according to court records.

It took nearly two decades for the investigation to heat up again. In 2015, Tony Berosh, the district attorney of Beaver County, where Cozart had been prosecuted many years before, was approaching his retirement. It clawed at him that Cozart had never been found. “This was one of the really bad ones,” Berosh told the local newspaper. So Berosh met with Pennsylvania police in June 2015 and asked if there was anything they could do. He said to them, “I only have about six months left before I retire, and I wanted this guy.”

Pennsylvania police decided to send Cozart’s mug shot to a newly established FBI unit that maintains the largest database of faces in human history. The digital catalog of searchable “face photos” that the FBI has access to — some 548 million pictures — includes criminal mug shots, photos of terrorists taken by soldiers in Afghanistan and, more recently, state driver’s license and ID photos of ordinary citizens who have committed no crime at all, which are available to the FBI through relationships with each state.

Though Cozart had aged and changed his name, his face couldn’t lie. It matched the David Stone driver’s license photo. Investigators in Pennsylvania alerted the FBI Violent Crimes Task Force in Oklahoma that Cozart was believed to be in Muskogee. Officer Lincoln Anderson, a spokesman for the Muskogee police, told reporters that a group of police officers looked at Cozart’s photo and one had even recognized him.

“One of our officers said, 'Hey, I know that guy. He works at Walmart,' " Anderson said recently.

Police staked out the Walmart. Right before they arrested Cozart inside the store, at about 2:30 p.m., police asked him if he was indeed Lynn Cozart. “He said, ‘I used to go by that name,' ” Berosh, the district attorney, said.

Doug Sprouse, a program analyst at the FBI, touts the Cozart case as an example of how U.S. law enforcement is integrating facial recognition technology and other biometric identifiers into day-to-day policing to make the country safer.

“Within hours of getting this photo, that guy was in handcuffs,” Sprouse told International Business Times. “After 19 years, [Cozart] was brought to justice.”

Nearly a decade ago, fueled by fears of another 9/11-style attack, the FBI signed a $1 billion contract with military behemoth Lockheed Martin to develop and launch the unit, dubbed Next Generation Identification (NGI). The FBI began with a small pilot program in 2011. In late 2014, the facial recognition program finally became fully operational.

While facial recognition technologies and algorithms conjure images of a "Minority Report"-like control room, the reality is a bit more prosaic. Just as no two people have the same fingerprints, no two people have the same face. The technology essentially measures minute distances in a person’s face and logs the information. While these methods are still in their infancy, FBI officials say biometric technologies could help law enforcement locate and identify a suspect using surveillance videos, mug shots — or even photos taken from Facebook and Twitter.

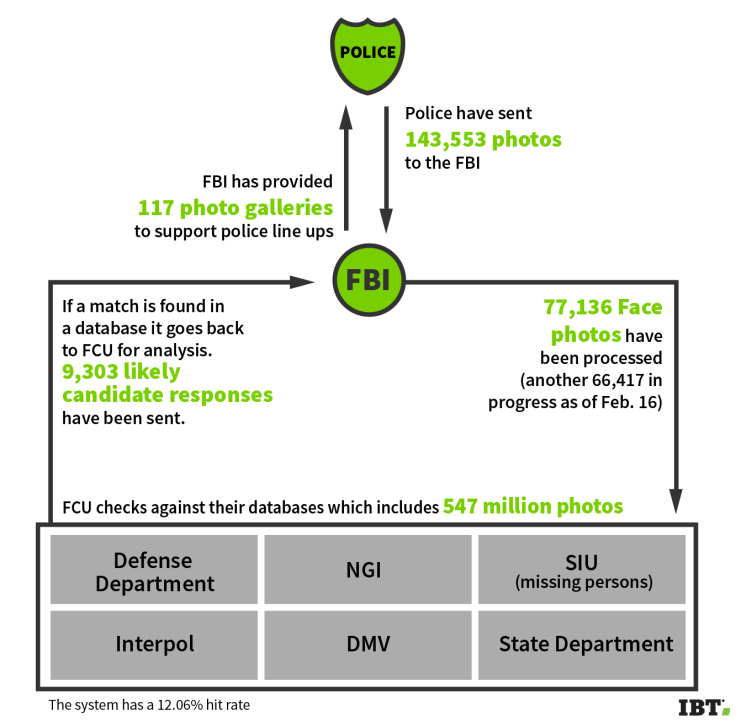

According to unreleased FBI data provided to IBT in February, the agency had, as of February, processed a total of 77,136 suspect photos and sent police 9,303 “likely candidates” since 2011. The FBI would not comment on how many of those cases led to an arrest.

In many ways, the FBI’s biometric program is an extension of the modern-day surveillance technologies that are making average citizens increasingly uncomfortable. Long gone are the days of clunky wiretaps and officers using telephoto lenses from disguised vans. Now local law enforcement agencies increasingly rely on sophisticated technology — largely sourced from the U.S. military — like Stingray devices, which intercept cell phone conversations, and police drones for aerial surveillance.

While federal officials and law enforcement hail the NGI program as a futuristic way to track terrorists and criminals, others have been notably less enthusiastic. Since the program's inception, national privacy groups have argued that biometric collection programs like NGI encroach on civil liberties. In the name of security and public safety, many advocates say the U.S. government is increasing its surveillance, through programs like NGI, on everyday citizens who have done nothing wrong.

“What we’re seeing is how counterterrorism and counterinsurgency tactics are being codified into everyday policing,” says Hamid Khan, a privacy advocate in Los Angeles and the founder of a grassroots group called Stop LAPD Spying. “In essence, we’re all suspects.”

The fear, of course, is that in this push for more security, Americans will inevitably lose their rights to privacy. This debate is raging now more than ever. On Feb. 16, just weeks after NGI opened its headquarters in a sprawling glass office tower in Clarksburg, West Virginia, Apple CEO Tim Cook publicly announced that his company would oppose an order giving the FBI “backdoor” access to the iPhone of one of the terrorists who killed 14 people in San Bernardino, California, in November.

While the FBI has argued (but has since retracted) that obtaining access to the shooter’s phone could provide valuable information on other suspects, Apple has protested the government's reach into its technology. “The government could extend this breach of privacy and demand that Apple build surveillance software to intercept your messages, access your health records or financial data, track your location or even access your phone’s microphone or camera without your knowledge,” Cook wrote.

Some, like Khan, believe the FBI is already doing that with its NGI biometric program.

FBI: ‘Say Cheese’

The FBI’s data collection operation has necessitated more real estate to house its growing workforce. Just after Christmas, the NGI opened the doors to its new facility, a 360,000-square-foot all-glass office building called the Biometric Technology Center. The center is situated on 1,000 acres of highly secured land in the low mountains of Clarksburg, West Virginia. It is housed in the Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) campus, which was opened in June 1995, and processes all national gun and background checks in the United States.

Security at the facility is tight. To enter, visitors must pass a federal background check. The campus even has its own police force — the third-largest in the state. When the FBI granted IBT a rare look inside the operation, Stephen Fischer, a 30-year FBI veteran, served as an escort. Fischer explains that the facilities are intentionally housed on a secured property set back nearly 1 mile from the nearest highway.

“Your average citizen has no idea what goes on here,” he says.

After all, the FBI wants privacy of its own — and for good reason. In the basement of an adjacent building, the bureau houses the world’s largest biometric database, a 100,000-square-foot data center — larger than a professional soccer field. It contains biometric records on some of the world’s most notorious terrorists and criminals, including fingerprints, iris scans and other bits of biographical data. The room itself requires 1,800 tons of cooling equipment, according to the facility's manager, Bob Scritchfield.

While there has been no physical attack on this particular FBI campus, the concerns over data breaches are very real. “People try to hack us all the time,” Scritchfield says. No attempts have been successful, he clarified.

At this West Virginia data center, in which rows upon rows of hard drives are stacked on individually marked tiles, several government agencies keep their biometric information on suspects. The Department of Defense, for instance, stores about 6 million photos of combatants taken in theaters of war. And if you’ve ever had a mug shot taken, your face exists on a hard drive in this room.

The FBI’s long-term vision for NGI is to have an “automated facial recognition capability,” according to official documents. In reality, what the agency is doing is expanding its long-established fingerprint system to include people’s faces. So just like a detective would dust for prints at the scene of a crime, the FBI wants to offer police the ability to scan someone’s face picked up on surveillance footage at a crime scene and search against the facial database.

To do this, the so-called “candidate” photos are culled by searching against state Department of Motor Vehicles photos in a program called Interstate Photo System. Depending on where you live, when you signed up to get your driver’s license, the fine print may have authorized officials to use your face to search against suspects in an active investigation. Sprouse, a management and program analyst at the FBI, is careful to clarify that the FBI, using these DMV photos, does not provide “one to one” matches but rather investigative leads for police.

The FBI launched this program with two participating states — Michigan and Arkansas — but 16 more have joined. By the end of 2016, Sprouse expects another half dozen states to sign up, adding millions more photos to the already massive repository.

The NGI program has not attracted nearly the amount of scrutiny or media attention as the FBI’s legal battle with Apple, but many surveillance watchdogs and privacy advocates have made monitoring the NGI their main focus. Both the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) have filed lawsuits against the NGI to obtain records about the program.

Jeramie Scott, who serves as general counsel for EPIC, has been perhaps the biggest thorn in the side of the NGI. In 2013, Scott filed a lawsuit to obtain internal documents about the NGI program. One of the disturbing factors Scott discovered after winning the suit and gaining the documents was that NGI’s facial recognition program operated with a 20 percent error rate. But what troubles Scott the most, he says, is how the FBI is using photos of innocent people who have never been convicted of a crime. The FBI maintains that it searches only against criminal databases — but the extension into DMV photos is a concerning development for Scott.

“I’m pretty sure when you went to get your driver's license, you weren’t thinking that this picture that was being taken was now going to be used for large-scale facial recognition searches,” he says.

The first DMV state agreement was signed with the FBI on May 14, 2012, by the Illinois Office of the Secretary of State. Since then, more than two dozen states have signed up. The NGI’s Interstate Photo System is a repository and thus does not have connectivity to perform facial recognition searches in the DMV repositories on its own. However, FBI staff will submit requests to DMVs with which the FBI has established agreements, and DMV staff perform the requested search and return results to the FBI. The results, between two and 50 photos, are sent as an “investigative lead.”

According to the FBI, in 2016 the NGI’s facial recognition unit was processing about seven photos per day in active investigations.

A Case of Mistaken Identity?

But what happens when the match turns out to be wrong? In fact, it's exactly that 20 percent error rate — the rate at which the system produces false positives — that has privacy advocates so worried. German Federal Data Protection Commissioner Peter Schaar, for instance, recently noted: "In the event of a genuine hunt, [false positives] render innocent people suspects for a time, create a need for justification on their part and make further checks by the authorities unavoidable.”

In other words, what happens if the computer makes a mistake, and someone innocent ends up in jail?

The FBI says this won't happen because the technology merely provides "investigative leads." "No one's going to go out and knock on a door and make an arrest based on the information we provide," Sprouse says. "There has to be supported information."

While that's true so far in the U.S., consider the case of Eddie David, a 39-year-old Australian man who was detained by federal authorities in 2015 when a facial recognition program alerted police that he was an illegal immigrant. David's attorneys said his arrest was purely a case of mistaken identity. "This is a very serious matter," his attorney told the Australian Broadcasting Corp.

There have been domestic mishaps as well. In the United States, John H. Gass, a 46-year-old Boston resident, sued the city in 2011 after he received a letter saying the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles (the state DMV) had revoked his license. Gass, who hadn't done anything wrong — he didn't even have any traffic tickets — says he was "shocked" when the letter came. According to his attorney, William Spallina, the state DMV was using an anti-terrorism facial recognition system. When the computerized system scanned Gass' face, the system returned three results: One for Gass' car registration, another for his motorcycle registration and a third for a separate man who, according to Spallina, "looked a lot like Gass" but wasn't him.

Because the algorithm was configured to trigger a fraud alert when it returned two identical faces with separate names, the state was "saying that was prima facie evidence of license fraud," according to his attorney. Subsequently, the DMV revoked his license, pending a hearing. As a result, Gass, who drove a truck for Boston's Department of Public Works, was out of work for two weeks. In January 2013, an appeals court dismissed Gass' hardship case on procedural grounds, but it stands out in Spallina's memory. "It was absurd," he says.

The Boston Globe, which first reported Gass' cases in 2011, noted that the facial recognition program has triggered over 1,000 investigations. While Boston doesn't track how many people are incorrectly identified, the Globe noted: "Some of those people are guilty of nothing more than looking like someone else."

While Scott, the privacy lawyer, hasn’t seen anyone sent to jail as a result of facial recognition gone awry, he says it’s a slippery slope either way. Right now, for example, it’s not illegal for a police officer or FBI agent to simply walk around in public places, scanning people’s faces in order to identify and potentially track them. (Think of it like Google Street View — but for law enforcement.) That, he says, could lead to a future in which surveillance cameras can instantly recognize and track people as they carry out daily activities. “There’s a lot of potential issues with facial recognition because of the ability to do it surreptitiously and in mass scale,” Scott says.

Jennifer Lynch, the staff attorney for the EFF and another vocal critic of the NGI program, argued before Congress recently that NGI will result in a massive expansion of government data collection, regardless of whether someone is guilty or innocent. “Biometrics programs present critical threats to civil liberties and privacy,” she said. “Face recognition technology is among the most alarming new developments, because Americans cannot easily take precautions against the covert, remote and mass capture of their images.”

Mobile Mug Shots?

In interviews at the FBI, the agency asserts that it does not — and has no plans to — implement any sort of real-time facial recognition program, but the methods for facial recognition are indeed expanding. In 2015, the FBI issued a request for proposals from companies that could provide new mobile technology that could take a person’s picture or fingerprint and instantly return an identity.

Explaining its request in official documents, the FBI says such technology would give its agents “an investigative advantage" and would "change law enforcement and undoubtedly save lives."

In fact, the San Diego Police Department is already using a pilot program to snap pictures of anyone who is arrested — using an iPad — sort of like instant fingerprinting but for the tech-savvy. This program raised alarm bells at the EFF, which wrote in September that “the biggest concern with the new mobile program is that it appears it will allow (and in fact, encourage) agents to collect face recognition images out in the field and use these images to populate NGI — something the FBI stated in congressional testimony it would not do.”

The FBI did not comment on how exactly the new mobile program will work — or whether those images will be used to populate the NGI database. (Fischer pointed to the 2015 CJIS Annual Report).

Regardless, the idea of officers snapping people’s pictures on the street chafes with some. At a recent meeting for Stop LAPD Spying, in which the NGI’s new program was discussed, Jamie Garcia, a 38-year-old oncology nurse, said she’s become fearful of any interaction with law enforcement, particularly because of these types of technology programs. “Under the rubric of anti-terrorism, all the past rules of civil rights and privacy and Constitution go out the window,” Garcia says. “We seem to be in a new era where anything goes. That scares me. That worries me.”

In the wake of the San Bernardino attack, however, there are renewed concerns over national security — and these concerns may help the FBI gain support for biometric collection programs. The FBI, however, has remained relatively quiet about how it plans to use mobile devices to collect facial scans of ordinary citizens.

‘Our Country’s Position Has Changed’

In charge of the NGI program, as well as this entire FBI campus, is Stephen Morris, assistant director of the CJIS, which has a staff of 2,500 full-time personnel. Morris, a former FBI agent, says he is driven purely in his desire to keep the country safe in whatever way he can, and using new high-tech tools like facial recognition is in the best interests of national security. Seated at a sprawling conference table in his West Virginia office, Morris says the NGI program “follows the rules of the law.”

“Everything we do here at CJIS, we do it with privacy in mind,” he says.

“I look at it like a 'glass half empty, glass half full' kind of conversation,” Morris says. “Folks who think if collecting biometrics is an invasion of folks’ privacy, I would contradict that and say it’s, no, it’s better confidence that we identify people with biometrics. The level of certainty that we have the right person goes up exponentially.”

While facial recognition programs have become fully operational, Morris also notes that other biometric identifiers — like iris scanning and even voice analysis — are on the horizon.

Morris added, “Our country’s position has changed ... We want to do everything we possibly can to protect our country and the citizens of our country, whether it’s terrorism or organized crime. But at the same time, we are not going to collect and store or house information and data that we are not either asked to collect or authorized to collect. Because balancing privacy and civil liberties — we cannot afford to compromise that.”

Morris then reiterated the Cozart case as an example of a recent success. The FBI was not able to provide any other specific cases in which it used facial recognition to locate a terrorist or other criminal.

For privacy advocates like Khan, the FBI’s NGI program is another example of the federal government spending hundreds of millions of dollars on a program that — intended to solve crime — ends up becoming an expensive and ultimately ineffectual surveillance program.

“With all these tools, there’s an information overload,” he says. “Our money is going towards these things — the surveillance industrial complex.” And the budget for such programs, Khan says, is “infinity — because there’s no end to the war on terror.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.