The Fed Is Expected To Begin Raising Interest Rates Soon, But How Quickly?

The U.S. economy added 211,000 jobs in November, all but cementing expectations that the Federal Reserve will opt to raise interest rates in December. Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s diagnosis of an economy that has “recovered substantially” since the recession was only bolstered by the data, which showed the U.S. unemployment rate is a healthy 5 percent.

Now, attention is turning to the expected pace of the Fed's rate rises in the coming year. With the first move likely to be a relatively mild 0.25 percent lift from the Fed’s current near-zero benchmark rates, markets have predicted the Fed’s pace will be more of a leisurely stroll than a steep hike. In the minutes of the rate-setting committee's most recent meeting, most participants saw interest rates rising on a "gradual path."

Whatever the pace, the Fed’s move has deep implications for the broader economy. Markets that have been begging for certainty will breathe a sigh of relief as ordinary borrowers see slowly rising interest rates on credit card debts and adjustable mortgages.

For the wider economy, however, the effects remain largely unknown.

Ripples And Waves

For Americans who don’t spend their days betting fortunes on tiny movements in currency exchange rates, it could take a while before the Fed’s expected liftoff makes itself felt.

“A quarter of a percentage point change in interest rates is almost imperceptible in terms of how it impacts the household budget,” said Greg McBride, senior vice president of Bankrate.com. “It’s the cumulative effect that you have to be mindful of.”

Consumers with credit cards and home equity lines of credit would be the first to feel the impact of multiple rate increases. Economists expect a more delayed impact on new mortgages that are usually pegged to U.S. Treasury bills, whose price already reflects expected interest rate hikes.

Over time, however, a series of slight rate hikes could build up to noticeable impact for borrowers. Within a year or two, McBride said, credit card users currently paying 15 percent could see their rate increase to 17 percent.

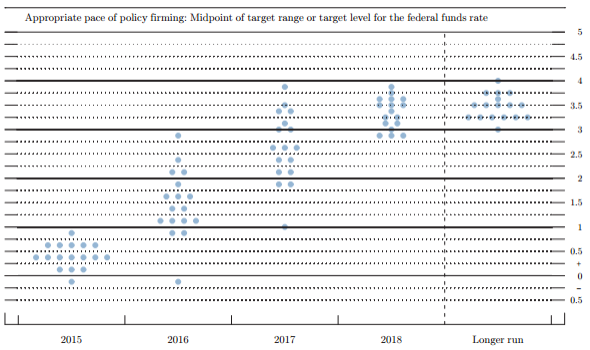

Members of the Fed’s rate-setting committee generally predict a gradual rise in interest rates. The so-called dot plots that reflect Fed officials’ interest rate expectations show benchmark interest rates rising to a median projection of roughly 1.25 percent by the end of 2016 and at least 2.5 percent by 2017.

Whether ordinary consumers feel them immediately, however, rate hikes still affect the broader economy. “Raising interest rates effectively raises the price of money, and that ripples out to every borrower and every financial instrument,” said McBride, who added that he expects the Fed’s action to be “a small ripple, not a big wave.”

Banks On The Rise

Consumers, of course, aren’t the only part of the economy that will feel the higher rates. Banks, which have been expecting the liftoff for months, will be happy to see interest rates rising for the first time in nearly a decade.

Higher benchmark interest rates mean greater profits for lenders, since there’s a wider margin between the lowest possible interest rate -- bound by Fed policy -- and the prices charged to borrowers. For the largest American banks, higher margins could mean a $10 billion windfall in 2016.

But just like with consumers, the pace of liftoff matters for banks. In a note to clients Friday, Goldman Sachs analysts pointed out that mega-lenders like JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE:JPM) and Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) should perform well with higher interest rates.

Those expectations rely on a slow pace of liftoff rather than a sudden hike. Global markets threw a fit when the Federal Reserve started to back off its stimulative asset-buying in 2013, an event known as the Taper Tantrum. Subsequently, the Fed took pains to choreograph its actions, and investors expect the same as the era of zero-interest-rate policy comes to an end.

'All About Wages'

While financial markets have been clamoring for a rate hike to ease uncertainty, not everyone is thrilled with the prospect of an immediate hike.

“It’s all about wages,” said Josh Bivens, research and policy director at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute. “We have a lot of room before we have an overheating economy that’s generating inflation,” Bivens said, arguing that the Fed should wait until wage increases ramp up before hiking rates.

The Fed is charged with maximizing employment and keeping inflation in check. Thirteen million jobs have returned since the depths of the recession. But with inflation largely nonexistent and wage gains yet to break out, Bivens said, the Fed shouldn’t rush to lift rates.

In the latest jobs report, wages picked up 2.3 percent overall and 2 percent for nonsupervisory workers. But wage gains of at least 3.5 percent are necessary to push up inflation, Bivens said, as companies counter the higher cost of compensation by increasing prices of goods and services.

Yellen has raised concerns over the relatively slow pace of wage growth during the recovery, though she has cited glimmers of faster growth in recent reports. “A sustained pickup would likely signal a diminution of labor market slack,” Yellen said in a speech in New York this week.

But Yellen has noted that measures like wage growth lag behind monetary policy changes, meaning the Fed could hike rates in December and wages wouldn’t feel the chill until much later. That’s where the pace of liftoff comes in.

“If it’s [a quarter of a percent] and it’s held for quite a long time, we could end up a year from now with about the same economy,” Bivens said of a December rate hike. That would match what the most dovish Fed officials have suggested. But a rise of 2 percent in 2016, which the most hawkish Fed members have called for, could spell trouble, Bivens added. “Two percent could pave the way for a noticeably slower economy.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.