Fed Warns Of Wage Pressures As Data Shows Inflation Still Rising

The Federal Reserve's preferred measure of inflation rose again in January and a new report from the central bank warned that price pressures could persist unless a shortage of available workers begins to ease.

The new inflation data, alongside the developing sense at the central bank that inflation may prove harder than anticipated to dislodge, will likely firm the central bank's intent to raise interest rates through the year, beginning with an initial hike in March from the current near zero level.

Policymakers will have to weigh one fresh and unanticipated set of risks in their discussion: The Russian military invasion of Ukraine could roil the economic outlook in unpredictable ways, and potentially undermine global growth and financial markets.

But Fed officials say that's unlikely to shift their immediate plans to begin tightening monetary policy in response to inflation that is not only high but continues moving higher.

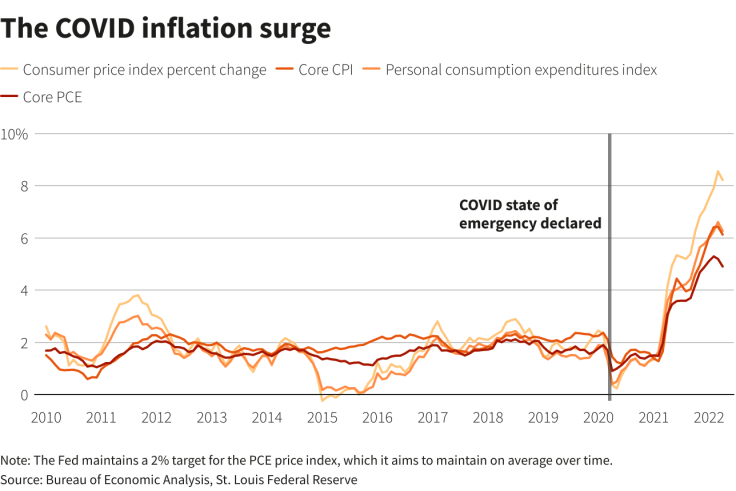

The personal consumption expenditures price index rose at a 6.1% annual rate through January, its highest since 1982 and more than triple the 2% inflation rate the Fed has set as its target for the U.S. economy.

That measure of annual inflation, reported monthly by the government, has been as higher or higher than in the prior month for 14 straight months - a run not seen since the 1970s and a blow to arguments commonly heard at the Fed last year

that rising prices would prove "transitory" and disappear as the economy reopened.

The month-to-month change in the same index, watched by some officials as a signal of moderation, showed no sign of easing.

Graphic: The COVID inflation surge The COVID inflation surge -

"EXCEEDINGLY HOT?"

The Fed is set to raise interest rates when it meets on March 15-16. Officials have been debating whether the initial "liftoff" should be a standard quarter point increase, or a larger half point hike to demonstrate the Fed's seriousness in controlling prices.

On Thursday, Fed Governor Christopher Waller flagged Friday's PCE inflation report as one to watch, saying if it shows "the economy is still running exceedingly hot, a strong case can be made for a 50-basis-point hike in March."

For now at least the data are not only hot but getting hotter: Since September the PCE index has jumped in steady increments from 4.4% to 6.1%, and has either risen or held level with the prior month in each report since November 2020.

In the Fed's latest monetary policy report to Congress, issued twice a year, central bank officials acknowledged that inflation had not eased as they expected, but in fact had broadened through the economy.

The "extraordinary circumstances" which the Fed had said last July were driving higher prices had given way to other dynamics, the report said, particularly a workforce falling far short of the numbers demanded by businesses to fill open positions.

"In the period ahead, the large price changes in goods may ease once supply chain disruptions finally resolve," the Fed report stated. "But, if labor shortages continue and wages rise faster than productivity in a broad-based way, inflation pressures may persist and continue to broaden."

Fed officials have largely downplayed the risk of a durable "wage price spiral."

But they've also been surprised by much of what's happened during the reopening from the pandemic.

The rapid spread of the Omicron coronavirus variant was expected to slow hiring and spending through the winter. It didn't happen. Job growth continued, and new spending data released on Friday showed consumer spending exceeded expectations.

Now the virus is fading and Fed officials anticipate a renewed sense of reopening in society and the economy will keep growth strong.

Trading in futures contracts based on expectations of Fed policy show investors downplaying the chance now of a half-point increase.

But the PCE report is still moving in the wrong direction for Fed officials hoping to avoid the most aggressive measures to control inflation.

"Though diminished, the chance of a 50bp move is still intact," wrote III Capital Chief Economist Karim Basta. Inflation at 6% "would definitely qualify as hot."

The main factor tempering arguments for a faster move by the Fed is the economic fallout from Russia's invasion of Ukraine. That could for a variety of reasons drive prices higher; it could also pose risks to global economic growth, or rattle financial markets in a way that could make the Fed less inclined to raise rates as fast as it would otherwise.

With the incursions less than 48 hours old that analysis was just beginning.

"In theory, the war has two contrasting effects on Fed policy: It could stoke inflation...and it could slow economic growth," wrote Piper Sandler macro analysts Roberto Perli and Benson Durham. "The Fed is likely to be more concerned about the latter than the former...The war will not delay liftoff...But it could well result in fewer rate hikes this year than the market is currently pricing."

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.