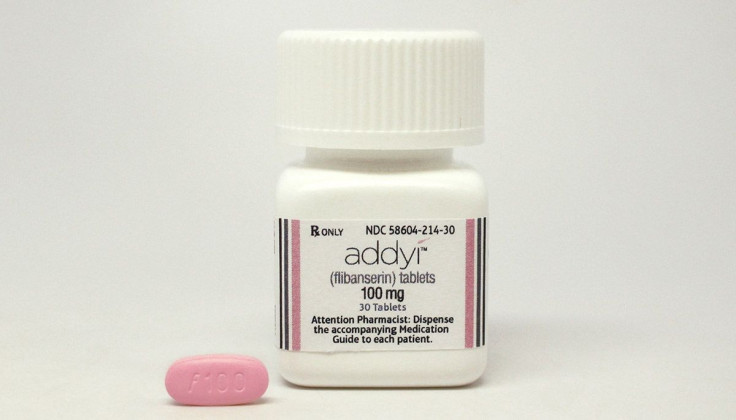

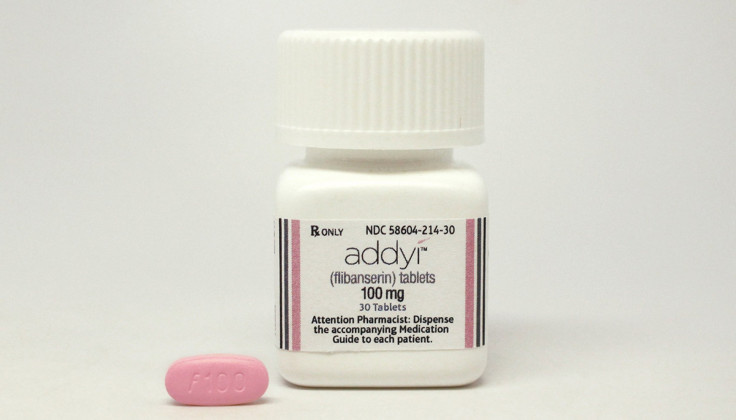

'Female Viagra' Approval: Did Sprout Pharmaceuticals Set A Dangerous Precedent In Earning FDA Go-Ahead For Addyi?

As Sprout Pharmaceuticals readies its one-of-a-kind drug for low sexual desire in women for an October market introduction, some medical experts are concerned that the company went too far in its push to gain federal approval for the drug, known as Addyi.

When the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Addyi last week, Sprout said the treatment would help millions of American women. Supporters are lauding the move as a milestone for women’s health akin to the arrival of the first birth control pill more than five decades ago. Sprout’s detractors, however, say the company set a dangerous precedent, blurring the line between traditional sponsorship of a new drug and advocacy on its behalf.

Critics point out that the company donated money to cover plane tickets and lodging for patients who spoke out in favor of Addyi at FDA meetings and participated in the rollout of a major public campaign urging the approval of drugs that address women’s sexual health issues.

“Sprout figured out a way to game the system by providing prepared patients and making those patients available to the FDA and the press,” says Leonore Tiefer, a therapist at New York University who led an opposition campaign called New View. “It was sort of one step beyond celebrity spokespeople.”

Tiefer and others warn that Sprout used political strategies, including sponsorship of a group called Even the Score, to pressure the FDA to approve a drug it rejected in 2010 and 2013. Sprout Pharmaceuticals was purchased by Valeant Pharmaceuticals on Thursday in a $1 billion deal, and its success in earning approval and attracting a large corporate buyer for the company may inspire other startups to use similar tactics.

Sprout is one of 26 sponsors of Even the Score, which leads a campaign for equality in sexual health, according to the website. The group's core tenet is that women should have medical treatments for common sexual health issues, just as men have access to erectile dysfunction drugs. Even the Score played an outsized role in launching online petitions, lobbying Congress and recruiting patients to attend FDA meetings about both female sexual dysfunction and the approval of Addyi, which treats a form of low sexual desire known as hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD).

“I totally agree with the mission that women deserve equal consideration when it comes to sexual health,” Cindy Whitehead, CEO of Sprout Pharmaceuticals, says.

But others see the group's motives quite differently. “It's a huge pressure campaign funded not entirely but significantly by the company,” Dr. Sidney Wolfe, senior adviser at Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, says.

Lately, the FDA has invited more patients into the drug development process at an earlier stage than ever before – a move that has garnered broad support among physicians and patients' groups. Only patients can offer insight into what it’s like to live with a condition. But their growing role may also present new opportunities for drug companies to shape the conversation by sponsoring patients with a specific experience that happens to closely align with the company’s own commercial goals.

Members of the public have always been welcome to testify at FDA advisory committee hearings and the agency even hires patients to serve on these committees and cast an official vote on each new drug. But with the 2012 renewal of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act, the FDA pledged to organize 20 public workshops focused on specific disease areas to permit more patients to weigh in on the need for new treatments. So far, the agency has hosted 14 of these meetings on subjects from narcolepsy to Chagas disease.

Last October, the FDA organized a workshop on female sexual dysfunction. Of the 50 patients who attended the meeting in person, 13 voluntarily disclosed that their travel expenses had been paid by a meeting organizer called Veritas that received grants from Sprout, Even the Score and the Institute of Sexual Medicine to arrange for their travel to the event.

“It's a good idea,” Wolfe says. “But it's a matter of how it's done and the record thus far sees it being very much tilted toward the desire of the companies and their willingness to organize people to speak out.”

Though the FDA organizers asked participants to voluntarily disclose conflicts of interest, it’s impossible to know how many actually did. Several dozen women and men, wrapped in green scarves distributed by Even the Score, posed in front of the FDA headquarters for a photo posted to the group’s Facebook page the day after the event.

Tiefer says the FDA should limit the number of people whom drug companies and advocacy groups can bring to these meetings. She and Wolfe also suggest the FDA should find a way to recruit patients with varying experiences whomay not otherwise be represented because there is no clear corporate sponsor with an interest in them.

"I think these patients were selected by Even the Score because they were telegenic, articulate and because they had a positive story to tell," Tiefer says. "They adhere to the line that conforms most closely to the company’s sales line for diagnosis and treatment.”

Sally Greenberg, executive director of the National Consumers League who advocated on behalf of Addyi, points out that opponents such as Tiefer also recruited patients who attended the FDA meeting. And she says those patients who showed up in buses provided by Even the Score still provided valuable insight. “They're real people,” she says. “It's not manufactured testimony.”

Sprout has also been accused of applying political pressure to further its commercial goals. Following the FDA’s rejections, Sprout appealed the agency’s decision. That appeal was denied in February 2014, and Sprout was instructed to complete further safety tests. While the company was conducting those tests and preparing its application for re-submission, Even the Score hosted a Senate briefing in September of 2014 on HSDD and the lack of treatments available to women who suffer from it.

“Even the Score is not PR; it’s patient advocacy,” says Whitehead. “I am a big believer that women should advocate for themselves around their health. Nobody knows more than you what’s going on -- if something isn’t normal for you, if something has changed.”

Whitehead and her husband Bob, who co-founded Sprout, contributed at least $39,250 to Democratic PACs between June and September of 2014, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. They re-submitted the application for Addyi with the results of new safety tests in February 2015. In March, 11 Congressional Democrats wrote a letter to FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg to urge the agency to pursue treatments for female sexual dysfunction, and highlighted Sprout's resubmittal.

The mere suspicion of creeping influence may also cast pharmaceutical companies in a negative light, even when there is no basis for it. Dr. Lisa Larkin, an ob-gyn at University of Cincinnati, recently joined Even the Score as scientific co-chair. She was immediately criticized on Twitter for accepting money from drug companies, even though she says she receives no compensation for her role in the organization.

“I believe in Even the Score as an extension of what I do in the office. I do patient advocacy. I'm the champion for my patients. I'm looking out for them," she says. My sense is that everyone is trying to play by the books and do the right thing.”

In June, Sprout pledged to not engage in any consumer advertising for Addyi for 18 months following the drug’s approval. But soon after the FDA announced its decision, Even the Score published a video on its website thanking the FDA. The lead actor in that video opened with, “Hey, did you guys hear? The FDA just approved the first-ever medication for women’s sexual desire.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.