First Known Rubella Virus Relatives Found In Uganda, Germany

KEY POINTS

- Scientists discovered two viruses related to the rubella virus in animals

- The findings suggest that rubella virus possibly originated in animals

- Researchers are now trying to determine whether the rubella vaccine could be effective in all three viruses

Two research teams have found the first known relatives of the rubella virus. The findings provide clues regarding the origin of the virus, which has remained a mystery for years.

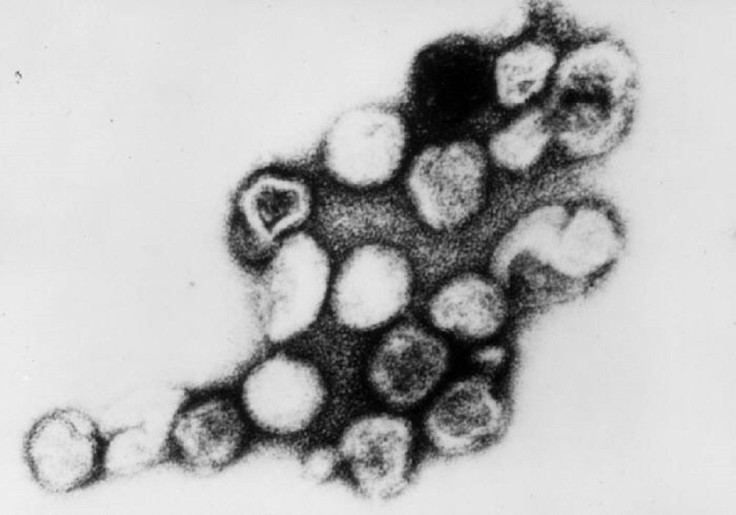

Rubella, also known as German measles, is a contagious disease caused by an airborne virus that has been known to be the only member of its virus family. It had not been found in animals. Although rubella disease was first described in 1814 and the rubella virus was first isolated in 1962, the actual origin of the virus and the disease remained a mystery.

Most people who get infected by the virus experience mild symptoms such as a low-grade fever, sore throat and a rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body.

Although the symptoms are generally mild, the virus can be particularly worrisome for pregnant women because it can cause a miscarriage or lead babies to have birth defects such as heart problems, spleen damage or loss of eyesight, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says.

Rubella has largely been eradicated, thanks to the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. However, a new study published in the journal Nature describes two rubella relatives found in two different places: Germany and Uganda.

"Here we describe ruhugu virus and rustrela virus in Africa and Europe, respectively, which are, to our knowledge, the first known relatives of rubella virus," the researchers wrote in their study, for which the two teams collaborated.

The two teams were working on separate projects and neither was looking for rubella when they discovered the virus' relatives. The team in Uganda was actually looking for coronaviruses in bats prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, while the team in Germany was trying to find out what killed several animals at a German zoo.

The team in Uganda found the virus, named ruhugu virus, in the oral swabs collected from leaf-nosed bats. The team in Germany found the other rubella relative, now called rustrela virus, in acutely encephalitic animals in a zoo and also in wild yellow-necked field mice.

Between the two viruses, ruhugu appears to be the closer relative, with just one amino acid difference from rubella, while rustrela has several amino acid differences.

The teams found the new viruses in nearly half of the bats and mice they tested, suggesting that animals can be carriers of the virus without getting sick and that the rubella virus we know possibly originated in animals.

"There is no evidence that ruhugu virus or rustrela virus can infect people, yet if they could, it might be so consequential that we should consider the possibility," said Tony L. Goldberg, study co-author and professor of epidemiology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison) School of Veterinary Medicine, in a news release. "We know that in Germany, rustrela virus jumped among species that are not at all closely related. If either of these viruses turns out to be zoonotic, or if rubella virus can go back into animals, that would be a game changer for rubella eradication."

Now, the researchers are also trying to determine whether the rubella vaccine could be effective in all three viruses.

The study also stressed the need for conservation efforts. When humans and animals are closer together, due to various reasons including human encroachment of animal habitats, the risks for diseases to jump from animals to humans and vice versa could increase.

"Our findings raise concerns about future zoonotic transmission of rubella-like viruses," the researchers wrote. "Viruses stay in their place when ecosystems are intact," Goldberg said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.