First US Offshore Wind Energy Projects Could Deliver Jolt Of Momentum To Struggling Sector

By the time summer rolls around, five wind turbines, each rising 600 feet, could be spinning in the Atlantic Ocean near Rhode Island. Two more could spring up off the coast of Virginia by late next year. America’s first offshore wind farms will arrive after more than a decade of fits and starts, and they could deliver a jolt of much-needed momentum to the struggling industry.

Yet building the next, bigger offshore wind projects will require states stepping in to help defray the sky-high electricity costs and attract wary investors, analysts say. A handful of other East Coast wind farms are in the works, but none are likely to come online this decade without stronger clean energy policies, or better financial incentives.

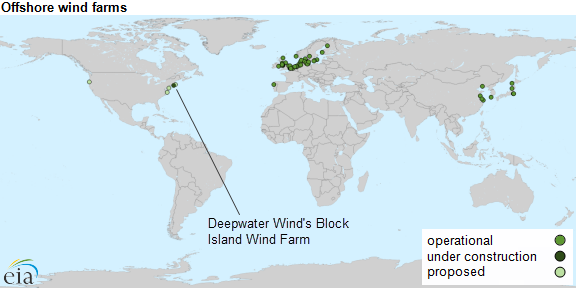

Meanwhile, as the U.S. completes its two tiny projects, thousands of wind turbines are already producing clean electricity off the shores of Europe, China and Japan.

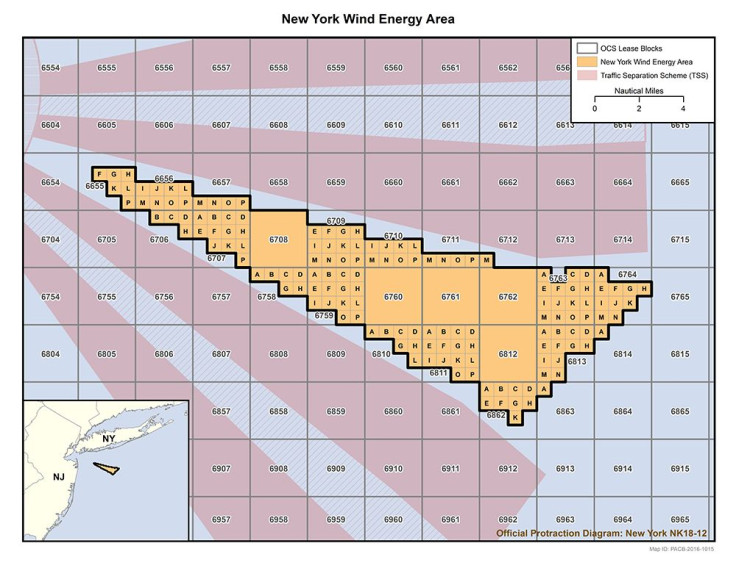

The next potential hot spot for America’s offshore wind experiment could be near New York City. The Obama administration last week said it identified an 81,100-acre “wind energy area” off the coast of Long Island where developers could propose a large-scale wind farm. The U.S. Interior Department had worked since 2011 to establish the zone, which is tucked between shipping channels and commercial fishing areas.

“Today’s milestone marks another important step in the president’s strategy to tap clean, renewable energy from the nation’s vast wind and solar resources,” Interior Secretary Sally Jewell said March 16 in a statement.

A hulking offshore wind farm near the nation’s most populated region could solve a major problem plaguing onshore wind and solar projects: the lack of space.

New York State has about 1,750 megawatts of land-based wind power, but the majority of projects are upstate, hundreds of miles from the crowded cities to the south, meaning expensive transmission lines must connect supplies to demand centers. The same space constraints helped drive European countries to build 84 offshore wind projects, which total more than 11,000 megawatts in capacity.

Still, building wind projects closer to New York City won’t help curb offshore wind power’s large price tag. Electricity from those projects costs roughly four times more than traditional wholesale power, which is especially cheap right now due to low natural gas prices, said Amy Grace, head of wind analysis at Bloomberg New Energy Finance in New York. Onshore wind and solar power are also getting relatively cheaper as technologies improve and projects reach mass scale.

For developers, “convincing a utility to pay four times the price for your offshore power is not an easy task,” Grace said.

A handful of New York utilities in recent years had considered proposals for offshore wind farms near Long Island and New York City. But they ultimately canned those plans because of the higher electricity costs, and no new developments are in the works.

New York regulators could change this dynamic by updating the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard. Gov. Andrew Cuomo is pushing to require utilities to get 50 percent of their power from renewable energy sources by 2030, a measure the Public Service Commission could finalize this summer. If the policy excludes nuclear and hydroelectric facilities, it would effectively compel utilities to invest in offshore wind — and require state subsidies to pay for the cleaner electricity, Grace said.

“If they have to hit these targets, then maybe this starts to make sense as to why you spend that much money,” she added.

For developers of offshore wind projects, buy-in from utilities is the most critical component, and the hardest to get.

The Cape Wind project planned near Cape Cod, Massachusetts lost its two long-term utility contracts last year after the developer missed deadlines for completing financing and starting construction. The $2.5 billion project, which would install 130 large turbines in Nantucket Sound, has struggled for 15 years with a host of financial, regulatory and legal challenges. Without the power contracts, the project’s fate is uncertain.

Another developer, NRG Bluewater Wind, withdrew from its 200-megawatt contract with Delaware utility Delmarva Power after failing to find investors, who worried the risk was too great in the absence of long-term federal tax credits and loan guarantees.

But Deepwater Wind, the developer behind the five turbine project in Rhode Island, did secure a long-term power contract with the utility National Grid, largely because the 30-megawatt project is relatively small, and thus less risky and costly than larger proposals. The Providence company also secured debt and equity funding from a handful of backers, including KeyBank National Association and the French bank Société Générale.

The $290 million wind farm near Block Island will supply nearly all the electricity for the island’s 1,000 year-round residents. The community already pays some of the nation’s highest electricity prices due to its isolation and large dependence on diesel-fueled generators during the summer tourist season.

The project’s backers said they hope the wind farm will breathe new life into the sector after years of dashed hopes and delayed progress. “The first obstacle is skepticism. People thought that it would never happen,” said Jerome Pecresse, president and CEO of GE Renewable Energy.

General Electric launched the division in November after acquiring France-based Alstom SA’s power business and is now supplying the five turbines to the Rhode Island wind farm. GE is also working with Dominion Virginia Power to supply two offshore turbines for a 12-megawatt demonstration project near Virginia Beach.

Speaking by phone from China, Pecresse said the Rhode Island project is a significant step in proving the U.S. offshore wind market is a reality. “The next step will be to scale what we do at Block Island,” he added. “I believe it [the offshore market] will move faster in the U.S. than expected.”

Grace, the BNEF analyst, said she is more skeptical that Block Island will provide the spark that ignites other offshore wind projects. Even as developers eye New York and Virginia, she said the next offshore wind farm is unlikely to come online until after 2020 absent stronger policies or subsidies.

“The question is, is Block Island the first of a series of projects that we see coming? The short answer is, probably no … if everything stays status quo,” she said. “A number of states are looking at subsidizing offshore wind in some way to make that less of a hurdle for utilities, but there’s nothing concrete.”

She said the next project after the smaller wind farms in Rhode Island and Virginia could be a commercial-scale project near Maryland. Former Gov. Martin O’Malley in 2013 signed the Maryland Offshore Wind Energy Act, which appointed state regulators to create credits to subsidize a large wind project 10 miles off Maryland’s coast.

US Wind Inc., an Italian-backed company, recently won federal leases to develop a 68-turbine, 500-megawatt project near the state. The developer, which has set up offices in Baltimore, said it expects to complete construction and operations blueprints for the $2.3 billion project by 2017, the Baltimore Sun previously reported.

Other promising developments are underway for America’s West Coast, although Pacific Ocean projects are in an even earlier stage than their Atlantic counterparts. Unlike the East Coast, which has a wide continental shelf, the seabed in the Pacific is far too deep to install turbines.

But Statoil, the Norwegian energy giant, is planning to build a 30-megawatt wind farm on floating structures near Peterhead, Scotland. Production is slated to start in late 2017. If successful, the floating wind farm could provide a blueprint for developers in California, Oregon and Washington.

The U.S. could still take decades to catch up with Europe’s offshore wind market, which counts more than 3,200 individual wind turbines near 11 countries, the European Wind Energy Association reported. China has hundreds of offshore wind turbines, with plans to grow the sector 30-fold by 2020.

Even so, GE’s Pecresse said he is optimistic that as the U.S. slowly enters the market, costs will drop and investors will shake their nerves. “For offshore wind, the challenge is to get to economies of scale that will generate savings,” he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.