FOMC Meeting Preview: Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke's Press Conference To Provide Clues On When QE Will End

Recent improvement in labor market conditions and growing concerns over the costs of ultra-loose monetary policy probably won’t prompt the U.S. Federal Reserve to cut back on its monthly asset purchases anytime soon. [Update: We are live blogging the event here.]

The Federal Open Market Committee, which sets most of the Fed’s monetary policy, meets for two days starting Tuesday. Instead of a long gap between the FOMC statement and Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s press conference, the statement -- along with the updated survey of economic projections from FOMC participants -- will come out at the revised time of 2 p.m. EDT Wednesday, followed by Bernanke’s press conference at 2:30.

The statement may be revised modestly to reflect two offsetting changes since the last FOMC meeting.

The better U.S. data of late should convince the Fed that the economy has resumed growing after the temporary pause noted in January.

Conversely, several of the downside risks feared by Fed officials have intensified: The sequester was not averted, news from Europe has been disconcerting (Italian elections and Cyprus bailout), and Chinese data have softened.

The net effect is likely to be no change in either the quantitative easing purchase pace or the forward guidance, according to Michael Hanson, senior U.S. economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

The January minutes indicated that the committee and Fed staff will be reviewing the asset purchase plans at this meeting. Investors likely won’t see much of this debate until the minutes are released in three weeks’ time. Some economists expect a revised exit strategy statement, which is possible but more likely later this year, Hanson said.

Hence, the main focus will be on what Bernanke says in his press conference. Bank of America Merrill Lynch Chief U.S. Economist Ethan Harris looks for him to insist that the benefits of QE outweigh the costs, and that the Fed has the tools to exit when the time comes.

In response to the financial crisis and deep recession of 2007-2009, the Fed not only slashed official interest rates to rock-bottom levels but also bought more than $2.5 trillion in mortgage and Treasury debt in an effort to push down long-term interest rates and spur hiring.

The Fed is currently buying $85 billion in bonds each month and has said it plans to keep purchasing assets until it sees a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market.

The central bank has also promised to keep interest rates low until unemployment falls to 6.5 percent or inflation rises to 2.5 percent. Both thresholds seem far off.

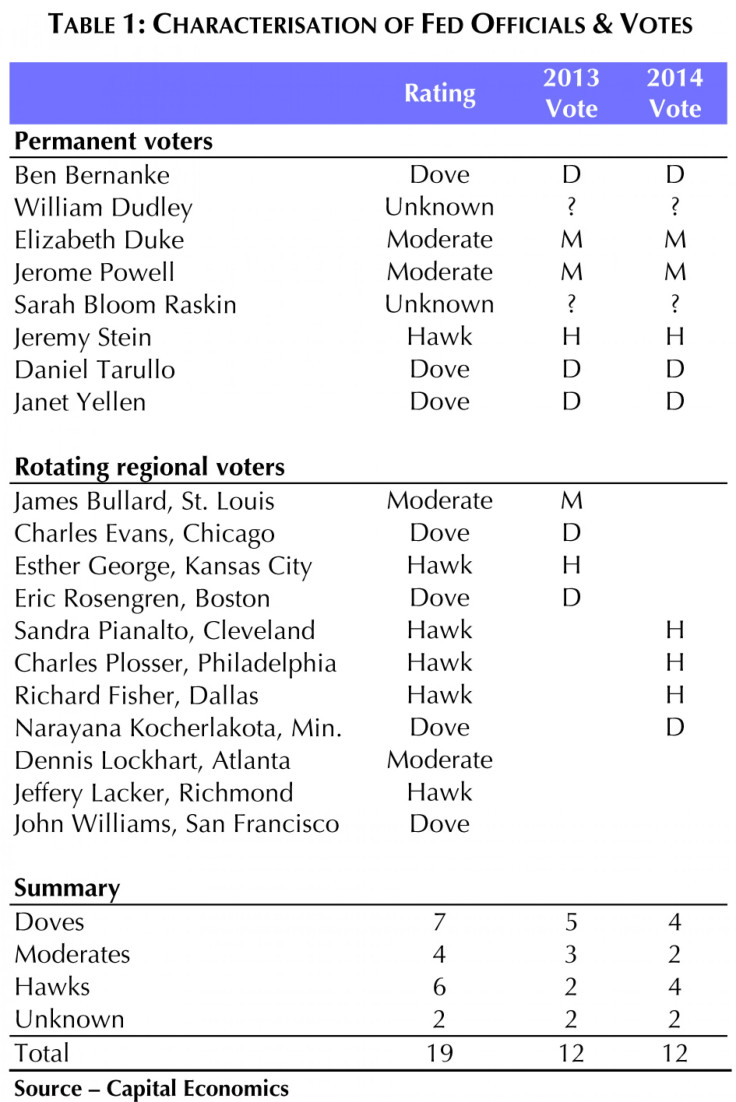

The acceleration in job growth in February and the fall in the unemployment rate to a four-year low of 7.7 percent probably doesn’t constitute the substantial improvement in labor market conditions that the Fed is looking for. Admittedly, the three-month average change in private payrolls has been above 200,000 for three consecutive months. But Chicago Fed President Charles Evans said this would need to be maintained for three more months to count as a major pickup, according to Paul Dales, senior U.S. economist for Capital Economics. The Fed will also be concerned by the hit to activity and employment over the coming months from the sequester federal spending cuts that began at the start of March.

While most market participants are not expecting any significant developments from this week’s FOMC meeting, Societe Generale Senior U.S. Economist Aneta Markowska see an outside risk that the Fed could alter its guidance on asset purchases and link it to an unemployment threshold.

“We see a significant risk that the Fed will switch from qualitative to quantitative guidance on asset purchases,” Markowska said in a note to clients.

So far, the Fed has tied any liftoff in rates to a 6.5 percent unemployment rate but has left the guidance on the balance sheet deliberately vague, primarily because the costs and benefits of QE were not understood as well.

Minutes of the Fed's Jan. 29-30 policy meeting showed “many participants” felt the potential risks posed by the bond purchases could warrant tapering off or ending them before hiring picks up. However, several others argued there was a danger in halting them prematurely.

Bernanke appeared to be in the latter camp. "To this point, we do not see the potential costs of the increased risk-taking in some financial markets as outweighing the benefits of promoting a stronger economic recovery and more rapid job creation,” he said in his recent semi-annual monetary policy testimony to Congress.

"There is no risk-free approach to this situation," Bernanke said. "The risk of not doing anything is severe as well. So, we are trying to balance these things as best we can."

The Fed has been studying this issue extensively since the December meeting and Markowska believes it is getting closer to another shift in communications.

“Looking at the latest consensus figures, we believe that the markets are currently priced for termination of asset purchases around 7.25 percent to 7.5 percent unemployment,” Markowska said.

In other words, the Fed might end QE sometime between late 2013 and mid-2014.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.