France's New-generation Nuclear Plant Delayed Again

Electricity giant EDF on Wednesday announced a further delay and cost overruns for France's flagship new-generation nuclear plant, in a blow to President Emmanuel Macron's strategy of making atomic power a cornerstone of energy policy.

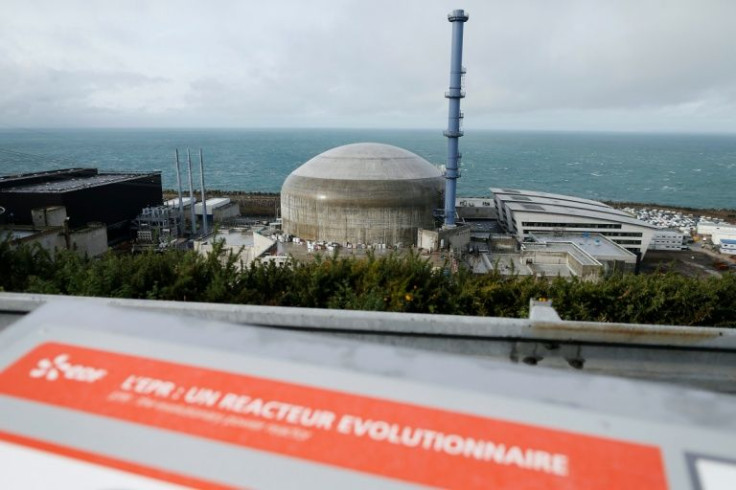

EDF said that the Flamanville plant on the Channel coast would not be loaded with fuel until the "second quarter of 2023", instead of late 2022.

The statement came after Macron announced plans for new reactors to provide low-carbon energy and as France backs classing nuclear as a "green" technology under future EU rules.

Projected costs had increased by another 300 million euros ($340 million) to 12.7 billion euros, EDF said -- around four times more than the initial forecast of 3.3 billion euros.

Construction on the new-generation EPR plant began in 2007, and was supposed to be finished in 2012.

In November, Macron had announced that "for the first time in decades, we will restart construction of nuclear reactors in our country" -- as well as "developing renewable energy".

The plans would "guarantee France's energy independence" and help reach its goal of being carbon neutral by 2050, he added.

But the president, who has yet to officially confirm that he plans to stand for re-election in April, was short on details like where or when the new plants would be built.

The Flamanville overruns were "a fiasco at the French public's expense", said Greens presidential candidate Yannick Jadot.

Left-wing candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon called the news a "shipwreck for the nuclear sector" -- long one of the crown jewels of French industry.

With 56 reactors providing over 70 percent of France's electricity, according to EDF, Paris has led the charge for nuclear power to be recognised by the European Union as a green technology eligible for carbon-neutral investment.

Allying with eastern EU member states like Poland and the Czech Republic, the push to include atomic energy in the so-called green "taxonomy" has set it at odds with traditional partner Germany.

Berlin is in the process of shutting all its nuclear plants by the end of this year and Germany's governing coalition now includes the Green party, rooted in part in opposition to the technology going back to the 1970s.

Environment Minister Steffi Lemke has said it would be "absolutely wrong" to include nuclear energy on the list, as it "can lead to devastating environmental catastrophes".

"We agree to disagree on the issue" with the French, German Europe Minister Anna Luehrmann told AFP last week.

Germany's no-nuclear policy has not been without its disadvantages, with critics saying it has delayed the country's exit from coal power and made it more dependent on natural gas from Russia.

State-controlled EDF said Wednesday that the latest delay at Flamanville was partly due to "an industrial context that has been made more difficult by the pandemic".

The plant has experienced multiple technical setbacks, with the national nuclear watchdog identifying problems with welding in 2019 which had to be redone.

Although Flamanville is the only reactor under construction in France, three others are in operation around the world: two in China and one in Finland.

EDF was also picked to build a two-reactor plant at Hinkley Point in southwest England in 2016, but this project too has been hit by delays and cost overruns.

Many of France's existing nuclear plants are coming to the end of their expected lifespans of 40 years.

If the reactor is loaded with fuel in Flamanville in the middle of next year, it would be expected to begin commercial operations around five or six months later.

The government has said a coal plant at Cordemais in western France will be allowed to operate until 2024 until the Flamanville site is brought online.

© Copyright AFP 2024. All rights reserved.