Fukushima Radiation Now A Global Disaster: Japan Finally Asks World For Help, Two Years Too Late

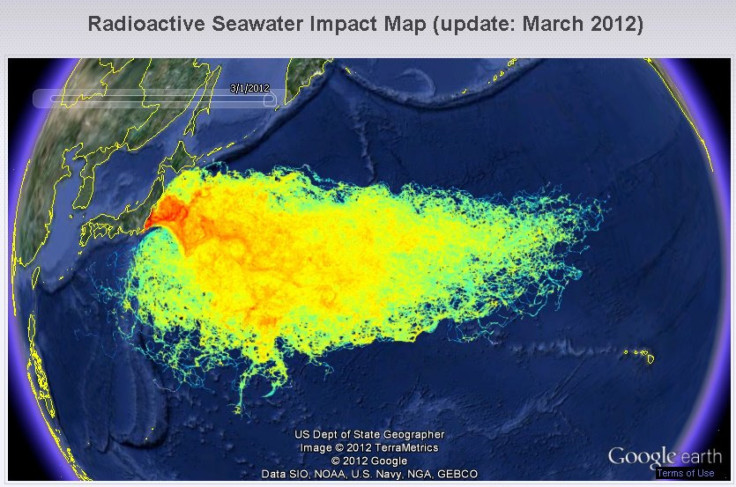

The March 2011 crisis at the Fukushima nuclear power plant was the world's worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986, but it took two and a half years after the fact for the Japanese government to ask the world for help.

On Sunday, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said Japan is finally open to receiving global aid to contain the ever-growing disaster at Fukushima, where radioactive water leaks continue to contaminate the Pacific Ocean’s ecosystem, and thus, the entire world’s food supply.

"We are wide open to receive the most advanced knowledge from overseas to contain the problem," Abe said, in English, to open a conference on energy and the environment at an international science forum in Kyoto. “My country needs your knowledge and expertise.”

Abe has many times attempted to assuage national and international concerns. After Tokyo was named host in early September for the Summer Olympic Games in 2020, Abe repeatedly told the International Olympic Committee that the Fukushima situation “is under control.”

“It has never done and will never do any damage to Tokyo,” Abe said. “It poses no problem whatsoever. … There are no health-related problems until now, nor will there be in the future. I make the statement to you in the most emphatic and unequivocal way.”

During Sunday’s speech, however, Abe offered no assurances that Fukushima is “under control.”

A Flood Of Leaks

Even prior to Monday’s power failure at Fukushima, the Tokyo Electric Power Co., the operator of the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant, just last week said more than 110 gallons of contaminated water spilled when workers overfilled a storage tank without a proper gauge. Tepco has admitted that "most" of the 110 gallons from the tank have reached the sea, but that tank is just one of about 1,000 tanks placed within Fukushima specifically to hold water used to cool the melted nuclear fuel in the plant’s broken reactors each day. And these leaks, which are extremely hazardous, are unfortunately not rare.

The contamination leaks aren’t a result of technical problems with the water tanks, but rather human error. In fact, there have been at least three major leaks in the last 30 days, with several metric tons of contaminated water seeping into the ground and running off into the ocean, and all of the accidents were results of sloppy mistakes, rather than mechanical failures.

“It is extremely regrettable that contaminated water leaked because of human error,” said Katsuhiko Ikeda, the administrative head of the Nuclear Regulation Authority. “We must say on-site management is extremely poor.”

Engineers and industrial experts have blamed Tepco for its carelessness in handling the contaminated water, pointing to protective barriers that are too low, insufficient inspection records of the tanks, a lack of water gauges, and the company’s decision to lay connecting hoses directly on the grassy ground. Regulators have even criticized Tepco for lacking the basic skills to properly measure radioactivity.

"As far as Tepco people on our contaminated water and sea monitoring panels are concerned, they seem to lack even the most basic knowledge about radiation," said Kayoko Nakamura, a radiologist and commissioner of the Nuclear Regulation Authority. "I really think they should acquire adequate expertise and commitment needed for the job.”

In August, Tepco admitted that a cumulative 20 trillion to 40 trillion becquerels of radioactive tritium had “probably” leaked into the Pacific Ocean since the disaster; the legal limit of radiation in water is 30 becquerels per liter.

Calling The World

The Japanese government took charge of the Fukushima situation only in August, when Abe finally ordered an intervention.

“It is an urgent problem,” he said. “We will not leave this to Tepco, but put together a government strategy. We will direct Tepco to make sure there is a swift and multi-faceted approach in place.”

This “multi-faceted approach” may mean asking the world for help, but Japan is continuing to let Tepco remain in charge at Fukushima, and has not committed to any further training or regulation at the plant.

“There must be a systematic problem in the way things are run [at the Fukushima Dai-ichi],” Tetsuro Tsutsui, an engineer and a member of a citizens group proposing safety measures for Fukushima, told Al Jazeera.

According to Russia's ITAR-TASS news agency (via RT), the safe level of radiation is 1-13 millisieverts per year; at Fukushima, however, the level of radiation is estimated at 100 millisieverts per hour.

Japan has offered but a few solutions for the persistent radiation leaks, including protective barriers to prevent the flow of contaminated water into the ocean, which have been criticized for being much too low. Earlier this month, the Japanese government approved a plan to bury refrigeration pipes 100 feet below sea level for about a mile around the radioactive site to essentially freeze the ground to prevent water flow; the job is expected to take 18 months and cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Japan recently began accepting project proposals from citizen groups and private companies eager to address the contaminated water issue, but the Japanese government only recently posted a notice in English, as the prior notice, in Japanese, had clearly excluded any kind of foreign participation.

Japan recently agreed to accept the help from France, which will help decommission and dismantle the crippled nuclear reactors at Fukushima. Russia, which originally offered to help Japan contain the Fukushima nuclear disaster (and again recently renewed its offer), is still waiting to be taken up on its offer. But while Chernobyl and Fukushima were the only two nuclear disasters to measure Level 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale, Chernobyl only contained 180 tons of nuclear material prior to the catastrophe; comparatively, Fukushima contained 1,760 tons of nuclear material.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.