Future Of Artificial Intelligence: Robots Will Steal Jobs, Not Take Over The World, White House Says

The White House National Science and Technology Council released a report on the future of artificial intelligence Wednesday that predicted regulatory challenges, future job losses, more capable U.S. cyber-defenses and little chance of a Terminator-esque super-intelligent computer apocalypse.

“If computers could exert control over many critical systems, the result could be havoc, with humans no longer in control of their destiny at its best and extinct at its worst,” the report, titled “Preparing for the Future of Artificial Intelligence” said. “This scenario has long been the subject of science fiction series, and recent pronouncements from some influential industry leaders have highlighted these fears.”

The report was likely referencing comments from Microsoft founder Bill Gates, theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and Tesla CEO Elon Musk—and, for what it’s worth, several Arnold Schwarzenegger-led dystopian films—warning of the dangers of AI.

Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates Warn About Artificial Intelligence https://t.co/M0sl8H9lVG

— Matthieu Mosettig (@Mattborass) October 5, 2016

But the NSTC, a Cabinet-level group that coordinates science and tech policy, held “a more positive view” of AI’s future, with the technology’s systems serving as “helpers, assistants, trainers and teammates of humans.” The White House report came out ahead of its Frontiers Conference Thursday in Pittsburgh, Pennslyvania.

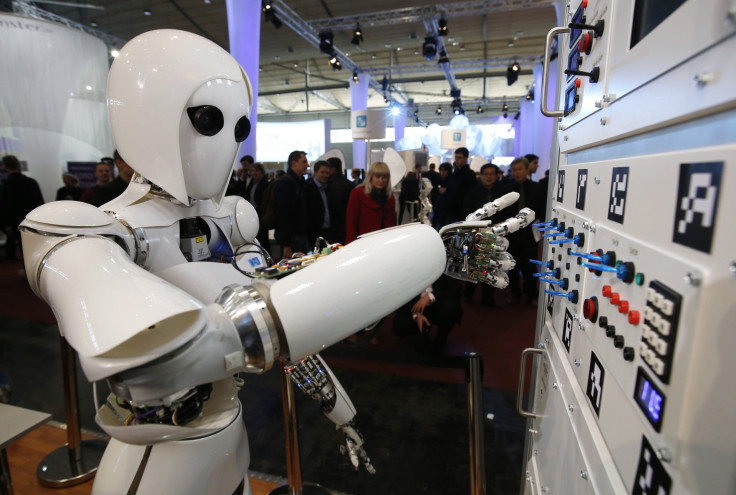

Still, while we can expect civilization to be relatively safe from autonomous robots, Americans’ jobs can’t say the same, according to the report. While it projected improved economic productivity for the U.S. following an embrace of AI, the NSTC warned of a likely negative impact on income inequality and wages in some sectors.

“Because AI has the potential to eliminate or drive down wages of some jobs, especially low- and medium-skill jobs, policy interventions will likely be needed to ensure that AI’s economic benefits are broadly shared and that inequality is diminished and not worsened as a consequence,” the report said.

And while there aren’t any Sci-Fi films involving a cyborg Schwarzenegger stealing regular folks’ jobs just yet, those fears aren’t unfounded.

In an October 2015 report, Darrell M. West, founding director of the Brookings Institution’s Center for Technology Innovation, noted that the total number of industrial robots in use around the world rose from 1.2 million to 1.5 million between 2013 and 2014. By 2017, he projects the total to hit 1.9 million.

“In a number of fields, technology is substituting for labor, and this has dramatic consequences for middle class jobs and incomes,” West wrote, pointing to many businesses’ decisions to replace human workers with automated ones as a means of cutting costs after the Great Recession. “One business leader I know had 500 workers for his $100 million business and now has the same size workforce even though the company has grown to $250 million in revenues. He did this by automating certain functions and using robots and advanced manufacturing techniques to operate the firm.”

An earlier, widely-cited study by Oxford University researchers Carl Frey and Michael Osborne estimated that the use of AI put 47 percent of total U.S. jobs at risk.

This would hardly be news to the city hosting the Frontiers Conference, where even Uber drivers have reason to fear AI edging them out of the workforce.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.