Going Big: How Stadiums Are Being Used In The Fight Against COVID-19

KEY POINTS

- The U.S. is far short of its vaccination goals

- President-elect Biden wants 100 million people vaccinated in his first 100 days

- Unlike the polio campaign in the 1950s, the effort is troubled by a trust deficit

Looking at the slow pace of providing inoculations against COVID-19, state and local leaders are starting to open up stadiums and other large facilities as mass vaccination sites, though guidelines on social distancing could complicate the effort.

President-elect Joe Biden, in an address to the nation on Thursday, said he aimed to have 100 million people injected with their first shots of the two-shot regime by the end of his first 100 days in office on April 30.

“This will be one of the most challenging operational efforts we have ever undertaken as a nation,” he said. “We will move Heaven and Earth to get more people vaccinated, to create more places for them to get vaccinated, to mobilize more medical teams to get shots in peoples’ arms, and to increase vaccine supply and get it out the door as fast as possible.”

To do this, Biden said, Congress needs to come up with $400 billion in funding, part of a broad-based $1.9 trillion stimulus package the president-elect is backing. The effort is needed, he said, because the vaccine rollout has “been a dismal failure thus far.”

Operation Warp Speed, a federal campaign to drive the vaccination effort, set a goal of having 20 million people inoculated with the first shot of either the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccine by December, and it fell well short.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the country's top infectious disease expert, said during the first week of January that any major program like a national vaccination campaign was sure to face hurdles early on. Injections have picked up from a snail’s pace to about a half-million a day, however.

“Once you get rolling and get some momentum, I think we can achieve 1 million a day or even more,” he told the Associated Press.

Many states are in various stages of a tiered vaccination campaign that puts the elderly and essential workers at the front of the line. With vaccination efforts gaining momentum, some states have moved to vaccinate adults 65 and older and other front-line workers not included in the initial stage.

The federal government advised coordination across state and local administrations in vaccine distribution, introducing a playbook in October for all 50 states and territories to consider when developing their individual plans.

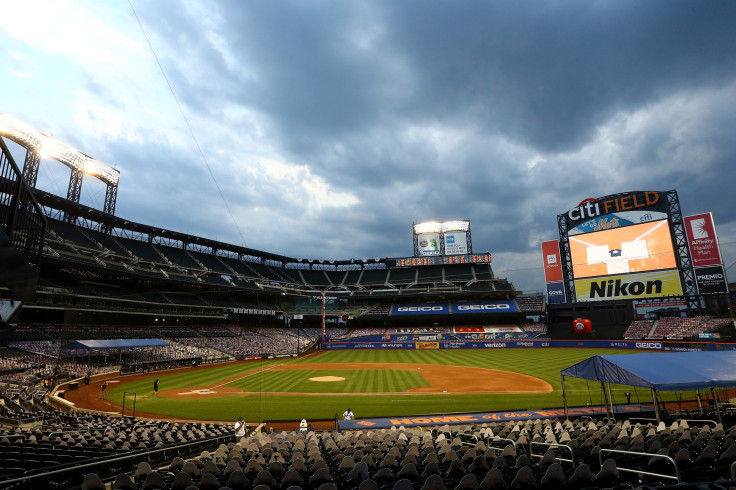

This week, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio said the city planned to open a mass distribution site in each of the five boroughs, part of an effort to get 1 million New Yorkers offered their first shot by the end of the month. Part of that plan includes opening up Citi Field in Queens, home to the New York Mets, as a 24-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week mass vaccination site with plans to inject at least 5,000 people per day.

“With a track record of testing millions of New Yorkers for the virus, the addition of our latest 24/7 vaccination site at Citi Field builds on the strong base we have established through the Test & Trace Corps to win the fight and finally end this pandemic,” said NYC Test & Trace Corps Executive Director Dr. Ted Long.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis got a bit of a head start on expanding vaccination sites in his state by opening Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, which is designed to host some 65,000 people for various events, for inoculations. The preliminary goal is to give out 1,000 shots per day.

Earlier this week, the Orlando Sentinel reported the owners of Disney World were in talks with Florida state officials on opening the Lake Buena Vista resort up as a mass vaccination center.

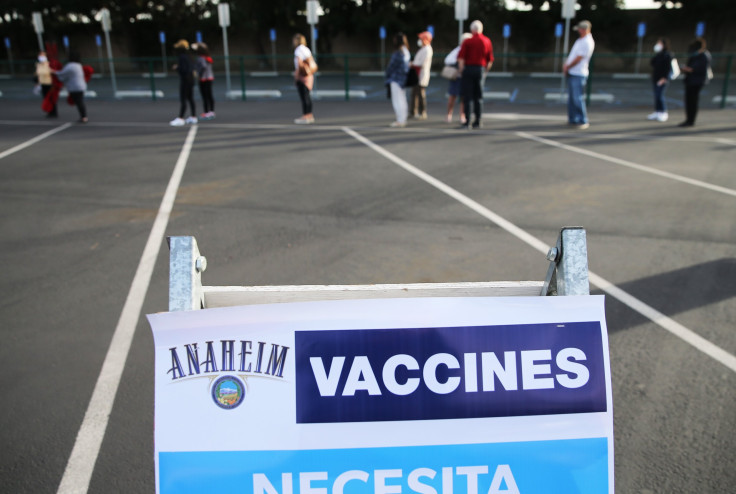

California is also getting in on the game. Andrew Do, the supervisor for Orange County in the state, said Wednesday that Disneyland had opened up as a “super point of distribution” site in Anaheim with the aim of vaccinating more than 7,000 Orange County residents a day.

“If given all the vaccines we need, our goal is to fully vaccinate all residents by July 4,” he tweeted.

And perhaps smaller in scale, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot on Thursday said the city would open college campuses up to serve as mass vaccination sites. Pacing about 38,000 doses per week, Lightfoot said it would take more than a year to vaccinate all the people in the city at the current rate.

As the vaccine rollout ramps us, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still advocates for social distancing, frequent hand washing, and the donning of a protective face covering to control the spread of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Shannon Kelley, a spokesperson for the Cleveland Clinic, said safety protocols should still be followed at distribution sites, big or small.

“While vaccinations will play a big role in slowing this pandemic, it’s important that we continue following public health precautions, including distancing, hand-washing, and masking, in daily life and at vaccine sites,” she told International Business Times.

Regardless of the size, the CDC recommends a reduction in crowd size and strict social distancing during any vaccination campaign. That means deploying signs, barriers, or other crowd-control methods, as well as using electronic communications as much as possible to avoid sharing things like pens and clipboards that, in theory, could spread the virus.

While setbacks in vaccination campaigns may be the ire of politicians, as Fauci explained, they are nothing new.

During the early stages of the polio outbreak, the government had a limited role in the public health response that left more than 3,000 people dead, mostly children, at its peak in 1952. President Franklin Roosevelt himself was left paralyzed by the disease at a young age.

Instead, the work was led by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, now known as the March of Dimes, which drew on grants to fund the vaccination campaign. The federal government had no distribution sites available when the first vaccines for polio were introduced, quarantines were largely voluntary, and places like movie theaters closed out of fear rather than government mandates. Any federal effort was geared mostly toward awareness. And instead of stadiums and arenas, patients queued up outside various medical clinics to receive doses. Polio was largely eradicated in the U.S. by the late 1970s.

Jeffrey Tucker, the editorial director for the American Institute for Economic Research, wrote an article comparing the COVID-19 vaccine campaign to the one for polio. Unlike the 1950s, when scientific achievements were lauded with a sense of national pride, Tucker said in an interview on Friday that there is an overwhelming amount of misinformation and general lack of trust that could complicate a mass vaccination campaign like the ones planned in New York, Florida, or California.

“There’s no question about the public’s wariness,” he told IBT. The messaging so far, he added, has been “absolutely chaotic.”

For President-elect Biden, he said, the trust deficit and the fear element need to be overcome.

Looking at the financial aspects of the vaccination efforts, analysts at Morningstar said Thursday the nation might not be out of the woods, even this year. “Using our estimates for virus transmission, the percentage of the population that has recovered from an infection, the efficacy of vaccination, and the speed of vaccine administration, we think herd immunity can be achieved in the U.S. by mid-2021 and globally by 2023,” they wrote.

As of Friday, the CDC estimated that of the 31.1 million doses of the various vaccines for COVID-19 in distribution, some 12.2 million were distributed as first shots in a two-shot vaccination protocol. An estimated 1.6 million people have received their second dose.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.