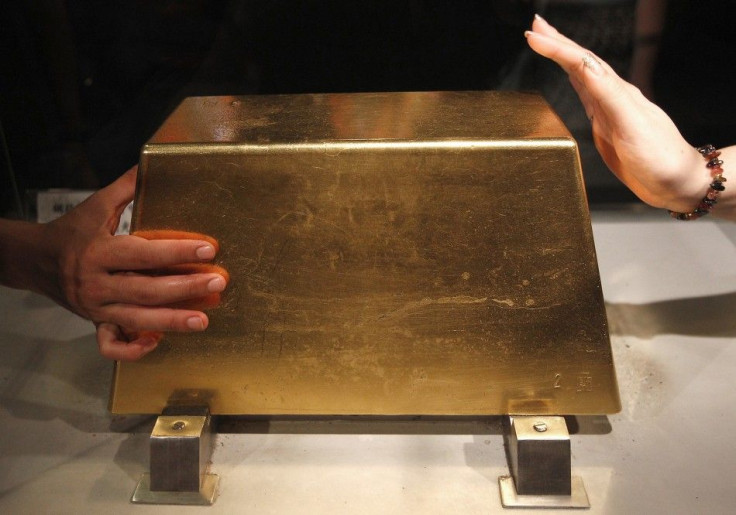

Gold in Review: How it Fared in 2011

Gold extended its record bull run in 2011 for an 11th year as confidence in the world's financial leaders and their stewardship of fiat currencies plummeted.

At the start of 2011 gold carried a spot price of $1,432.10 per troy ounce. By Sept. 6 it was worth $1,923, a 34 percent increase and a nominal record (though on an inflation-adjusted basis not close to the high of 1980).

Subsequent to reaching its new high, prices fell, tumbling particularly hard during September and again in December. Gold closed out 2011 with a more-than 10 percent gain on the year as it hugged its 200-day moving average.

In the first quarter, global gold demand rose 100 metric tons or 11 percent year-on-year to 981.3 metric tons worth $43.7 billion, according to the World Gold Council. Much of the increase stemmed from rising investor interest in bars and coins.

In the second quarter global gold demand was 919.8 tons, down from the year-earlier level, worth $44.5 billion, up from the dollar amount in the second quarter of 2010. Healthy growth in jewelry demand and modest gains in demand from the technology sector were offset by a year-on-year decline in investment, particularly in exchange-traded funds and similar products, the council said.

In the third quarter gold demand was up 6 percent to 1,053.9 tons worth a record $5.77 billion. The council credited a strong rise in investment demand that offset a decline in jewelry demand. The technology sector's demand for gold was steady.

Figures for the fourth quarter were not available from the council at the time this article was written.

Overall, the year's increase in gold's value stemmed from a loss of confidence in the world's financial leaders, particularly those in the Eurozone and the United States, and their responsibility for ballooning sovereign debt. Early in 2011 Greece's national debt climbed to about 200 percent of its gross domestic product. Late in the year the U.S. national debt blew past the 100 percent of GDP.

While the U.S. central bank can print money to inflate away some of its sovereign debt, Eurozone politicians who had spent years borrowing to pay for entitlements were not so lucky. By the fall of 2011, Greece had to pay more than 20 percent to borrow money for 10 years. It was a burden Athens had no way of carrying.

That forced the European Union to scramble for ways to keep Greece from defaulting. Eventually, a series of aid packages were arranged on condition that Athens impose severe austerity on the nation. Greek lawmakers accepted that condition for rescue money but riots marred the process.

Despite Greece not formally defaulting, Eurozone leaders pressured the continent's largest banks to accept a 50 percent loss of principle on their Greek government bonds -- in effect a de facto default and a finger in the eye of investors who were counter parties to credit default swaps on those government bonds.

In addition to Greece, Portugal and Ireland also required European Union bailouts for similar reasons.

No sooner had these four nations -- collectively called PIGS in a reference to their initials - been rescued than the crisis deepened dramatically: Italy, the Eurozone's third-largest economy, began having to pay record-high interest rates to borrow. Shortly thereafter Spain found itself in the same boat, as global bond investors, also known as bond vigilantes, began demanding huge yields to lend money.

Suddenly the Eurozone was forced to confront the possibility that the single currency would not long be the tie that binds the 17 Eurozone nations. That dawning was a driving force behind gold's record ascent this year, especially in the third quarter.

It was also the reason why big European banks found themselves facing a liquidity crisis. The effect of holding so much dicey debt from nations on the southern fringe of the Eurozone was an increasingly unwillingness by those banks to lend to one another. There were -- and are still -- reasonable grounds for worries about repayment. Prospects of a Lehman Brothers-style freeze looked more and more plausible. Eventually the European Central Bank was forced to offer 523 banks approximately $640 billion in 1 percent loans due in three years.

Near the end of December the ECB summarized the year's problems in a document that began as follows,

Risks to euro area financial stability increased considerably in the second half of 2011, as the sovereign risk crisis and its interplay with the banking sector worsened in an environment of weakening macroeconomic growth prospects. Indeed, several key risks identified in the June 2011 Financial Stability Review materialized after its finalization. Most notably, contagion effects in larger euro area sovereigns gathered strength amid rising headwinds from the interplay between the vulnerability of public finances and the financial sector. Euro area bank funding pressures, while contained by timely central bank action, increased markedly in specific market segments, particularly for unsecured term funding and U.S. dollar funding.

The Eurozone's liquidity crisis led to the dollar replacing gold as a safe haven as investors unloaded gold to raise badly needed cash.

The Eurozone's sovereign debt crisis did not only blew up the credit ratings of several member states, it blew up the careers of seven European heads of state -- Finland, Portugal, Denmark, Slovakia, Greece, Italy and Spain -- all of whom were casualties of the Eurozone's sovereign debt crisis.

As the crisis intensified and deepened Europe's leaders held a series of public meetings dubbed summits, in none of which was much accomplished to stop the contagion.

Contempt for the Eurozone's de facto capitol, Brussels, reached new heights. The Financial Times reported in December that anti-Brussels sentiment is at its highest in a generation.

Here's how the Wall Street Journal characterized the poorly regarded leadership of Europe: In 2011, European leaders have been unswerving in their commitment to muddling through.

The effect of years of irresponsible borrowing on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean emerged in somewhat less dramatic but no less consequential fashion in 2011.

U.S. economy's flickering recovery refused to be extinguished and towards the end of the year was showing staying power, thanks largely to the consumer. Corporate balances strengthened, and corporate default rates declined.

The year will be remembered as the beginning of a deflationary cycle, Dave Rosenberg, chief economist for Gluskin Sheff + Assoc. Inc. and formerly chief economist for Merrill Lynch.

The problem remains one of excess capacity across a wide gamut -- too much debt, too many vacant homes and an abundance of unemployed workers, he wrote at yearend. The U.S. output gap -- the difference between today's economic level of activity and the level that would be consistent with an economy operating at full capacity -- has never been as wide as it is currently. This gap between aggregate supply and demand will compound existing disinflationary pressures and ensure interest rates remain extremely low for an extended period of time.

Meanwhile the U.S. stock market ended the year flat, the first time it failed to rally in the third year of a presidential cycle in more than 70 years.

Whether in Europe or the United States, one of the chief beneficiaries of the year's stress over sovereign debt was gold.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.