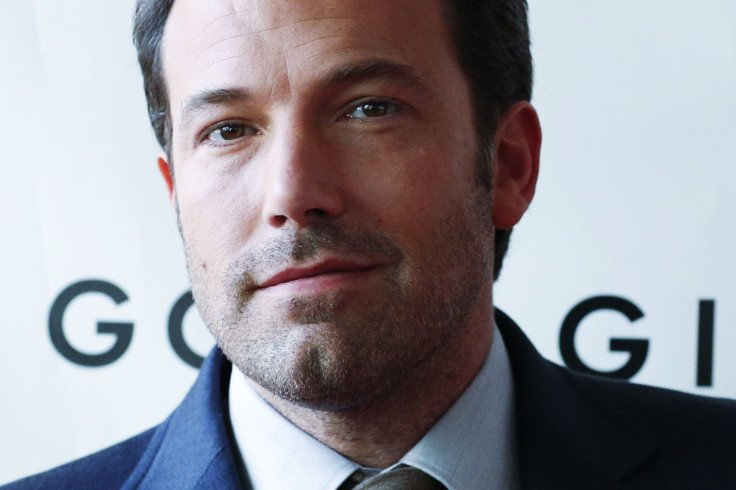

'Gone Girl' Movie Review: Ben Affleck Tries To Go Home Again In David Fincher's Creepy Cautionary Tale

“Gone Girl” has arrived, and it was worth the wait. David Fincher’s adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s best-selling thriller opened the New York Film Festival Friday night amid great expectations. And, for the most part, those expectations were met.

Amy Elliot Dunne (Rosamund Pike) is a picture-perfect girl who was never quite perfect enough. She grew up in the shadow of a fictionalized version of herself: Her child psychologist parents made a fortune on their children’s book series “Amazing Amy,” which the real Amy tells us functioned as an improvement upon her life and achievements. After Amy Elliot quit the cello at age 10, “Amazing Amy” became a prodigy. When Amy was cut from the volleyball team her freshman year, “Amazing Amy” made varsity. But in the eyes of Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck), a charming, Midwest-born, men’s magazine writer, the real-life Amy is perfectly amazing herself. Until she’s not.

Mr. and Mrs. Dunne’s charmed New York City life is a victim of the 2008 recession: First Nick and then Amy lose their magazine jobs, which is less of a catastrophe than it could be, thanks to Amy’s trust fund. But when that too is (mostly) lost and Nick learns his mother has stage 4 breast cancer, the not-so-newlyweds pack up and move to his hometown of North Carthage, Mo., where Nick can play the hero to his beloved mother and his twin sister Margo Dunne (Carrie Coon), and rewrite his crushing failures for a captive audience of townies who usher him in like the Homecoming King he (probably) once was.

Nick and Amy tell themselves and each other it’s temporary, but, since there’s nothing to go back to, neither of them believe it -- certainly not after Nick uses the last of Amy’s trust fund to open a bar (called “The Bar”) with Margo. There and only there, Nick can truly be himself: A clever, vaguely bitter, less vaguely lazy and dishonest man who would quite prefer that people wouldn’t expect too much from him. Especially his wife, who is increasingly bored and neglected in their rented McMansion, increasingly unable to maintain the laid-back, “cool girl” facade she believes won Nick over in the first place. In reality, Amy is not that cool. She wants what everyone wants, what she always wanted not to want.

When she disappears on the morning of their fifth anniversary -- the same morning that Nick reveals to Margo that all is not well -- Nick does not respond as a concerned, or innocent, husband should. He lies to the police, smiles for the cameras and visits with his too-young, too-willing mistress. The bored and struggling citizens of recession-torn North Carthage gorge themselves on the made-for-TV maybe-murder mystery, with the cloud of suspicion hanging over the prodigal son growing ever thicker. Amy herself is an agent of the investigation, having left a trail of clues for Nick before her disappearance that will lead to his anniversary present. This is a ritual Amy has performed every year, and one that Nick dreads, as every year it exposes his indifference to, and his cluelessness about, the little intimacies and inside jokes of their marriage that Amy so cherishes.

“Gone Girl” is a tale so creepy and absurd that it sometimes borders on farce, but Flynn and Fincher tie it down with threads of recognizable humanity. Indeed, “Gone Girl” is overstuffed with allegory, a cautionary tale about marrying outside your station, about exploiting romantic love as a warped mirror to the self, about how incompatible trying to appear like a good person and actually being one often are. Because Amy, for all her pathologies, is the truly dazzling one, the one who everyone looks at first, Nick is always measured against her. The more sympathetic Amy appears, the worse Nick comes off -- and vice versa.

It would have been a mistake for anyone but Flynn herself to tackle the screenplay. The author undoubtedly had visions of the silver screen dancing in her head when she first published the novel, which begged for a star-studded adaptation, but that does not mean there were not some hurdles to overcome. Flynn was up for the challenge: Critical scenes from the book are masterfully combined and condensed, and, although the backstory does not unfold exactly as it does in the novel, details key to understanding the characters’ relationships eventually make their way into the story.

Still, there could have been more offered to texture the marriage’s unraveling. For those who have not read the book, it may feel as though Amy and Nick turned on each other too abruptly. In an early scene in their Brooklyn brownstone, after they have both lost their jobs and Amy has paid her parents back most of her trust fund, the couple is convincing when they agree that, as long as they have each other, everything else is background noise. But before we understand exactly how and why, the proverbial knives are out, and all we can see and hear are the sharp edges.

As he showed us in “The Social Network,” Fincher can’t resist the occasional wink. Some are in the casting: Neil Patrick Harris’ first speaking scene as Amy’s former lover and semistalker appears intended to amuse (and it did so for a packed audience at a screening Friday). And some of the more horrific stuff, which can’t be spoiled, is presented as an artful and comedic homage to a style far less curated and controlled than Fincher’s.

In the end, control is what “Gone Girl” is all about. But we should have known that from the beginning.

“Gone Girl” is currently screening at the New York Film Festival, and opens in wide release Oct. 3. Directed by David Fincher. Screenplay by Gillian Flynn. Starring Ben Affleck, Rosamund Pike, Neil Patrick Harris, Tyler Perry. From 20th Century Fox.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.