With Google’s Support, Plant Biologists Build First Online Database Of All The World’s Plant Species

Wayt Thomas carefully opens a manila folder, the contents of which he has been pondering for months. Tucked within it is a yellowing, dried-out blade from a plant that looks a lot like grass to an amateur eye. But it’s not a grass, it’s definitely a sedge, he says – the stem is triangular and the blades or leaves stick out at a 120 degree angle, instead of the 180 degrees typical of grasses. The blades are also serrated and rough to the touch – not smooth, like many grasses.

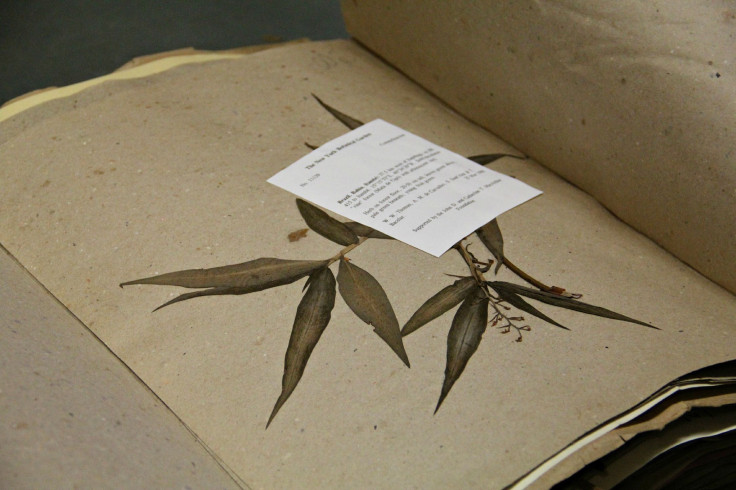

As an expert in the flora of the tropics of North and South America at the New York Botanical Garden, Thomas is fairly certain that the plant in the folder in front of him is a brand new species. The tufts of seed called spikelets at the ends of the plant’s slim stalk are what tipped him off. “All the spikelets are completely separate and in other species, they’re all grouped together,” he says. But it’s hard to be sure that no other scientist in the world has never described this specimen, which was originally mailed to him from Ilheus, Brazil, in 1996.

When plant biologists and field researchers come across a species they’ve never seen before, they turn to thick encyclopedia-like volumes called monographs with titles such as Flora Braseliensis that characterize each species in a region in great detail. But not every species has been well-described in this literature. Thomas estimates that only 10 percent of species in the American tropics have been properly characterized. And the reference materials that do exist sometimes don’t match, or are inaccessible to anyone who doesn’t have access through a university.

Four of the world’s leading botanical gardens would like to change that. Since 2012, they have been working toward building a free online database called World Flora Online of the world’s plant species – all 350,000 of them – so that scientists can more easily identify plants and share information about them. Thomas calls it “the WebMD” for plant biology. With a fresh new round of funding this spring including a $1.2 million grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and a $600,000 commitment from Google accompanied by a pledge to provide cloud storage for the project, the consortium has expanded to include 35 affiliates from around the world.

“Plants are hugely, hugely important for us,” says Doron Weber, vice president at the Sloan Foundation. “Plant research is very promising -- it's necessary for food, for medicines, for various materials. It's also the basis of healthy ecosystems and habitats. You can be completely bottom line about this.”

Once complete, field plant biologists will no longer have to scour the Internet for obscure reference material – Thomas says it will all be right there in World Flora Online. The peer-reviewed database should also allow researchers to study the distribution and conservation status of hundreds of thousands of species at once, and layer it against data on climate or soil type.

"It's worthy, it highlights the importance of plants," William Crepet, chair of the department of plant biology at Cornell University, says. "We anticipate global needs associated with population growth and climate change and we feel plant science is important in addressing those needs."

One of the first tasks for researchers involved in the project is to set the bounds for each plant species – currently, records from different areas of the world do not match up and a single species may be referred to by several different names. Specialists at the botanical gardens involved in World Flora Online – which include the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh in the U.K. and the New York Botanical Garden and Missouri Botanical Garden in the U.S. – are carefully debating each entry on a master “plant list” of all species that will be identified in the database.

Meanwhile, the New York Botanical Garden has dedicated its first researchers and a team of digitization experts to lay the groundwork for the system. Melissa Tulig leads the information team at the herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden. Her task is to covert a 110-volume set of heavy and expensive monographs published by the New York Botanical Garden Press into a searchable online database.

“Most of the current information, you can't readily get to -- especially if you're from a developing country,” Tulig says. "That's what we're trying to fix." Right now, the books are only available to researchers at universities or through JSTOR, an online database that requires a subscription fee.

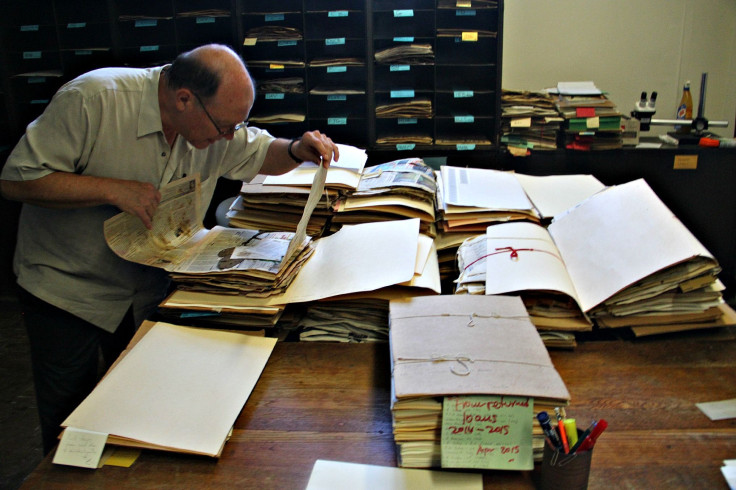

Thomas appreciates the magnitude of the task of bringing the world’s plant species online because he can barely keep up with the stacks of manila folders filled with potentially new species on his desk. Never mind that there is a large metal file cabinet next to his office filled with more samples. In fact, each specialist at the Garden has four or five cabinets with his or her name scrawled across the front, filled with samples waiting to be reviewed.

And that’s only the start. Downstairs, a chamber called the “cold room” is lined with roughly 100,000 plant specimens in stacks of manila folders tied together with twine. All these samples have been mailed to the Garden over the years and are just waiting for a specialist to take a look. They are arranged on shelves in accordance with which plant group they belong to. Handwritten labels denote the date on which they were first received – as early as the 1980s in some cases.

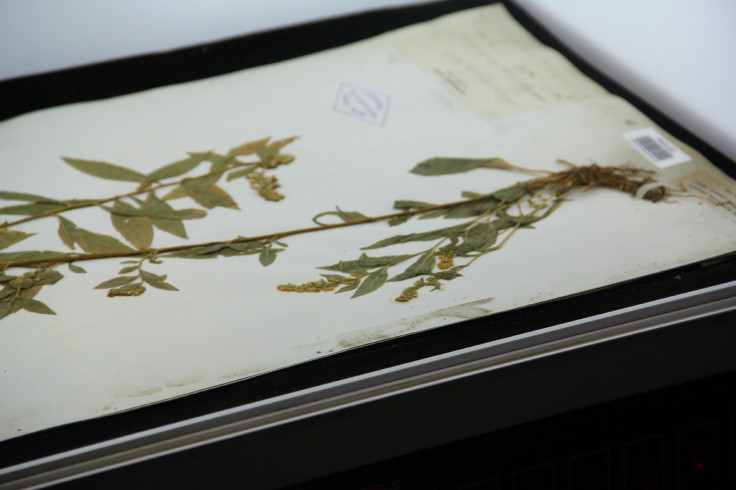

Many of these specimens are eventually identified. Once a specialist determines the proper name for a sample, it is sent off to a mounting room to be delicately glued or – for samples with thick bark that won’t adhere easily – carefully sewn onto a piece of thick paper.

Then, the mounted samples are placed back in manila folders and transferred to a small staff of imaging experts. This team uses a converted lightbox originally intended to take close-ups of rings and necklaces for online jewelry sellers to snap a photo of the specimen. Next, the samples go to the herbarium where they are filed alongside other members of their genus.

The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden is filled with 7.4 million samples, including many repeats of the same species. Some are from Captain Cook’s original voyages in the late 1700s. Others are designated as “type specimens,” which means that their characteristics have been used to write the textbook definition for an entire species. Tulig says each of these records will eventually be uploaded to World Flora Online.

But converting more than a hundred monographs and millions of herbarium records to a digital database is no easy task. The oldest monographs printed in the 1960s and 1970s were produced on a typewriter, so there is no original digital file for Tulig's team to refer back to. The group must also assign metadata such as keywords and tags to each entry that matches the metadata entered by other botanical gardens, which are uploading their own records.

Thomas says the recent contributions from Google and the Sloan Foundation have given the team a running start, but he says the New York Botanical Garden still needs over $2 million to do the basic work of digitizing their data, and will continue to raise money to add additional features after the database is live. The other three major partners are also fundraising about the same amount, and seeking a total of roughly $8 million for the project. The consortium has a stated goal of launching the first version of World Flora Online in 2020.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.