Gov. Christie Shifted Pension Cash to Wall Street, Costing New Jersey Taxpayers $3.8 Billion

Gov. Chris Christie's administration openly acknowledged that more New Jersey taxpayer dollars were going to land in the coffers of major financial institutions. It was 2010, and Christie had just installed a longtime private equity executive, Robert Grady, to manage the state's pension money. Grady promoted a plan to put more of those funds into riskier investments managed by Wall Street firms. Though this would entail higher fees, Grady said the strategy would "maximize returns while appropriately managing risk."

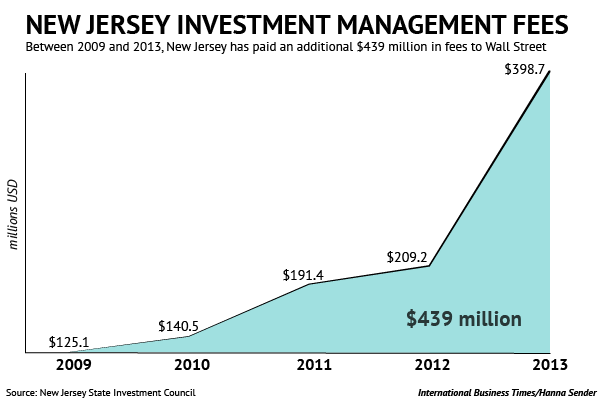

Four years later, New Jersey has secured only half the promised results. The state has sent more pension money to big-name Wall Street firms like Blackstone, Third Point, Omega Advisors, Elliott Associates and Grady's old firm, The Carlyle Group. Additionally, the amount of fees the state pays financial managers has more than tripled since Christie assumed office. New Jersey is now one of America’s largest investors in hedge funds.

The “maximized returns” have yet to materialize.

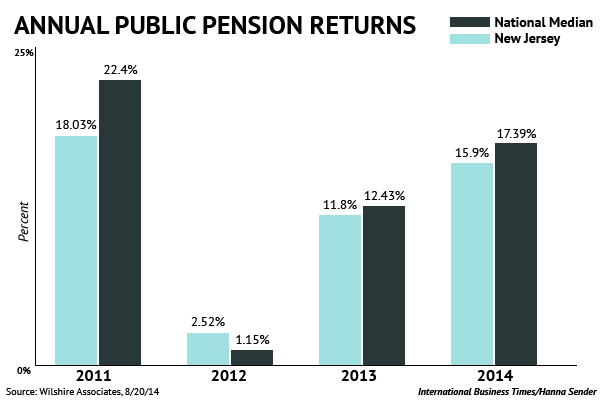

Between fiscal year 2011 and 2014, the state’s pension trailed the median returns for similarly sized public pension systems throughout the country, according to data from the financial analysis firm, Wilshire Associates. That below-median performance has cost New Jersey taxpayers billions in unrealized gains and has left the pension system on shaky ground. Meanwhile, New Jersey is now paying a quarter-billion dollars in additional annual fees to Wall Street firms -- many of whose employees have financially supported Republican groups backing Christie’s reelection campaign.

Those who originally opposed the state's shifting of pension funds into hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, real estate and other “alternative investments” see the below-average returns as no accident but an inevitable byproduct of the strategy: The Christie administration has effectively taken money from retired state workers and delivered the cash to Wall Street money managers.

“All the leading players on the [New Jersey State Investment Council] were from the alternative universe and all of their decisions were driven by a political agenda and an investment ideology which had no relationship to facts on the ground. And the facts were that you simply couldn’t justify these investments on the basis of what they cost in fees to generate a dollar of new returns,” Jim Marketti, one of the few State Investment Council members to vote against the Christie administration’s transfer of pension money into alternative investments, told International Business Times. In 2011, Marketti warned the council that such investments would be “a roller coaster ride on which only the Wall Street professionals and insiders are the winners.”

Grady and Christie did not respond to IBTimes' requests for comment about the higher fees and below-median returns. A spokesman for New Jersey State Treasurer Andrew Sidamon-Eristoff said New Jersey “has produced positive returns for Fiscal Year 2014 of 15.9 percent” but declined to answer questions about how those returns -- and others from previous years -- trail the median for pension funds throughout the country. He also refused to answer questions about the state paying higher fees to Wall Street firms.

In 2009, the year before Christie took office, New Jersey spent $125.1 million on financial management fees. In 2013, the most recent year for which data is available, the state reported spending $398.7 million on such fees. In all, New Jersey’s pension system has spent $939.8 million on financial fees between fiscal year 2010 and 2013. That’s only a little less than the amount Christie cut from state education funding in 2010 -- a cut that played a major role in shrinking the state’s teaching force by 4,500 teachers. That money might also have reduced the amount the state needs to pay into the pension system to keep it solvent.

Higher management fees are supposed to buy -- and therefore be offset by -- better investment performance for pension funds, but New Jersey’s pension investment performance has fallen far behind other states'. That’s likely a combination of below-market returns and the Wall Street fees the pension system wouldn’t have paid if it had followed the states that put less money in alternatives and more in stocks, index funds, bonds and other low-fee investments.

New Jersey’s high-fee, low-return results illustrate a larger trend. In authorizing its pension system to hand over more than a third of its $80 billion portfolio to private equity, hedge fund, venture capital and real estate firms, the state is one of many that has shifted more public money into alternative investments. The National Association of Retirement Administrators estimates that pension systems have tripled such holdings in the last dozen years, with the average system now having nearly a quarter of its funds in alternatives. And data from across the country show that shift has often been accompanied by similarly below-average returns, exacerbating pension shortfalls.

New Jersey’s pension fund is currently $47.2 billion short of what it needs to fulfill benefit promises to retirees. Christie has been defending his May decision to skip this year’s required payment to keep up with pension obligations, thereby increasing the gap between the system’s assets and its liabilities. As justification for the move, the governor has argued that retirement benefits for New Jersey police officers, firefighters and teachers are unaffordable and therefore must be reduced.

Christie and his appointees defend their investment strategy by contending that recent returns justify the higher fees. "The return on investment this year for the pension fund is 12.9 percent, nearly 5 points above the assumed rate of investment," Christie told a radio caller critical of the state's pension investment strategy. He said the state's investments have "overperformed" and been "outstanding." "There are certain things you can complain about about state government, but [investment returns] ain't one of them," he said.

That kind of rhetoric has succeeded in shaping the political narrative, and it is true that returns this year have been better than those projected by Christie officials. But this year and over the last four years as a whole, the returns have been below the median for similarly sized public pension systems throughout the country.

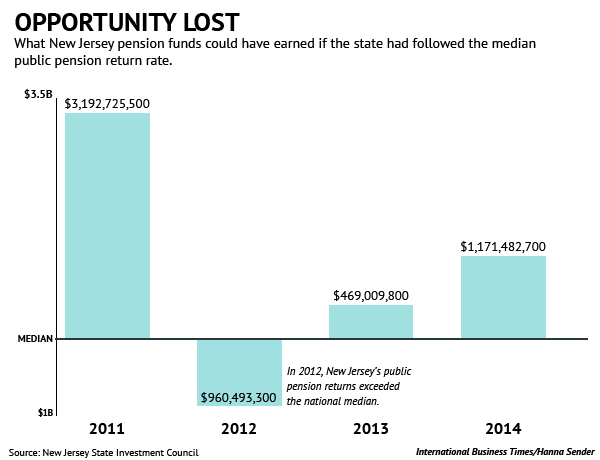

Had New Jersey’s pension system simply matched the median rate of return, the state would have reaped roughly $3.8 billion more than it did between fiscal years 2011 and 2014, says pension consultant Chris Tobe. Those unrealized gains represent more than New Jersey’s annual budget for its entire higher education system, and more than 10 times what the state spends each year on environmental protection. It is also more than enough to cover the required pension payment that Christie cut. To make up for that $3.8 billion return-on-investment gap, every household in the state would have to cough up roughly $1,200.

Tobe says about $1 billion of the $3.8 billion billion gap can be attributed to the higher Wall Street fees that eat into pension returns -- an estimate that roughly tracks New Jersey State Investment Council documents showing $939.8 million in financial management fees since Christie took office.

“We certainly cannot afford to pay higher fees for below-average returns,” said Wendell Steinhauer, president of the New Jersey Education Association, the union representing teachers whose pensions are on the line. “That doesn’t just hurt people in the pension systems; it hurts every New Jersey taxpayer.”

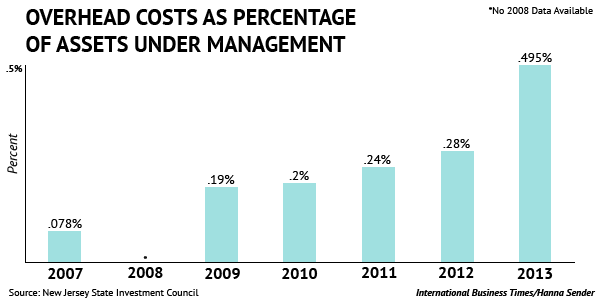

Christie officials have periodically boasted about their efforts to negotiate fee reductions with specific firms. But in fact the total overhead costs of managing New Jersey’s pension system -- including fees and administrative costs -- have jumped. New Jersey financial records show that in 2009 pension management costs were 19 cents for every $100 of money in the pension fund; in 2013 those costs were almost 50 cents per $100, according to state documents. For comparison, a joint study of 2012 data by the Maryland Public Policy Institute and the Maryland Tax Education Foundation found that the median rate of overhead costs for state pension funds is 39 cents per $100 under management.

The above-average costs for New Jersey are a direct result of Christie administration officials moving more pension money to Wall Street firms. The management fees those firms charge are far more expensive than the fees for passive index funds and the costs associated with equities being managed by in-house pension staff. Investments with Wall Street managers comprise less than half of New Jersey's pension portfolio -- but those investments’ attendant fees account for 96 percent of the pension system’s total overhead expenses, according to State Investment Council documents.

Billionaire investor Warren Buffett advised San Francisco pension officials in May to avoid alternative investments such as hedge funds. But Orin Kramer, a hedge fund manager who preceded Grady as chairman of the State Investment Council, told IBTimes that New Jersey’s move into alternative investments was necessary to diversify the state’s portfolio and protect against stock market volatility. He suggested that the strategy needs to be given more time to show its full results.

“Assuming you have an intelligent portfolio mix, over a 3 to 5-year period, stupid people can look really good and smart people can look really stupid,” he said. “Over any four-year period, the very best managers and strategies will look bad and managers and investment strategies you should find scary can look terrific. And obviously alternative investments have higher fees than managing pension money internally. But that’s the political risk you take.”

In a 2013 interview with a financial trade magazine about his push for more alternative investments, Grady criticized other pension systems’ problems with "pay-to-play or people who knew board members getting allocations." He said he aimed "to protect the staff from political influence." But as Grady's strategy has generated ever-higher fees for Wall Street firms, many executives of those firms have poured money into groups supporting New Jersey Republicans.

As previously reported by IBTimes, campaign finance records show that employees and others affiliated with firms managing New Jersey pension money made $167,000 worth of donations to New Jersey Republicans since 2009. Employees of those firms have also donated more than $11 million to the Republican Governors Association and the Republican National Committee. Christie is the chairman of the RGA and both organizations spent heavily to support his 2013 reelection campaign.

Despite federal and state pay-to-play rules restricting campaign contributions from employees of firms doing business with public pension funds, many of the donations were made around the time that pension investment contracts were awarded by Grady's State Investment Council. At least one of those contracts went to a venture capital firm after one of the firm’s partners made a $10,000 contribution to the New Jersey Republican Party. That sequence of transactions is now under investigation by New Jersey officials.

As IBTimes also reported last week, at the time many of those campaign contributions were made, Grady was not only changing New Jersey's portfolio in ways that benefited many of the donor firms, he was also in close contact with Christie campaign fundraisers. Grady, a former managing director of the Carlyle Group, still maintains an ownership stake in private equity funds managed by Carlyle, according to New Jersey financial disclosure documents. That firm and its subsidiary received $450 million worth of New Jersey pension investments since Christie took office. Carlyle is one of the top fee generators on Wall Street.

Grady recused himself from the final votes on those Carlyle investments, and he told IBTimes that pension business was not discussed during his communication with Christie’s campaign.

As Christie continues campaigning for a new round of pension benefit cuts, and as more pension money flows to Wall Street, Pat Provnick, a retired educator from Camden County, said retired teachers, firefighters and police officers no longer trust that the pension fund is being managed with their best interests in mind.

“Retirees are terrified,” she told IBTimes. “When you elect people, you hope that they are going to do what’s in the best interest of the people they represent, not just what’s in the best interest of their political aspirations, and when you find out that they may be thinking only of their own interests, you lose faith in any of their decisions.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.