Grand Ayatollah Sistani, Iraq's 'Shepherd', To Meet Pope Francis

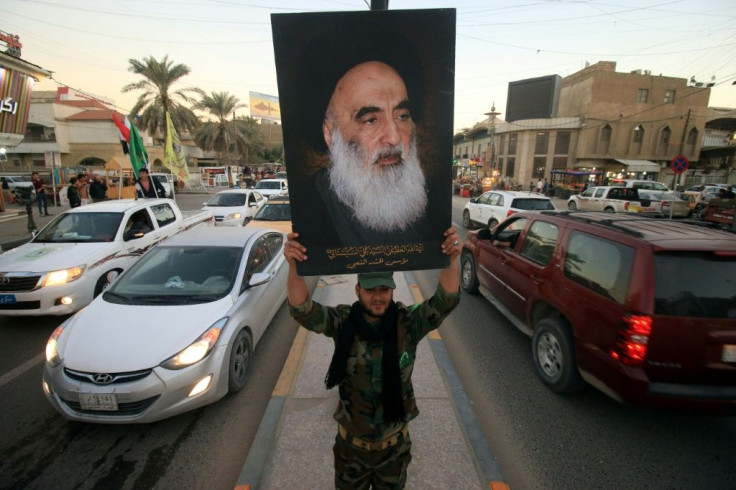

Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the highest religious authority for Iraq's Shiite Muslims, has wielded subtle but unprecedented power for a cleric, guiding his followers through decades of dictatorship, occupation and conflict.

The highly reclusive 90-year-old is set to meet the Catholic Church leader Pope Francis in the holy shrine city of Najaf on Saturday, during the first papal visit to Iraq.

It will be a rare in-person meeting for Sistani, whose sermons are typically delivered through a representative.

That has not dulled their effect: his words have sent thousands of Iraqis to polling stations, protest squares or battlefields since the US-led invasion in 2003.

"Despite a broad shift away from religion around the world, the reverence for Sistani is unmoved," said Marsin Alshamary, a Brookings Institute research fellow.

The thin, wispy-haired cleric has had to balance the conventional role of the revered establishment known as the "marjaiyah" with the expectation since 2003 that it would also have a political voice.

He did so carefully, departing from the apolitical legacy of the "marjaiyah" while trying to preserve it.

"Sistani is not a quietist, but he's not a revolutionary either," said Alshamary.

Sistani was born in the Iranian city of Mashhad in 1930 to a family of revered clerics and started his religious studies at the age of five, later moving to Iraq and ascending through the ranks of Shiite clergy to grand ayatollah in the 1990s.

Under Saddam Hussein's repressive regime, he languished under house arrest for years.

But after 2003, Sistani emerged from isolation to play an unprecedented public role while Iraq suffered a "vacuum for real leadership", said Alshamary.

The cleric firmly opposed the US-led occupation, insisted Iraq be swiftly granted full sovereignty and threw his weight behind elections, moulding a pan-Shiite coalition in the 2005 parliament.

Sistani was a voice for moderation, repeatedly calling for calm during Iraq's brutal sectarian conflict from 2006 to 2008 and even brokering ceasefires between warring parties.

In June 2014, he issued an historic edict calling on Iraqis to take up arms against the Sunni jihadists of the Islamic State group, who had swept across swathes of the north.

This spawned the creation of the Hashed al-Shaabi, a loose network of armed factions, many of them close to Iran, which now wields major political and military sway.

Throughout, Sistani also tirelessly advocated for high turnout in elections and criticised government graft.

In 2015, he told AFP in a written response to interview questions about his reform crusade that he had hoped elected officials could lead Iraq without his intervention.

"Unfortunately, things happened differently," he said.

When mass anti-government rallies erupted in 2019, he supported their demands and met often with the United Nations' top official in Iraq to set out a reform roadmap.

His call for parliament to drop support for then-prime minister Adel Abdel Mahdi prompted the PM's resignation.

Still, he faced criticism from protesters looking for a tougher line, and resistance from political actors.

Around the time the coronavirus pandemic first hit Iraq in the spring of 2020, Sistani went silent and stopped issuing weekly sermons.

Sistani has had a complicated relationship with his birthplace, Iran.

In the only known footage of him, he is seen speaking fluent Persian, but he has also been known for pushing back against Iran's growing clout.

That partly stems from the centuries-old rivalry between Najaf and Iran's Qom over which is the seat of Shiite religious authority.

"Sistani consistently kept Iran at arm's length, as he saw himself as a competitor to Qom and did not want to be dictated to by Iran," said Kenneth Katzman, an analyst at the US Congressional Research Service.

Sistani has reportedly twice declined offers of Iraqi citizenship, but is widely seen as a national symbol.

"Sistani has never denied that he's Iranian, yet in many ways he is more Iraqi than Iraq's own leaders," said Hayder al-Khoei, a researcher on Iraqi politics and Shiite religious affairs who met Sistani several times.

Another difference is over the role of religion in politics: while Iran is ruled by clerics, Sistani has always eschewed any formal role in government.

Alshamary said that could make him "wary" of signing on to the document on "human fraternity", an interfaith text condemning extremism, as Catholic clerics would like him to do.

Francis signed it with the leading Sunni cleric Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayeb, the grand imam of Al-Azhar in Cairo, in February 2019.

Francis and Sistani will meet for a "private visit" in Najaf, where Sistani lives in spartan surroundings.

Despite his humble appearance and his non-Iraqi roots, he is seen as an essential figure in Iraq's recent history.

"No one else will ever occupy a position like that," said Alshamary. "He shepherded Iraq through all these difficult times."

© Copyright AFP {{Year}}. All rights reserved.