A Great Lakes Pipeline Dispute Points To A Broader Energy Dilemma

A deal involving an aging oil pipeline in Michigan reflects the complex decisions communities across the country need to make to balance the needs for energy and safety with efforts to deal with climate change.

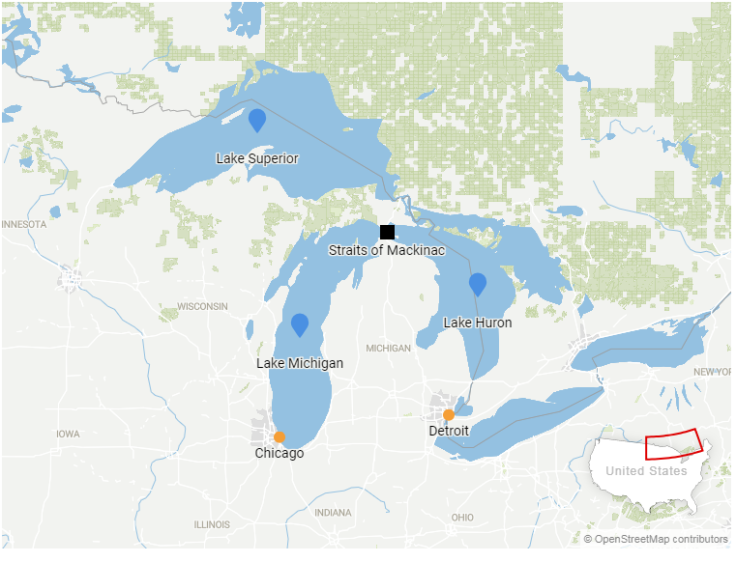

Gov. Rick Snyder and Enbridge, a Canadian company, have reached an agreement over a leak-prone pipeline that runs beneath the Straits of Mackinac, the 4-mile-long waterway that divides Lake Michigan and Lake Huron.

Rather than shut the 65-year-old pipeline down altogether, as environmentalists are demanding, or conduct routine maintenance, as Enbridge desired, Snyder is requiring Enbridge to replace the pipeline at an estimated cost of up to US$500 million without a deadline.

While the lakes, beaches and livelihoods vulnerable to harm from a potential spill are perhaps unique to Michigan, the question of what to do about a host of aging pipelines across the U.S. is not. Nearly half of the nation’s pipelines currently operating were built before 1960.

Amid rising oil and gas production, there are hard compromises to make between ensuring an adequate energy supply, protecting public safety, and reducing the nation’s reliance on fossil fuels – a key contributor to climate change. But my research suggests that there may be a straightforward way for both decision-makers and the public to make these choices.

Straits of Mackinac

Millions of miles

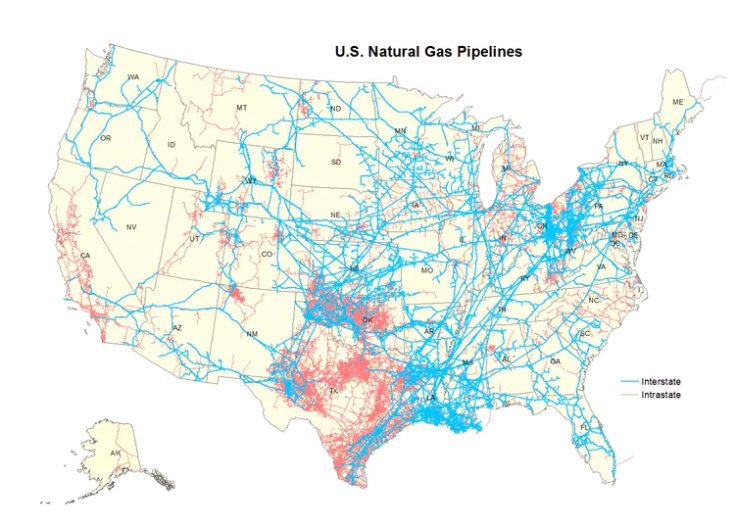

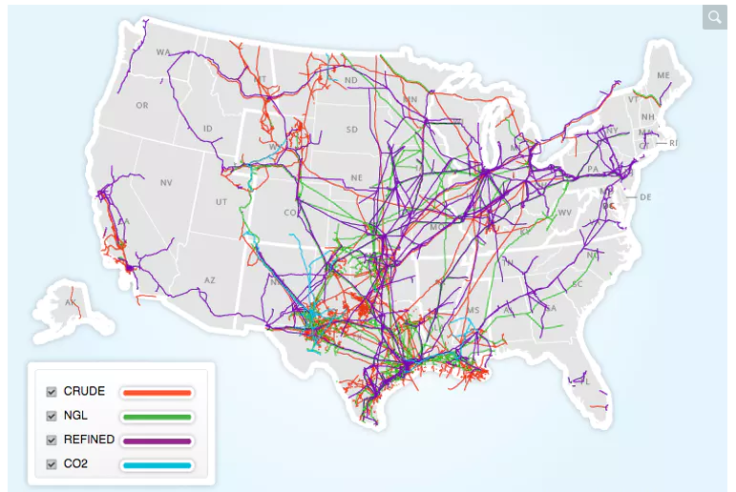

Approximately 3 million miles of pipelines move crude oil, natural gas and other hazardous liquids across the U.S. Most crude oil pipelines traversing the center of the country transport oil from western Canada and North Dakota southward to refineries in Texas and Louisiana.

Much of this system dates back to the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s. Indeed, roughly half of the crude oil pipelines operating today are at least 50 years old.

More of the natural gas pipelines that span the county are concentrated around the Marcellus Shale formation, in eastern Ohio and Pennsylvania. And 60 percent of the 319,000 miles of pipelines currently transporting natural gas were installed before 1970.

A recent Department of Energy report suggested that replacing just the cast-iron pipelines, which are the oldest and riskiest variety, would cost approximately $270 billion.

The risks

Compared to hauling fuel by rail or truck, the Transportation Research Board, a nonprofit that serves as an advisory body to the White House, Congress and federal agencies, considers pipelines to be safer. Yet when pipeline accidents do occur, they are typically larger and impact the environment more directly than the alternatives.

When a natural gas line exploded in Massachusetts, where many pipes are over 100 years old, it destroyed 80 homes and killed one person. In 2012, another pipeline operated by the same company – Columbia Gas, this one built in 1967, exploded.

That earlier accident in Sissonville, West Virginia, charred 800 feet of roadway along a nearby highway, wrecking three homes, and melted the siding on houses hundreds of feet away. Following an investigation, the National Transportation Safety Board found many causes. Among them: corrosion and a lack of automatic or remote shutoff valves.

In 2010, one of Enbridge’s Michigan pipelines ruptured, spilling 1 million gallons of oil into the Kalamazoo River. That pipeline was built in the 1960s, and made with the sorts of welding processes and protective coverings that have not stood the test of time. The cost to clean up that spill was more than $1 billion and spurred concerns among Michiganders over the safety of the Straits pipeline.

A big spill in the Straits of Mackinac could result in oil polluting over 1,200 miles of shoreline, cause $1.3 billion in damage and cost $500 million to clean up, Michigan Technological University researchers estimate.

Following an independent risk analysis, Snyder and Enbridge agreed that a replacement pipeline should be placed inside a tunnel and buried beneath the lakebed. Taking that step would substantially reduce the risk of a spill. But it will also take at least seven years to build. And the agreement assumes the Straits pipeline would continue to operate during the new pipeline’s construction.

Fracking boom

There’s one good reason why old and dangerous pipelines aren’t being shut down: the emergence of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking – the process by which water, sand and chemicals are injected underground at high pressures to crack rock and release the oil and gas trapped inside.

Despite concerns regarding methane leaks, water and air pollution and even earthquakes, there’s no sign that the fracking boom in oil and gas production over the next decade will slow.

The oil and gas industry anticipates production in places like North Dakota will keep growing over the next two decades.

According to the American Petroleum Institute, building the pipelines to accommodate this increase in output would require annual investments between $12-19 billion. A 2008 report prepared for the Edison Foundation predicted that modernizing the national oil and gas transmission and distribution network would cost $900 billion before 2030.

Some trade-offs

As the battles over the Keystone XL and the Dakota Access pipelines have shown, opposition to new long-term fossil fuel infrastructure projects is growing. Replacing old dangerous pipelines with new ones is not easy – or fast, even if it might reduce risks and carbon emissions.

There is also growing evidence, such as the latest report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that instead of a bigger and better pipeline network, the U.S. needs a new energy strategy, aimed at ending reliance on fossil fuels altogether by 2050. The problem is that once pipelines are built, they typically last decades. Building new ones would further lock in dependence on fossil fuels.

A recent poll shows that a majority of Americans support aggressive action on global warming. But smaller numbers back some of the specific policies or actions that might take.

As my research suggests, adopting a more comprehensive and logical process for making decisions could provide a way forward. This process helps communities identify their most important objectives first and then evaluate options according to those specific goals. It’s an approach that ensures that what’s most important – climate change, jobs and protecting ecosystems, for instance – gets addressed.

It could become handy the next time a state and a corporation tangle over whether or not to replace a big aging pipeline – even when this debate is less contentious than the one about Michigan’s Straits of Mackinac.

Douglas Bessette is an Assistant Professor of Community Sustainability, Michigan State University.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation. Read the original article here.